The newly built Podil Theater building has proven to be quite controversial with it’s modernist exterior making many observers quite unhappy. If nothing else, the fiery controversy that has erupted around it after it was opened in last autumn shows that after two decades of ad hoc haphazard construction, Ukrainians are really beginning to care about issues relating to Urbanism.

The world, and consequently our cities, are in a constant state of change. If architecture allows a city to document its past and preserve its cultural character, than one of the greatest challenges in preserving our historical heritage is the task of framing modern accomplishments within the context of existing narratives. This is all the more difficult if one is also keeps in mind the fact that the structures that we will build today will become the historical legacy of future generations.

Today, new ideas, materials and technologies allow architects and designers to create remarkable constructions of astounding shape and form, the sort of objects that could never have been built previously. In contemporary architectural art, it is vital to capture the spirit of the age while also considering a structure’s relationship to history and the impact it would have on the surrounding environment. Livability is as important as aesthetic, and in the process of modernizing our cities, we must be mindful of the risks that come with new constructions breaking the congruity of the urban milieu.

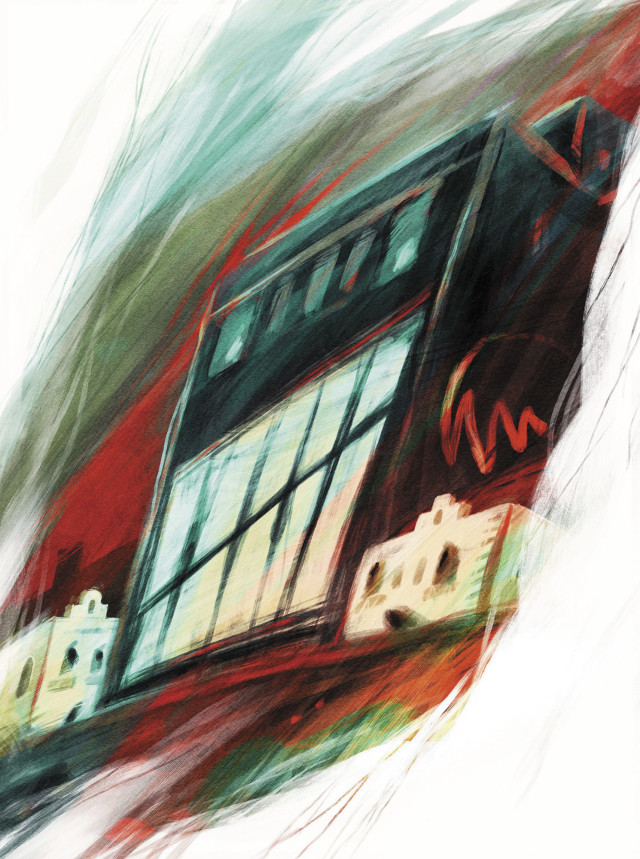

The end of the year 2016 witnessed saw a somewhat negative response of many of Kyiv’s citizens to the opening of the new facade of the Theater on Podil, located on Andriyivskiy Descent. The disappointment in the crowd was palpable, although of course it was not universal. Currently, Ukrainian architecture is drawn towards various forms of historical revival – So it is fair to ask: why wasn’t this reconstruction fully accepted? There are actually a number of reasons why the theater may not fit within the context of its location and its visitors.

First and foremost, we have to remember the historical specifics of this particular urban space. The Andriyivskiy Descent is one of the oldest and most popular landmarks in Kyiv, enriching the cultural life of the capital with its museums, galleries and antique shops. The new theater building clearly stands out from the architectural ensemble it must be said. Indeed, the building almost hangs over the descent, creating a feeling of incongruity rather than a sense of harmony. Architectural balance is achieved through carefully planned order, symmetry and repetition — these aspects have to be infused with creativity and variety to achieve optimal results, bringing harmony and energy to urban spaces.

The most controversial part of the building is the upper half which has been referred to as a “crematorium” or a “shipping container” because of its cubic shape and dark grey, nearly black, matte color. The section appears stiff and heavy, mostly because of the window arrangement and building material. This type of construction is not new in contemporary architecture: the Museu Blau in Barcelona is also based on heavy forms and colors, but it is brightened up by the presence of uneven window placement and the use of reflective materials under the building, which give the structure a finished sensation of lightness and flexibility.

On the subject of building materials, even the bottom section, which is intended to fit in with the pattern of the older buildings around it, seems somewhat incongruous. Perhaps the issue is that the two patterns of the building do not work together. To demonstrate the importance of building materials in design, we can look to the Project Orange building in London —the structure is commonly cited in Ukrainian media as the prototype for the new Theater on Podil. However, the London creation is more successful and appropriate for its context. The bottom portion of Project Orange is made of rustic brick, so there are hints of authenticity which maintain interaction with neighboring structures. The upper part of the construction is made of dark, striped material, creating a sense of movement. The two parts of the building work together because neither has a strict, even pattern, and while the first floor is stable, the second grows rapidly out of the older section, imitating the interaction and connections between past and present. In the Kyiv theater building however, the composition is flat, the two parts conflicting instead of complementing one another.

Certainly, many do not share this impression of the building, and some may have seen something entirely different in the new architectural creation. Moreover, since we haven’t seen the inside design of the Theater yet, there is still hope that it will redeem the construction in the eyes of Kyiv’s guests and residents. Still, first impressions are hard to shake and many have already formed a negative opinion. Perhaps with time we will be able to judge which architectural decisions were prudent and which were not.

We have witnessed buildings like The Dancing House (the Nationale-Niderlanden building) in Prague or The Michael Lee-Chin Crystal of the Royal Ontario Museum — constructions that were not accepted by the citizens or well-received by critics, but which have become essential to the image of their respective cities. However, comparing architectural pieces to each other will not help us understand what Ukrainian urban spaces really need. There is currently a huge opportunity for Ukraine’s major cities to develop new architectural and cultural landmarks that will strengthen Ukraine’s identity while anchoring themselves in the country’s history. The only way to approach this endeavor is with intelligence and respect, a sense of creativity and a love for Ukraine’s land and people.

Masha Sotskaya is a writer living in Odessa.