The band SINOPTIK first formed in Donetsk in 2011. Almost three years ago, they were forced to leave their home city by the war and venture forth in search of a new home. In 2016, they won the Global Battle of the Bands in Berlin and received the lofty title of “Best New Band in the World.” Now they tour all over Europe. Though the band has existed very briefly their story dramatic story is one of the most intriguing in the musical life of contemporary Ukraine. The band’s spirit was forged by the war in Eastern Ukraine.

We meet at their rehearsal base in one of the industrial zones of Kyiv. The zone , and thus the band are surrounded by steel, concrete and a chaotic cacophony of sounds that has become a familiar atmosphere for SINOPTIK — they have gotten used to disorder over the last three years. This disharmony contrasts markedly with the monolithic, stunning sound that hits the audience as soon as the trio mount a concert stage. They are well known by their fans for always giving a maximal effort and using their instruments to the maximum capacity and releasing a wave of energy that makes one stronger.

Life “Before” and “After” Donetsk

They readily admit however that things were not always like this. Dmitry Afanasyev-Gladkikh (vocals, guitar, keyboards), Dmitry Sakir (bass guitar) and Vyacheslav Los (drums) are not too happy about their early recordings. So why was their work different before? And what happened then to change their dynamic?

“Until 2014, we were children who thought that they had a lots of skills, but we were mistaken. We were boys playing at being rock’n’roll musicians, without having yet learned for ourselves about the complexity and gravity of the world. After the move, everything changed. It was as if we surfaced, were born in the real world. It turned out not to be as cheerful as we had imagined it before,” explains Afanasyev-Gladkikh. It is his nickname, “Sinoptik” (“Weatherman”), that gave the band its name. There is something fateful about this: the changes in the world “climate” influenced the fate of SINOPTIK.

The radical act of parting with the city of their childhood, Donetsk, was precipitated by the war that created millions of internal refugees within the country. Like many other citizens of the Donbas, the musicians fled along with only their families and most precious possessions: musical instruments, equipment and their passionate creative energies. The traumatic experience gave them a clearer and sharper understanding of themselves and the world. “When I lost my home, my friends and my community, I was left, in fact, a solitary man with a guitar in one hand and a laptop in the other. Until 2014, music was my hobby and passion, but now it became my life’s work,” Sakir admits. “I realized that in our life we have nothing except our inner world and the knowledge that we have accumulated. I lost my home, family business. I realized the value of what I carry inside me,” adds Los.

That first acute shock of experiencing life as a fleeting moment was generative in that gave SINOPTIK’s performances their power. Pain and the longing for home are intertwined with the discovery of new horizons. Now they are living in Kyiv and touring all over Europe. But every time, when finishing the last song, Afanasyev-Gladkikh crosses his arms over his head, with fists clenched. These are hammers — the miners’ symbol, one of the main visual markers of Donbas. The band members insist that even if someday they will have a chance to live in New York, their connection with their homeland will remain sacred.

The Cult of Sound, or Rock Lives

Of course, their impressive sound is a technical achievement and can not be attributed to their experience of war alone. Five minutes at the rehearsal studio with SINOPTIK is enough to understand — these people know how to work, dedicating themselves to the maximum. There is also the invaluable experience of Afanasyev-Gladkikh, who lived in England for two years in the beginning of the 2000’s, studied there and pursued a career. Dmitry still speaks about that time in his life with shining eyes and the emotional charge he got there has not run out, and is passed on to his bandmates.

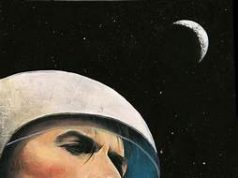

SINOPTIK has released three albums so far. The most recent, “Interplanet Overdrive,” came out in April of 2016. The band’s sound is that of vintage rock traditions clad in modern sound technologies. Psychedelia, blues, hard-rock, art-rock — everything has a place in their sound palette. A good metaphor would be to imagine Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath drinking tea in a kitchen, with members of Pink Floyd being somewhere in the background making coffee. Except, they would be surrounded not by the shabby walls of the past, but the fresh interiors of the 21st century.

In 2017, when rock music has been declared dead ten times over, I have no doubt that the trio from Donetsk represents a real living rock culture. The guys themselves don’t think about it very much in analytic terms. “I recently recalled the 90’s, when people all over the world were still going crazy at rock concerts. And now they listen to you like well-fed house cats. It’s not a bad thing — nothing lasts forever. So I prefer to stay away from wondering ‘is it rock? not rock?’, we just write songs, and that’s it,” Afanasyev-Gladkikh says.

Sakir continues on the theme: “Now all genres of music are thrown into a blender and mixed in any proportions. But the spirit of rock music is primarily in the delivery. If it carries a powerful charge, that means it’s rock music. For me, ONUKA, Justice or Antonio Vivaldi is rock music, I feel a charge and a drive in them. At the same time, some bands who call their music ‘rock,’ are completely meaningless for me.”

I agree with him. Obviously, the main indicator and essence of rock culture is not a guitar – that’s only a technical symbol. The power of dedication, the transference of extraordinary energy — that is rock in 2017. And in that sense, SINOPTIK band members are superior musicians with an original sound.

