This essay is an adaptation of program notes prepared for two concerts highlighting Jewish music from the Pale of Settlement that the author helped research and organize in greater Washington, DC, including at the Kennan Institute at the Wilson Center.

The image of a refugee is one of the most enduring images associated with the 20th century Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. Already in late 19th century and early 20th century, Jews constituted a disproportionately large portion of the populations fleeing these territories en masse as pogroms, civil war and revolution swept through them. World War I, the two revolutions of 1917, and the civil war led to further waves of migration, with refugees reaching such faraway places as New York, Paris, Buenos Aires, Palestine and later Israel.

Beside the suitcases stuffed with their most prized possessions, the refugees carried with them to the new lands their favorite songs. As they settled into their new homes, they adapted those songs to their new environments, creating unique musical fusions. Many of the songs that they brought with them received notice in their new countries and even became new hits. And while they were invariably dubbed as “Russian”, most of them, in fact, originated from the periphery of the empire. Their true source was to be found in the fertile musical ground of the Pale of Settlement — particularly its heart, today’s Central and Western Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus.

It was in these lands, where borders perpetually shifted, and languages, cultures, and ethnicities mixed and mingled freely, that nurtured an organic blending of Yiddish folklore with the musicality of Ukrainian folk songs, Russian Orthodox liturgy, the breadth of Kuban Cossack folk songs, and rousing Moldovan dance tunes. The harmonic languages of German and Italian music mixed with the Christian Orthodox musical idiom in the gorgeous Jewish liturgical melodies spilling into the streets of Odessa’s main synagogues. The growing urban culture, at different times infused with the nostalgic tunes of Russian urban romance, Argentine tango, American foxtrot, and patriotic Soviet song, added its own layer.

Even some of the best-known Soviet composers, such as Isaak Dunayevsky (who is fittingly enough an ancestor of Vladislav Davidzon, the chief editor of The Odessa Review) — whose light operata enthused songs formed the heart of Soviet popular culture and found a new life in Israel — had come from a Ukrainian town in the Pale of Settlement. Having come of age before the revolution in a family with a strong cantorial tradition, Dunayevsky would have soaked up both Jewish liturgical and folk music as well as the music of the other traditions that would have permeated his life. It seems impossible that those influences would have no effect on the music that he created throughout his prolific career.

From Odessa To Brooklyn

One international hit that was born in Ukraine and traveled with Jewish emigrants to the United States — the eternal destination for Jews fleeing the Russian empire — was “Bublitchki / Bagelach”. The song is a reflection of the urban culture of the 1920’s Odessa. Formally speaking, the original song’s heartbreaking story of a poor young woman begging passers-by to buy bagels from her so that she can earn a living is somewhat undercut by the upbeat melody.

When Jewish immigrants introduced the song to Brooklyn, it became a hit among Yiddish-speaking New Yorkers. It is said that the famous Barry Sisters (whose original last name was Bagelman!) were discovered while humming the tune. Once the two became famous, they reportedly started every performance with this song. The song’s birthplace, Odessa, the city that brought forth numerous musicians and performers, reminds us of the city’s singular contribution to world culture.

To The Gaucho Land

While the United States and Palestine are the better-known destinations for the Jews from the Pale of Settlement, for a significant group, Argentina would become the promised land. In the late nineteenth century, Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a German Jewish banker and philanthropist, bought land in Argentina with the goal of establishing a Jewish agricultural commune and resettling Jews in the New World in Argentina, Canada, and the United States.

In 1889, 815 Jews from Kamianets-Podilskyi in Ukraine landed on the docks of Buenos Aires, South America’s equivalent of New York as the primary destination for immigrants. They quickly made their way to the province of Santa Fe. There, 383 miles from the capital, they formed the first agricultural Jewish colony in South America, Moisés Ville (Moshe’s Village). In the ensuing years, additional groups from Grodno, Bialystok, Bessarabia, and other parts of the Pale of Settlement arrived.

Somewhat improbably, yet also understandably, these disempowered groups found Argentina’s gaucho culture appealing. The love of freedom — and the ability to seize it — along with the strength and independence that the gaucho culture represented brought out something the new arrivals wanted to make their own. Thus a new social group was born, the Jewish gauchos.

