Marina Tsvetaeva (1982-1941) was one of the great Russian language poets of the 20th century. She was greatly admired by Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky: “Well, if you are talking about the twentieth century, I’ll give you a list of poets. Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva- and she is the greatest one, in my view. The greatest poet in the twentieth century was a woman.”

Mary Jane White is one of her most preeminent translators into the English language.

As I reflect upon my relationship as a reader-translator of Tsvetaeva, I find that as a contemporary American woman who began reading, writing and translating poetry in the early 1970’s, I share a generational point of view with my American contemporary and sister-poet Tess Gallagher as expressed in her introductory essay “Translating the fine excess of spirit in Marina Tsvetaeva”:

“Marina Tsvetaeva holds a very special place in my memory of the search for women writers who might offer examples of what to admire and to which we might aspire. The early 1970’s female models for young women poets like myself, as we began to form our poetic voices, were either hermetic such as Emily Dickinson — who was shuttered away, with her bounty hidden in mason jars because her genius had been thwarted by male publishing predilections — or at the other end of the scale, the explosive cauldron of pent up righteous anger and truth-telling of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton — for which one was grateful, while feeling guiltily that one had perhaps been ritually saved by their suicides from similar psychic trauma.”

My own first early 1970’s introduction to Marina Tsvetaeva came as I was beginning to read and struggling to write poetry in English while also beginning and struggling to learn the rudiments of inflected Russian grammar at Reed College. Tsvetaeva was introduced by a brief selection of facing translations in an anthology of Modern Russian Poetry edited by Vladimir Markov and Merrill Sparks.

I remember that the particular Tsvetaeva poem that struck me as most memorable at the time was “An Attempt at Jealousy.” Where I had ever heard a voice like that? Never!

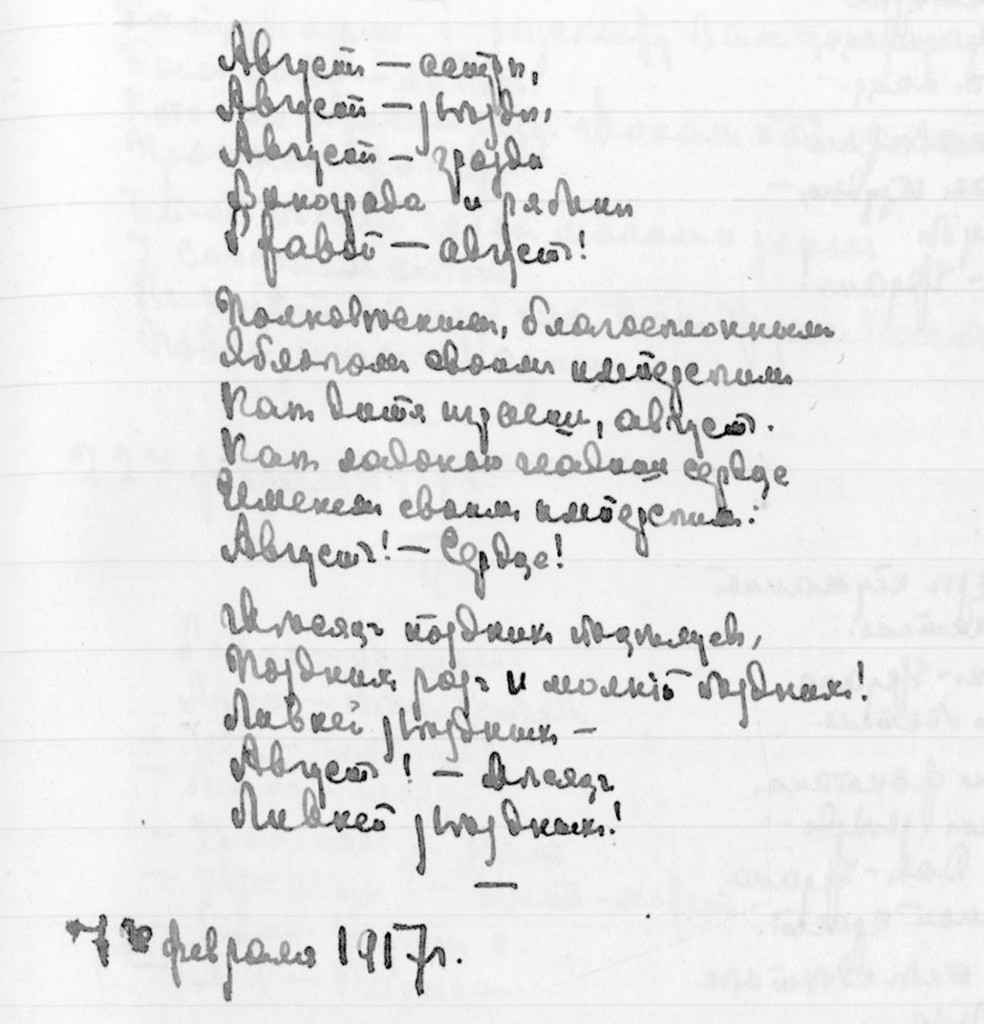

This, now, is my new translation:

An Attempt At Jealousy

(addressed to Mark Slonim)

How is your life with another, —

Simpler, is it? — One stroke of an oar!—

And as easily as some coastline

Your memory of me

Recedes, like a floating island

(In the sky — not the water!)

