The “Ltava” Honored Ensemble of Song and Dance in the northern Ukrainian city of Poltava has drawn dedicated volunteers and performers to help it keep alive regional dance traditions. An American dancer joins up with the Poltava collective to help keep local Ukrainian tradition flourishing.

Rehearsals for the dance portion of the “Ltava” Honored Ensemble of Song and Dance take place in a large, mirrored room on the second floor of the Poltava city cultural building. On a particularly sunny Sunday morning, balletmaster Elena Kulko, who leads the dance ensemble, stood at the front of the room leading the group in barre exercises in the Western Ukrainian style.

“I wonder, do other countries have exercises at the barre?” Kulko wondered. The group paused while they wondered out loud whether other folk dance traditions, like Ukrainian folk dancing, have specific exercises that are typically done at the barre. “Georgian folk dancing doesn’t have barre exercises, but they do have a lot of people,” added one person. “Yeah, while we have barre exercises and almost no people,” responded another.

The “Ltava” Honored Ensemble of Song and Dance was founded in the early spring of 1957 by Valentine Mishenko, a graduate of the Kyiv State Conservatory. Ten years later, the group would receive the distinction of being designated as an “Honored” Ukrainian Ensemble of Song and Dance. The sobriquet “honored,” was the highest distinction that was given to amateur folk Ensembles at the time. This distinction is no longer awarded, but it has remained a part of the ensemble’s identity.

The original idea that Mishenko pursued when founding the ensemble was to forge a collective that would represent the three foundational aspects of Ukrainian folk culture: songs, music, and dance. In pursuit of that goal, Mishenko travelled to villages all around the Poltava region to transcribe the words and music of the quickly disappearing regional songs.

The dance collective is a true testament to the resilience of Ukrainian tradition: it is an award-winning Soviet folk collective, whose songs and dances have been recorded from the memories of people living before the Soviet occupation. It still meets every Tuesday, Thursday and Sunday night. The ensemble proudly retains the obsolete distinctions of a former time, while continuing to accrue new accolades in competitions and performances all around the country and abroad. The costumes – and there’s a different costume for each dance and village – are beautifully ornate, made from quality materials, and are apparently old as time itself. This all demonstrates either the fierce commitment of a select few to the preservation of Ukrainian folk culture, or, simply Ukrainian folk culture’s enduring charm.

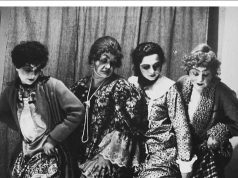

The dance troop of “Ltava” is composed of a diverse group of people. They meet three times a week and rehearsals are always accompanied by a live accordion player, the Ensemble’s concertmaster Sergei Yakovenko. The size of the group fluctuates from week to week. Sometimes, on a Sunday morning, almost twenty people will squeeze into the dressing room, while at other times a meager four people will arrive. There are some who come only to rehearse and don’t have the time or desire to perform, while others arrive on the day of the performance, having only rarely appeared for rehearsals.

Some are teachers. Some work in finance. There is a musician and a large number of students. Some arrived in 2009, while others first came in 2013, a few in 2016 and there’s even one young man who only joined in February. All these people have committed a solid six hours a week of their free time to travel through the dark and the cold to their folk dance rehearsals. Those that arrive late are fined two Hryvna and to further drive home the point, there is a sign taped to the door of the changing room that reads explains the acceptable reasons for not attending a rehearsal: 1. You died, 2. You got sick and died, 3. You were killed.

But no one really means it: if you’re sick, stay home. If you’ve been away for months and months, you’re always welcome back. If you’re a terrible dancer, you should come anyways. Some in the collective began dancing at five or six years of age and some began at twenty or even later. You may never be a lead soloist, but like an army platoon, folk dancing needs disciplined numbers. Everyone will say that the reason they keep coming back to “Ltava” is that they simply love dancing. And there is just no other form of dance that gives and displays such unbridled joy as Ukrainian folk dancing.

“Folk dancing has plot, humor and strength… it has the spirit of the people,” said Kulko when asked how Folk dancing is different from other types of dance that she has studied. All of the Poltava-specific dances that “Ltava” performs can still be traced back to different towns around the region in which they had first appeared. An obvious example is the dance “Sanzharovka” from Novi Sanzhari. “Rohoza,” or “Cattail,” can be traced back to the town of Kobelyaki. In “Rohoza,” the dancers weave through one another as though they were themselves cattails and were making old-style shoes called lapti.

These dances were recorded by another foundational figure in “Ltava” history, Vladimir Tulyaev. The dances originate from times when, on festival days, the people of Poltava region would come out on the streets and dance. In one village they will clap a certain way, others will leap differently, spin, circle and stomp. Just as Mishenko did with the songs, Tulyaev traveled to record these village peculiarities and transformed them into choreography. The dances that “Ltava” now perform seek to preserve these minute differences while adding a certain level of technique.

Andrei Serov is a student of choreography at the V. G. Korolenko Poltava National Pedogogical University. Like many Ukrainian children these days, he began dancing when he was seven. He didn’t enjoy it very much back then, and after having quit for several years he decided to give it another try. He is now one of the lead male soloists. When asked why he has committed his time to the “Ltava” collective, Serov replied: “Because… Ukrainian culture is important to me as a Ukrainian… as a great man once said: “Every nation only exists as a long as it’s culture survives”. One can could many different answers to that question, but for me it is fairly simple: I love all of it, and this collective; great people come here, and we try to illuminate the world with our movement and emotions.”

The Ensemble of “Ltava,” strikes one as a unique experience from the moment of first encounter. There is no cost for entry, all that is asked and expected is commitment, hard work, and a deep love for dance. The dancers are open and welcoming and, even if you’re American and spend most of your time struggling along with the dances in absolute silence, Ukrainian folk culture is there for you to engage with as long as you’re willing to put in the effort.

The perseverance of “Ltava” might be interpreted as a testament to the strength of the Ukrainian spirit, but, interacting with the dancers of “Ltava,” there is no visible sense of struggle or effort. The devotion of these dancers to their art and culture is effortless, simple and poignant. The importance of preserving these unique and ephemeral works of art seems secondary to the love of dancing and the community that they have found in the Ensemble. If anything, “Ltava” demonstrates the organic and deeply rooted nature of Ukrainian culture, and the widespread sense of connection that is still felt today to folk traditions.

Isabel Meigs is an American Fulbright Scholarship recipient based in Poltava.