The song that represented this culture the best was Yiddish-language “Moisés Ville”. It expressed the aspiration to become a free person, as in these lines: “On the plaza stands a man, a saloonkeeper for sure, with baggy pants and slippers on his feet. Through his moustache, he whistles a Spanish melody. You can be certain that this saloonkeeper is a Jew!” Aspiration of this sort — for freedom and comfort in a new environment — is both uniquely Jewish as well as universal desire for any group seeking its fortunes in a new land.

From Soviet To Israeli

As the Zionist project gathered steam in Europe, the number of people in the Jewish Settlement (Yishuv) in Palestine began to grow. Hundreds of Soviet songs were translated into Hebrew, acquiring new identities along the way. Frequently the lyrics were rewritten entirely, and only the melody remained to remind listeners of the song’s origin. The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 led to a further musical blossoming, with some of the greatest Soviet hits acquiring a new life on the Mediterranean shores of Tel Aviv and Haifa.

The famous Soviet song “Smuglianka”(A swarthy girl) was written in 1940, in the style of a Moldovan folk song, to commemorate the female partisans of the post-revolutionary Civil War. It became a Soviet favorite and eventually found its way to Israel, where it was given a new title, “Neurey zahav” (Youth of Gold). As in the original, the Hebrew lyrics speak about a young man falling in love with a beautiful young woman, but the context of partisan fighting is no longer there.

“Serdtse” (Heart), a popular 1930’s Soviet tango composed by Dunayevsky, also traveled to Israel. There it became known in its Hebrew version as “Rina” — a young woman’s name. But the romantic language of the original (“My heart, I am so grateful that you can love so much!”) was replaced in the Hebrew version with satirical verses mocking sentimental love.

A song that merits particular attention in this category is “Siniy Platochek” (The Blue Kerchief), a Soviet song forever associated with World War II. Originally composed in 1939 as an instrumental waltz by a famous Polish Jewish composer, Yezhi (Jerzy) Peterburgsky, the song presents the first-person words of a soldier as he speaks about leaving his lover, then addresses her directly, confident that she will keep the blue scarf she wore on the evening of their last meeting as a sign of her love for him.

Jerzy’s story is itself worthy of a novel and is emblematic of the era. Born in prewar Warsaw to a famous Jewish musical family, the Melodistas, Jerzy formed a partnership with his cousin, Artur Gold. Together they established a tango orchestra and entertained fashionable Warsaw with their tangos written in the Argentine tango style, which was conquering 1930’s Europe and the Soviet Union. Some of Jerzy’s tangos, such as “Utomlyonnoe Solntse” (The Tired Sun), which was translated into Russian, are performed to this day in Poland, Russia, Ukraine, and even the modern-day tango halls of the United States, Europe, and Argentina.

When the Soviet Union annexed part of Poland in 1939, Peterburgsky found himself in the Soviet Belarus. It was there that he composed the melody of the “Blue Kerchief”. The waltz became popular in the pre-war Soviet dance halls. But it was not until early 1942, when the rising star of Russian popular music, Klavdia Shulzhenko (herself born and raised in Kharkiv, Ukraine), performed it as a song with lyrics reflecting the war, that it really hit the right emotional tone with audiences. It became an instant classic. Performed during the period of the war when the Soviet Union was suffering crushing defeats (Shulzhenko’s native Kharkiv fell under German occupation in October 1941), the song put a human face on the collective suffering that was unfolding for the entire country. It came to symbolize war’s emotional toll and offered inspiration bound up with the promise that those separated by war would be reunited.

But as the Soviet audiences turned this song into an enduring hit, few knew what happened to its author and his family. Gold died with the majority of Warsaw Jews in Treblinka, where he was forced to entertain his tormentors up to the last moment by performing the very tangos he and his cousin had composed and played in prewar times. Peterburgsky miraculously escaped the near-complete annihilation of Polish Jewry and after the war moved to Argentina, where he worked at Radio el Mondo and Teatro el Nacional.