Like any true master understanding that perfection is unattainable, they doubt themselves and their mastery of the craft. “I can tell that the audience enjoys the performance, but I myself can’t be on stage and hear how we sound to them at the same time,” Afanasyev-Gladkikh says thoughtfully. Dmitry continues: “We played in the Czech city of Boskovice, there was a band called Dirty Blondes playing before us — they played frantically from beginning to end and people were going crazy. These guys jump, destroy guitars, set fire to the drummer’s plates. Very cool. And, looking at this, I don’t know how the audience would receive us, because we push completely different buttons.”

Triumph at Global Battle of the Bands

When they won the competition in Berlin in May 2016, I thought: “Was there really no band, in the whole world, that could compete with SINOPTIK?” It was a feeling of pride, mixed with surprise. Now, a year later, I ask the trio: what is it about them that other contestants did not possess, that led them to victory?

Los begins: “Self-confidence helped a lot. The other contestants clearly lacked it. We wanted to win, but we weren’t afraid to lose. We just went out and rocked it. The competitors did not give themselves fully, some looked at the floor while they played. There was no delivery, no contact with the audience.” Sakir picks up on the same thread: “We played proven songs that didn’t leave anyone in the audience indifferent. We were well prepared, and after three concerts on the tour we already had momentum, like an express train. Personally, I had a very positive and game mindset, I climbed onstage as if it was a fighting ring. Like athletes do — we shake hands, and then we fight.”

SINOPTIK is a unified organism — exactly because it comprises unique personalities. “I once thought that a band should be made up of people who think the same, have the same lifestyle and communicate constantly. Over time, I realized that it works completely differently. We have a lot of disagreements in the group, but there is a feeling of moving towards a common goal,” explains Afanasiev-Gladkikh.

They don’t spend all their time together, they don’t engage in any special team-building, and between tours they often spend their free time separately. “But even when we are not near each other, there is a connection between us that is always felt,” says Los.

Yes, it is felt, especially clearly when they plug in and start to play. Music and inspiration are the glue that holds SINOPTIK together. My lofty reflections on this subject are interrupted by Sakir, the main master of ironic remark in this band: “Every day I spend an hour or two on the phone with Dima on different matters. Even if we don’t meet up, we won’t leave each other alone.”

European Joys

Over the past year, they traveled a dozen European countries, from the Baltic to the Mediterranean Sea. Spain, Germany, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Romania… I ask them what they found in Europe that does not exist in Ukraine’s music industry. “Over there, this field has become a mature business with a mature audience,” explains Sakir.

Afanasyev-Gladkikh wants to talk about something quite different: “There is no aggressive snobbery in Europe. They treat their own and foreign artists with a certain spirit of equality. In Ukraine, if you’re trying to do something, there will always be a group of countrymen who will trash you. A recent example — the reaction to O. Torvald’s victory in the national competition for “Eurovision.” All these people that attacked them! But it’s a well-deserved victory. Zhenya Galich, the band’s leader, did not wake up suddenly famous after some talent show. He’s been doing this for ten years, persistently, working hard with his team. And this is the result.”

They point out that in Europe you are accepted and respected for who you are. No matter how you’re dressed, made up or extravagant in manner. “In one Polish town, we saw a girl whose face was almost completely covered in piercings. She was about 35 years old, dressed strangely, but no one was pointing at her. People express themselves. The same goes with music,” recalls SINOPTIK’s vocalist and guitar player. “In Ukraine, it’s hard to imagine a rock band with a vocalist in a wheelchair, but we played with a band like that in Vienna and no one had a problem with that,” adds Dima Sakir.

According to him, in Ukraine, there are still big problems with treating people who are “different” adequately: “Some people in Ukraine continue to see us the same way — we are still just some upstarts from Donbas to them. Time will tell who is right.”

Absurdity of War

They may have left Donbas, but they certainly have not left the war behind. What happens there is reflected in their emotions, moods and thoughts. They try not to get involved in disputes, but sometimes they can’t help it. When, in Budapest, Afanasyev-Gladkikh was asked what was happening in Ukraine and if it was true that hundreds of people died there, he wrote a desperate post on Facebook. That is wasn’t hundreds, but tens of thousands who died. That it continues to this day. That he dreams about peace.

“After I wrote it, I was so attacked! And then I realized that this absurdity in Donbas will not end while we have this mess in our heads. Until people on one side of the front line understand what people feel on the other side. It is an incredibly difficult task. The solution lies in understanding that we first need to change ourselves before changing the world around us,” Dmitri points out with emotion in his voice..

Vyacheslav Los joins our dialogue: “These problems around the world are more or less the same. Most people are not into educating themselves, they live with goals and values that were invented by someone else. They listen to the TV and are happy to be brainwashed, because nothing worthwhile is happening in their lives. They can’t be bothered to do anything and make their own decisions.”

Sakir holds equally subversive opinions: “There has never been true political freedom or freedom of speech anywhere in the world. But you can’t take away the freedom of conscience from a human being. The more often you act according to your conscience, the better your life will turn out. Ultimately, you will receive from the world only what you put out it into. But it’s easier for people to blame someone else.”

I listen to these young people and I understand that their words are not hot air, but a result of real suffering. They have experienced firsthand the absurdity of the war in Donbas, which reminds them of George Orwell’s novel “1984.” They can’t close their eyes to this and sleep peacefully at night just because they are safe in Kyiv, five hundred kilometers from the front line. They accumulate this pain and despair in themselves, transmute them and give them back to the world in the form of the healing energy of living sound.

Igor Panasov is a music critic based in Kyiv.