Despite the fact that almost half of all Jewish victims of the Nazi Holocaust were killed on the territory of the Soviet Union, their Jewish identity was for decades effaced by Soviet policy. It was the policy of the Soviet Union to systematically minimize the fact that Jews were specifically targeted during the Holocaust. However, despite this policy, the Holocaust was represented in some Soviet films. Olga Gershenson, the author of the groundbreaking 2013 study “The Phantom Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and Jewish Catastrophe”, reflects on the relationship between the history of the Soviet film industry response to the Holocaust, and the future of Ukrainian film.

Some million-and-a-half Jews lost their lives during the Holocaust in Ukraine. They were executed, drowned or burned; they were herded in ghettos and camps, and then killed. The Nazis instigated and organized the killing, but some Ukrainian locals took part. And yet, this genocide of unprecedented proportion barely registers on screens, neither in films made in the Soviet era nor more recent ones. Despite some strides that the new Ukrainian government took in commemorating the massacres, much remains to be done in bringing the history of the Holocaust — what the historians call “the dark past” — to light in Ukraine.

That obfuscation of the Jewish catastrophe has roots in long-lasting Soviet policies. Although the Soviets never denied the Holocaust, in actuality any attempt to speak of Jewish victims was silenced. The Holocaust was not to be treated as a unique and separate phenomenon. Instead, it was universalized or externalized — subsumed as part of the overall Soviet tragedy or located outside the borders of the Soviet Union. Both of these mechanisms were used to silence discussion of the Holocaust: universalization allowed the Soviets to cast Slavs and communists as the main target of Hitler’s attack and to erase Jewish victimhood; externalization was used to avoid any implication of local bystanders or Nazi collaborators, and it absolved the Soviet leadership from any historic responsibility for mass Jewish losses on their soil. As a result of this approach, there was no official commemoration of the Holocaust in the Soviet Union.

These policies started taking shape during the war, when the Soviet propaganda machine churned out tremendous amounts of newsreels and documentaries, including those depicting Nazi crimes in Soviet territories. But the footage was edited to obfuscate the fact that most of the murdered victims were Jews. An award-winning documentary, “Moscow Strikes Back” (“Razgrom Nemetskikh Voisk Pod Moskvoi”, 1942), represents all of the human losses as generically “Soviet”, but the narrative of the film implies that the issue is one of Russian national victimhood. Similarly, the wartime documentaries of the celebrated Ukrainian filmmaker Oleksandr Dovzhenko emphasized the Ukrainian identity of the victims, avoiding altogether any mention of the Jewish genocide. Even the Soviet documentaries depicting the liberation of the Majdanek and Auschwitz death camps, did not state that most of the victims were Jewish.

