For the Odessa art world, the main event of 2015 was undoubtedly the “l’Enfant Terrible” exhibition which took place in the Kyiv National Ukrainian Museum of Art. Subsequently, the Odessa Museum of Modern Art conducted an enormous investigative effort to compile a hefty catalog before it subsequently hosted another iteration of the same exhibit.

Odessa has staked out its claim in the artistic sphere, giving birth to its own artistic movement. Thus we have ‘Odessa Conceptualism’, a home grown Odessan art movement imprinted with the values of the city. Of course, conceptualism as a current of contemporary art had already been present in the western world since the early 60’s, – but the unfortunate denizens of the USSR were obviously unaware of its existence (though to be fair they were also unaware of many other cultural phenomena). The country was trapped behind the iron curtain which allowed for no outside cultural penetration. Thus, when we hear the local artists’ claims to having had “invented” conceptualism – this is certainly not an empty boast. They did not have and could not have had any idea of its Western existence, and so they reinvented the wheel.

The movement was born as a response to the ubiquitous slogans and commands which permeated Soviet society

Moreover, owing to their activity, Odessa’s contribution is now known not only in places like Berlin, but is also recognized even in Moscow – the home of all the varied post -Soviet forms of conceptualism.

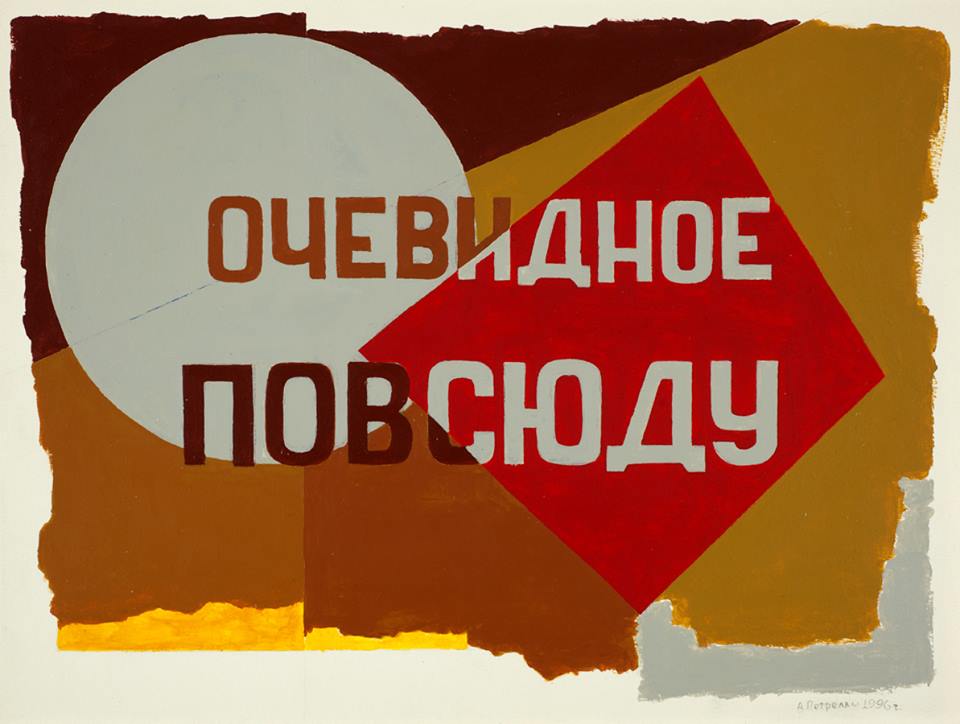

The movement was born as a response to the ubiquitous slogans and commands which permeated Soviet society; conceptualism was a direct answer to the absurd (and often plainly idiotic) Soviet mantras. It strove to use the Soviet authorities own semiotics against them. The conceptualists took real phrases, newspaper headings, and slogans and turned them into something completely antithetical to the officially intended meanings, taking the Soviet rhetoric to its logically absurd conclusion. These young people (who only later would assume the title of “artists”), in fact these Enfants Terribles, simply gathered in makeshift underground “salons” to party, exchange sarcastic jokes, to have dark acerbic fun at the expense of the thoroughly rotten late-Communist ideology. They were trying to come up with ways to humiliate it, to “get one over” on it, without the system becomingaware and punishing them for it.

They were not part of the official artistic milieu, and that is the reason that textual works dominated the early movement. They were not quite dissidents however. Their political discontent was expressed through an exhibitionism of everyday late-Soviet norms and standards, and the wry assault against the system’s hypocrisy and absurdity percolated underground.