After the war, Avraham Shlonsky, an Israeli poet born to a religious Jewish Chassidic family in Kryukiv, Ukraine, translated the song into Hebrew. The new title, “Tkhol haMitpakhat”, retained the reference to the blue scarf, and the text kept the romantic elements of the song, but it did away with the World War II context of the original.

A World That Is No More

That the song tradition of the Pale of Settlement, with its rich interweaving of cultures, languages, and ethnicities, would give rise to a rich musical culture is hardly surprising. That some of the songs that came from there became enduring hits around the globe is a gift to be treasured. The brunt of the 20th century’s violence came down particularly harshly on this world, wiping out significant parts of it.

Eastern European Jewish culture in particular came to the brink of annihilation — as did the people itself. “Ukraine without Jews” — the poignant essay by Vasily Grossman, who, as a war correspondent, re-entered Ukraine in 1943 with the Red Army — reflects the writer’s shock as he tried to comprehend the extent and consequences of the destruction of a people.

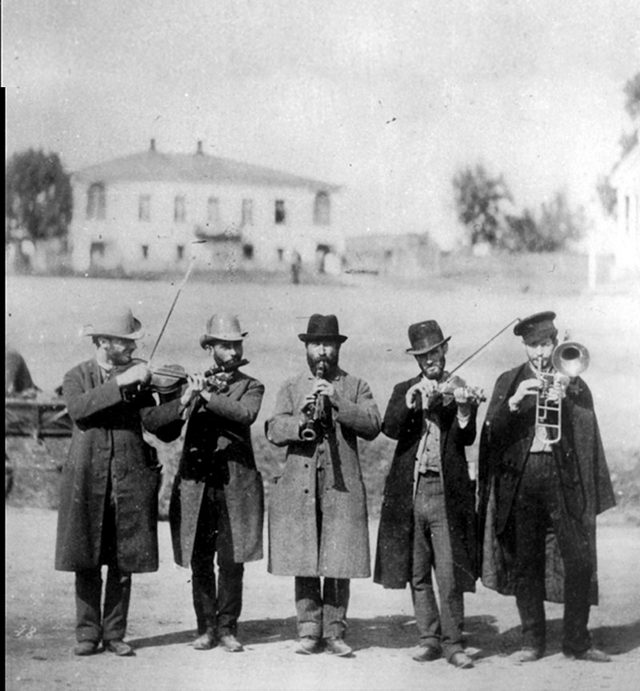

Relatively little material evidence remains of the richness of that culture. That makes its remnants all the more precious. It is impossible to look at the photos by Roman Vishniak — the Russian-born photographer who photographed Jewish life in Eastern Europe throughout the 1930’s — without the thought that within a short span of time, virtually every person in the photos and the world they lived in would be destroyed.

There is an equivalent to Vinshniak in the musical world: Moshe Beregovsky, the famed ethno-musicologist who was born outside of Kyiv at the end of the 19th century and received his musical education at the Kyiv Conservatory. In the late 1920’s, he began to collect the music composed and sung by the Jews of the now abolished Pale, believing passionately that it deserved to be collected and disseminated throughout the world. By the beginning of World War II, Beregovsky amassed an unprecedented phonographic collection of 4,000 Jewish songs. Not content with that, in 1944-1945, he traveled to the just-liberated Jewish ghettos and interviewed the few remaining survivors, adding 70 unique songs created and sung by ghetto inhabitants.

Beregovsky’s Jewish folk music collection, comprehensive and wide-ranging, which was thought to have been lost, was rediscovered in the 1990’s in Kyiv. It is the largest collection of Jewish folklore in the world. That it has survived against all odds is a miracle in itself. That with its help we can learn about the broader musical tradition of the Pale of Settlement is a reason to treasure it all the more.

(The author would like to thank Hazzan Dr. Ramón Tasat and Cantor Natasha Hirschhorn for generously sharing their expertise on the subject.)

Izabella Tabarovsky is a Senior Program Associate with the Kennan Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, DC. She studies politics of historical memory in the post-Communist space and her writings have appeared in Newsweek, National Interest, The Tablet Magazine, Times of Israel, and the Russia File.