The process of implementing the recently passed de-Communization laws has not been particularly smooth. The debates over Communist-era place names are roiling Ukrainians’ efforts to redefine their national identity. This article first appeared in a slightly different form originally in the American Interest.

In the 25 years since Ukraine officially separated itself from the Soviet Union, decommunization has been a slow, crawling fact of everyday life. Fairly quickly upon Ukraine’s independence, the most anti-Soviet towns, located mostly in Western Ukraine, tore down their ubiquitous statues of Lenin. But in many other parts of the country, the Lenins simply remained on their plinths. Tearing them down was too expensive, and was not seen as a priority. A few street names were changed here and there, but most towns continued to have a “Lenin Prospekt”. In one Ukrainian city that I long ago called home, the main boulevard was named for the 1917 October Revolution that first brought the Bolsheviks to power.

This most recent phase of decommunization began in earnest during the Maidan demonstrations of 2013 and 2014, when pro-European protesters destroyed the Lenin statue that still stood in the center of Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital. It was the beginning of what would come to be known as the ‘Leninopad,’ or ‘Felling of the Lenins.’ All around the country, hundreds of Lenin statues—and sometimes statues of other Communists—were toppled in a kind of spontaneous attempt by Ukrainian society to reclaim its historical identity. By one count, 1,221 Lenins have fallen since December 2013.

In May 2015, Ukraine’s President approved a law that mandated the changing of the names of all of Ukraine’s towns, cities, municipalities, and villages from their Communist moniker to something, well, not Communist. Street names, squares, schools, and even soccer teams were also put up for name changes.

Local municipalities were given a deadline of November 21, 2015 to implement this toponymic revolution. Where decisions were not agreed upon locally, the regional authorities were given six more months, until May 21, 2016, to make changes. Now, after that final deadline, the names that could not be agreed upon by local authorities—including those of eleven towns and cities—are to be determined by Parliament.

The urgency for new place names has proven to be one of the most contentious issues in modern Ukrainian politics. It has forced local polities to take stock of themselves and think about the kind of place that they want to become and the image that they wish to project to the world. Their choices also had to fit within the framework set forth by the Ukrainian National Memory Institute, a controversial government organization that has been accused of whitewashing certain of the more unsavory aspects of Ukrainian history.

One of the most pressing problems was the name of Dnipropetrovs’k, Ukraine’s fourth largest city and a major industrial hub. Its name was a combination of the river that flows through it—the Dnipro River—and an early head of the Ukrainian SSR, Grigory Petrov. Known as Ekaterinoslav, or, Glory of Catherine [the Great] during Tsarist times, it was determined after much debate that the city should be known simply as ‘Dnipro,’ after the river, and should not hearken back to its old identity.

Some places have chosen to their pre-Communist names; the eastern Ukrainian city Artemivs’k is now again called Bakhmut. Others have made cosmetic changes like removing the adjective “Red” that sat before the names of many towns.

Still others have had seen their renaming efforts descend into squabbles. The regional capital of Kirovohrad, and thus the region that surrounds it, were named for the Bolshevik leader Sergei Kirov, after he was famously assassinated in St. Petersburg in 1934. Founded as Elizavetagrad, or ‘Elizabeth’s City’, the municipality has been wracked by heated debate over what it should rename itself. Its case now sits before the Ukrainian Parliament, which is also having some difficulties. With seven new names under consideration, a parliamentary committee has recommended “Kropivnitskiy”—after a 19th century dramaturg—as the new name, but no final decision has yet been taken.

While Kirovohrad seems ready to accept its fate, the town of Komsomols’k is not. Founded in the 1960s, and named for the Communist Youth International, it was loath to give up its name, could not agree on a new one, and is deeply unhappy with the name Parliament has bestowed upon it: Horishni Plavni. The new moniker, which roughly translates as “Place above the reed beds,” has united residents against it. Where the old name rang of youth, future, and progress, ‘Horishni Plavni’ is archaic, barely comprehensible to most Ukrainians, and makes a midsize industrial city sound like a backwoods village.

The process of relabeling local entities has been somewhat easier, but no less difficult. In the Poltava region in central Ukraine, over 600 streets were renamed. The new appellations came from a variety of sources. Some have been reverted to their pre-Soviet names, others have been named after famous Ukrainian historical and cultural figures like the composer Ihor Shamo, or been named in honor of a local figure or dignitary.

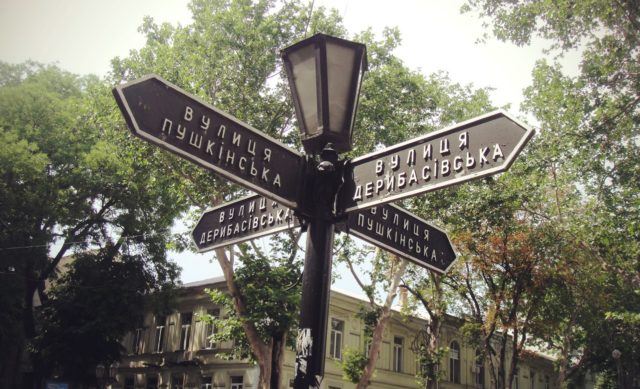

Some streets, like Odessa’s “Heroes of Stalingrad” Street, have retained similar themes; it was renamed “Heroic Defenders of Odessa” Street. Odessa now also has a Liverpool Street, chosen as Odessa and Liverpool, England are sister cities. A few hours away, in Mykolayiv, the until-recently ubiquitous “Lenin Street” was given the anodyne and entirely uncontroversial tag “Central Street.”

In Odessa, where politics can sometimes be quite volatile, the seemingly haphazard style of sweeping away old names ran into a wall. The Ukrainian National Memory Institute had decreed removal of all streets named for the revolutionary Czeslav Belinsky; Odessa instead removed the name of 20th century Russian intellectual and literary critic Vissarion Belinsky. The uproar at this sin was tremendous.

Of course, getting citizens to adjust to these changes is another task entirely. While Google Maps may have already made the necessary adjustments, residents who have lived their entire lives on Red Army Street are unlikely to do the same. That most localities are either unwilling or too cash-strapped to change the physical signage only further complicates matters.

Doubtless, some of these new names will change in the years to come, as Ukrainians delve deeper into their local histories and determine the kinds of places they wish to become. With this wave of seemingly superficial changes, Ukrainians are at last being given the chance to begin to delineate themselves from their neighbors; the era of Communist faux-equality is over.

But the point to which this decommunization should extend remains up for debate. Many worry that the past—and the lives that their parents and grandparents built—is being erased. Others are concerned that as Communism—and indeed much of the 20th century—are scrubbed from the maps and history books, the country will skip over the societal discussions and internal examinations necessary to build a unified polity. Ukraine’s Communist and, yes, Nazi history does exist and will not simply disappear overnight, especially if it is not confronted directly. As the country takes steps to build its future, finding the delicate political balance between old and new, past and present, nefarious and righteous, will set the stage for the Ukraine that will hopefully emerge from this time of troubles.

Hannah Thoburn is a Research Fellow at the Hudson Institute, where she focuses on Eastern European politics and the transatlantic relationship.