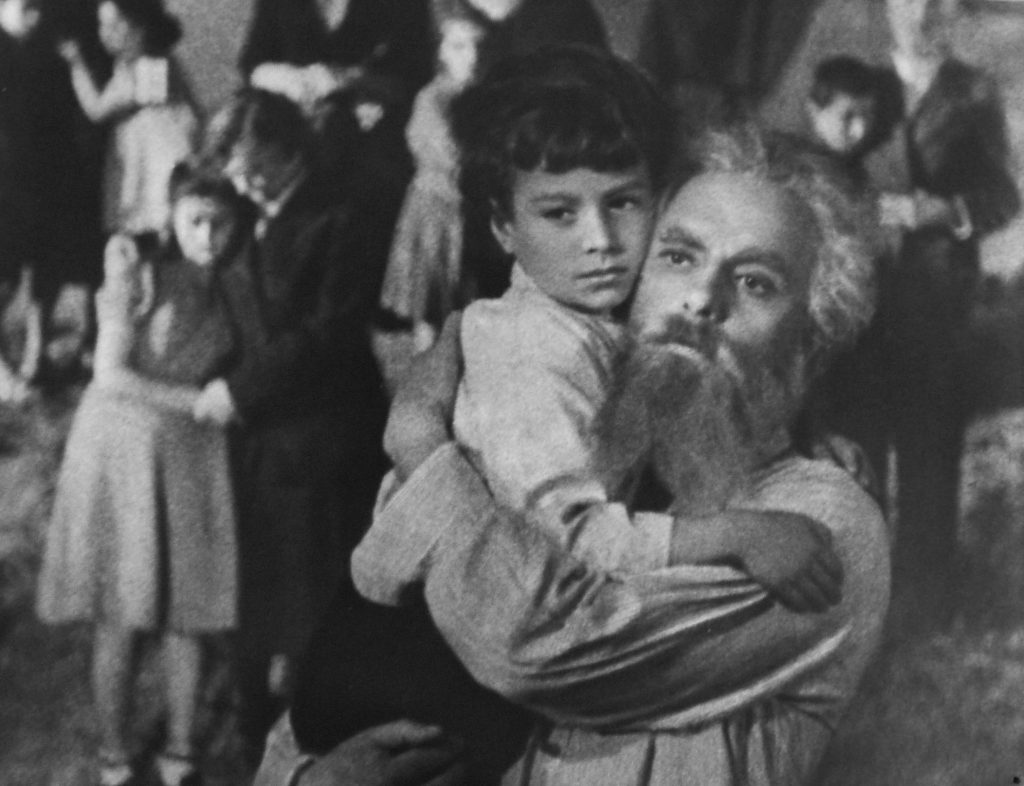

Feature films made during the war tell a similar story: Jews, even if marginally present in the original screenplays, were written out of the cinematic narrative of the war. And yet, some filmmakers attempted to acknowledge and commemorate the Holocaust in the face of Soviet censorship. The first, and arguably most significant of such films, was “The Unvanquished” (“Nepokorennye”, 1945), directed by the Odessa-born Mark Donskoi. Remarkably, “The Unvanquished” was not just the first Soviet film that portrayed the events of the Holocaust — it was one of the first Holocaust films worldwide. Its central and most devastating scene depicts a mass execution, which was filmed in Babyn Yar in newly-liberated Kyiv, the place that came to symbolize the Holocaust in the Soviet Union. Although the story of Dr. Fishman (played by the Soviet Yiddish actor Veniamin Zuskin), who was executed in the ravine, and his young granddaughter, who was saved by a sympathetic Ukrainian family, is only a subplot in a broader narrative, it is undoubtedly the most moving and memorable plot line.

The execution scene in “The Unvanquished” created the very first image of the Holocaust on Soviet soil, which is also referred to as “the Holocaust by bullets”. While this depiction was not historically accurate, it was cinematically powerful. At least in this scene, the particular Jewish predicament was neither universalized nor externalized. Alas, this film was an exception, not the rule. In the postwar era, as Stalinist policy grew more anti-Semitic, “The Unvanquished” was removed from the screens and from festival programs. The “Black Book”, a collection of writings and documents memorializing the Holocaust on Soviet soil — including Ukraine — was destroyed. Many Jewish public figures were arrested, persecuted, or killed. During this dark era, the subject of the Holocaust was off limits for filmmakers.

A period of relative liberalization in the late 50’s-early 60’s was a time of renewed interest in films about World War II in the Soviet Union. Although more personal and reflective than before, most of these new war movies did not touch upon the Holocaust at all, as if it had never happened. But several films created by courageous filmmakers were the exceptions. They were repeatedly censored: a Belorussian thriller “Eastern Corridor” [“Vostochnyi Koridor”] (1966, dir. Valentin Vinogradov), an Uzbek drama “Sons of the Fatherland” [“Syny Otechestva” (1968, dir. Latif Faiziev), and the most famous of them — the Russian “Commissar” (1967, dir. Aleksandr Aksoldov). This film had a remarkable history: set in a Ukrainian town during the post-revolutionary Civil War, it features a relationship between a Russian commissar woman and a poor Jewish family. In the key scene, portrayed with great emotional force, the commissar has a vision of the Holocaust to come. Because of that scene, “Commissar” was banned, and the reels languished in limbo for twenty years. The film was finally released only during Perestroika, in 1987, to great international success.

Not every censored project was that lucky. Another screenplay, “Our Father”, based on a story by the famous Soviet writer, Valentin Kataev, written in the 1960’s, was also a non-starter for Soviet censors. The plot tells a devastating story: a nameless Jewish woman wanders the streets of occupied Odessa with her little son, hoping to hold out until the deportation ends. She tries to find shelter from the cold and a safe haven for her boy, but to no avail. Both freeze to death. The censors forced numerous changes on the screenplay, only to ban it in the end. This long-suffering screenplay was finally made into a film in the Perestroika era, when the Soviet censorship retreated. “Our Father” (“Otche Nash”, 1989; dir. Boris Ermolaev), sadly, resulted in a strange allegorical tale stripped of historic detail and overloaded with Christian allusions and dark symbolism.

Several other films made during that time focus on the events of the Holocaust, none of which are very memorable or significant. For instance, “Exile” (“Izgoi”, 1991; dir. Vladimir Savel’ev) tells of the tragic fate of a Jewish Polish family in occupied Ukraine. It is beautifully shot, but the story is told in a melodramatic and even sensationalist way. By far the best of these films was “Ladies’ Tailor” (“Damskii Portnoi”, 1990) by Leonid Gorovets, a Kyiv native. Set in Kyiv on the eve of the mass execution in Babyn Yar, it tells the story of an old Jewish tailor (played by beloved Soviet actor Innokenti Smoktunovsky) who spends the last night with his family in their soon-to-be-lost home. The film ends with a procession of Jews being marched to Babyn Yar — that is to certain death. But the film’s treatment of the Holocaust is limited by heavy-handed symbolism and a simplistic representation of complex historic events, issues that that were characteristic of Perestroika-era films. During the period when those films were made, the Soviet economy collapsed, and the normal channels of distribution were cut off. Thus, these films were barely seen by mass audiences. The only film that persevered in this harsh economic climate was “Ladies’ Tailor” — it was TV reruns that saved it from oblivion. Even today, it is by far the best-known Soviet Holocaust film.