Why Odessa specifically? Most likely this is because of the town’s proximity to the sea. Port cities always foster cultural exchange even when they are located in reclusive regimes, and this in turn makes for an irreverent insubordination against imperial – or faux-imperial – control.

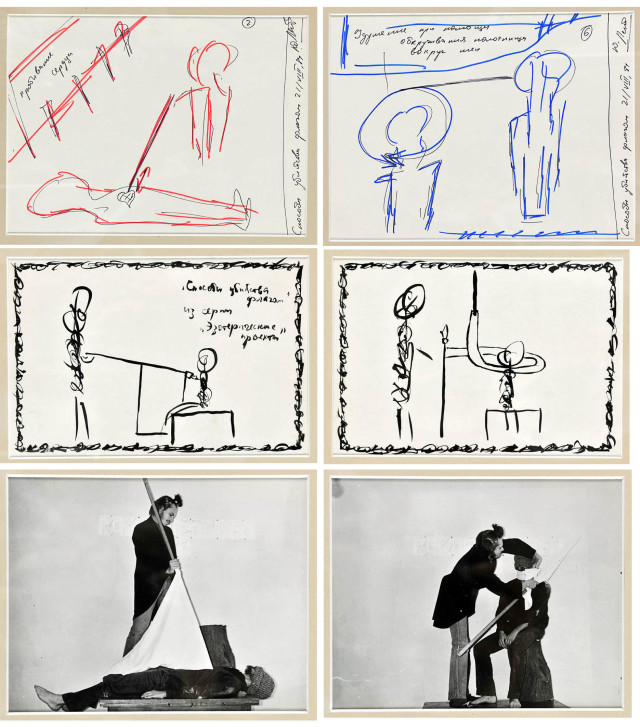

This was not visual art per se, but rather illustration of the texts: a sort of translation of dead ‘ platitudinous’ language into living human language, to illustrate how they were perceived by the common person. For example: international passports were unimaginable at the time. As leaving the borders of the USSR was not possible, the artists reacted by creating fantasy “passports” populated with absurd and fantastical “visas”.

The movement was delineated by it’s production of artistic objects which resembled the underground satirical magazines that were popular with dissidents. The drawings made by members of the movement and their captions elicit laughter even today – their bitter sarcasm conveys the environment of those years in a manner so powerful, that it retains it’s striking force decades later. Some, if not most, modern satirical magazines pale in comparison to the wit of those early works. It would be complicated – and not entirely necessary – to comment on the visual aspects of the work. This was a movement where every aspect of a work, visual as well as non-visual, was crafted to work together towards a greater and holistic idea.

Actions and performances such as the self explanatory “Cutting of Smoke” by Yuri Leiderman also played an important role for the movement.

1982 is conventionally regarded as the year Odessa Conceptualism was born. It was then that the meeting between Leonid Wojcekhov and Sergey Anufriev took place, resulting in the founding of the first group of Odessa conceptualists. Among its members were Yuri Leiderman, Alexey Kotsievsky, Igor Chatskin, Fedot, the “Perzy” and “Martynchiki” groups as well as myriad lesser known artists.

Why Odessa specifically?

Most likely this is because of the town’s proximity to the sea

The driving spiritual impulse of the movement itself was a peg on which to hang a critique of reality and life, with all the gusto that reflected Odessa’s famed spirit of “apathy” and bravado. The prickly artists involved with the project practiced a kind of irreverent “rascaldom”. Their aim was to assert their self-identification and determination through a particular kind of sarcastic criticism. This was a gesture distancing them from the establishment.It was a narrow circle, which, as it grew wider gave birth to ever more groups and fractions both inside and outside of itself. These groups would gather to spend time together and exchange ideas and criticism of their artistic production. These artists were young and most importantly, alive in the real sense of the word. They were not part of that ubiquitous, beaten down grey mass of Soviet society which was ready to submit to any order or directive (even those issued within the art world). They refused complacency and harshly mocked and rejected the mode of life which the USSR attempted to impose on them.

Most of the artists were forced to relocate to Moscow, where a collective was formed under the name “Inspectors of Medical Hermeneutics’”. This sub group exerted a great deal of influence over the Moscow conceptualists. However, by the early 90s, conceptualism had outlived its purpose. According to the words of the conceptualists themselves – “The statement has been made”.

Unfortunately, while the USSR may be defunct on paper, it does persist as a mode of consciousness for many. This is why conceptualism is not obsolete, and continues to be quite relevant in our day. The routines of life have changed only slightly, but the mechanisms of control remained in place. Art gained a dimension of seriousness – it now has a desperate need to speak with absolute sincerity and to emphasize important things.

Although… as always irony and sarcasm remain in style.