At the end of 1991, the Soviet Union was dissolved. Along with the state, the entire Soviet film industry ceased to exist. By the early 2000’s, new national film industries gradually came into being, and several Holocaust films were made. But this was not necessarily a cause for celebration as the films were in many instances not much better than those that were made in the Perestroika era.

A Belarussian-German co-production, “Babyn Yar” (dir. Jeff Kanew, 2003), set in occupied Kyiv, is supposed to tell the tragic story of a Jewish family as well as that of their non-Jewish neighbors, but its dramaturgy and unconvincing acting turn it into cheap melodrama. Another “Babyn Yar”, a TV film, made in Ukraine (dir. Nikolai Zaseev-Rudenko, 2002), tells the story of a Jewish woman, a survivor of Babyn Yar, who goes to visit the site of the atrocity many years later. Improbably, in the ravine she encounters a former Nazi who has also come to visit, and the two share a bizarre vision of the Madonna as they partake in bouts of grandiloquence. Predictably, none of these films achieved critical or box-office success.

The events of the Holocaust are reflected in the subplots of several later films, the best of them being the 2004 “Daddy” (“Papa”, dir. Vladimir Mashkov), which is based on a play by the famous Soviet author and song- writer Alexander Galich. The film features a heartbreaking scene of an execution in the Tulchin ghetto. Later, an important novel, “Heavy Sand” by Anatolii Rybakov, was dramatized for TV. The novel was for years one of the very few works of Soviet literature that gave expression to Jewish history and culture. The resulting sixteen-part TV series (2008, dir. Anton Barschevskii) was state-funded and broadcast on the Russian state-owned Channel One, signaling that the new Kremlin regime now sanctioned the representation of the Holocaust (albeit not in Russia). At the center of the epic plot is the life story of a Jewish couple and their offspring, set a town of Snovsk, Ukraine (the actual place where Rybakov spent his childhood). The last episodes depict the horrors of their life in the ghetto, and eventual uprising and escape. Unfortunately, the series represents Jews with idealized simplicity. This idealization revisits the tenets of socialist realism, only now, instead of workers and revolutionaries, Jews are model citizens and exemplary human beings.

All these films differ radically from the ones made during the Soviet era. With the Soviet censorship restrictions removed, these films no longer need to universalize: they can speak openly about the Jewish identity of their characters. Similarly, instead of externalizing the Holocaust, they can locate the events in the Soviet territories; some of them even cautiously address instances of local anti-Semitism and collaboration with the Nazis. At the same time, there are so few films that actually attempt to represent the Holocaust, that one wonders whether the Soviet legacy of silencing continues. This is also part of a larger problem: memory work is still not being carried out to an adequate degree in post-Soviet countries, which includes Ukraine. Despite the bombastic war memorials and official rhetoric about the glorious victory, the memory of WWII and the memory of the Holocaust are not integrated into the educational curriculum or everyday discussions.

But there is potentially hope on the horizon. Several years ago, auteur director Sergei Loznitsa (who grew up in Kyiv and is now based in Germany) started working on a narrative feature based on the Babyn Yar massacre of 1941. A masterful craftsman, Loznitsa has made multiple, prize winning films that have dealt with historical issues relating to the war, including “In The Fog” (2012). Originally, he planned to film on location, in Kyiv. But history interfered, and by the time that he had arrived in the Ukrainian capital in late 2013, the city was already engulfed in protests. Loznitsa set his historical project aside to make a documentary about the remarkable events that he was witnessing. “Maidan” premiered at Cannes to great acclaim. Since then the filmmaker has returned to his original intent, with the current filming planned for 2019. Loznitsa envisions his future film without conventional narrative plot — for him standard dramatic tension is irrelevant when trying to convey massive tragic events. Instead his film will consist of a complex mosaic of scenes represented from various vantage points, including those of Jewish victims, Red Army fighters, Nazi officials, NKVD operators, and local bystanders and collaborators. Instead of a traditional protagonist, all these characters will play their parts in this large-scale production, to be filmed in his unflinching documentarian style. The goal, according to Loznitsa, is to create a sense of having been present at the site and to elicit deeply-felt empathy and personal involvement with the events.

This ambitious and high-budgeted project is still in the midst of seeking European funding, but it has already received support from the state of Ukraine. For Loznitsa, receiving Ukrainian public funding carries symbolic rather that financial weight. The finalization of the project, which would doubtless be a significant film, and its widespread screening in Ukraine and across the post-Soviet world are still in the future. Embracing Loznitsa’s film would constitute the next step in helping Ukraine to deal honestly with its complex and morally fraught past.

Olga Gershenson is Professor of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.