Souls, souls! should be your sisters,

Not your mistress-—es!

How is your life with a simple

Woman? Without your goddess?

Your Majesty dethroned, over-

Thrown (by a single slip-up),

How is your life — keeping busy —

Holed up? How do you even — get up?

With the customs of undying banality

How do you manage, poor man?

“Enough of these eruptions —

And scenes! I’ll get my own house.”

How is life with just anyone —

My chosen one!

With more appropriate, more edible —

Food? Fed up — not your fault . . .

How is your life with a molehill —

You, who trampled Sinai!

How is your life with a foreigner,

A local? Close to your rib — a dear?

Doesn’t shame lash your head

Like the reins of Zeus?

How is your life — are you well —

Able? Do you sing ever — how?

With the curse of undying conscience

How do you manage, poor man?

How is your life with a commodity

Of the market? Finding her rent — steep?

After the marble of Carrara

How is life with the dust

Of plaster? (A God—hewn from

Blocks — and now utterly shattered!)

How is your life with the hundredth-thousandth —

You, who knew Lilith!

Does your novelty of the market

Satisfy? Grown cool to enchantment,

How is your life with an earthly

Woman, with no sixth

Sense?

Well, I declare: are you happy?

No? In a shallow draining whirl —

How is your life, darling? Is it harder,

As it is for me, with another?

19 November 1924

Here was, as Tess Gallagher described her, “the Tsvetaeva who really wants to love like the gods, not like a mere human being” . . . for whom “it was not easy to find lovers who could soar with her, the Tsvetaeva who “uses her poetry to regain her emotional balance. Instead of cutting a lover off for leaving her, or becoming the victim, she turns the tables on them and lets them feel what they have lost in abandoning their love of her. This was a newly articulated paradigm for women poets all over the world trying to do more than lick wounds in the stance of a victim.”

Later, in the mid-1970’s, as I was writing toward my MFA in Poetry from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and finishing my law degree, I had the opportunity to work a couple of seasons for the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program as an assistant to Directors Paul and Hualing Engle; each week I was handed literal “trots” from various world languages to translate writers’ presentations (on deadline!) into English.

During those rich and busy years at Iowa, I also studied with Russian translators, John Glad and Daniel Weissbort (who with Ted Hughes founded and edited Modern Poetry in Translation), and was able to contribute my own first translations of Russian poems by Nikolay Gumilyov, Vladislav Khodasevich, Vyacheslav Ivanov and Edward Limonov to an anthology that they co-edited called “IRussian Poetry: The Modern Period”, which became a New York Times Notable Book of the Year.

Then, in February of 1978, I turned my attention to translating Tsvetaeva because:

“. . . as an anonymous member of an Iowa City audience I had the opportunity to ask Russian-born poet Joseph Brodsky several questions about Anna Akhmatova — whose reputation remains wider than Tsvetaeva’s. Akhmatova and Brodsky were acquainted in Moscow when she was a very old woman and he a young man. He confessed that they had gossiped, as poets will do, about other poets, but that Akhmatova then ‘was awfully humble. She used to say that ‘in comparison with [Pushkin] and Tsvetaeva I am just a little cow. I am a cow,’ that’s what she used to say.’ I think now of what Tsvetaeva might have given to have been eavesdropping then!

This exchange is in curious accord with Tess Gallagher’s own recent comparative description of the differing appeals of Akhmatova and Tsvetaeva:

“In placing Tsvetaeva’s appeal to American contemporary poetry of the present and myself in the 1970’s, I believe she has been the more dangerous and unwieldy model when compared to Akhmatova, who became so important to us as a sign of stature under political and emotional duress, attracting translators such as Jane Kenyon whose own work was greatly emboldened by Akhmatova.”

Brodsky’s direct answers to my questions-from-the-floor raised in me an early ambition to write a Tsvetaeva in English that would serve me and the next generation of American poets with a translation that would let Tsvetaeva “wear fully the stature of the English she might have given us, had she written in English.”

Since 1978, I’ve continued to work on reading and translating Tsvetaeva, and thus taking Brodsky’s answers as a sort of assignment, for nearly forty years. On weekdays and court days I carried my thrice-re-bound Oxford Russian-English Dictionary and little red moleskin notebooks from courthouse to courthouse throughout the five counties of Northeast Iowa, working in fits and starts while waiting for my assigned legal hearings and cases to be called —- trial law being not unlike war in that they both respected the maxim of “hurry up, and wait”.

What you do during the wait is another life . . . and what a great privilege is has been to try to translate Tsvetaeva! So, the translation included here arose, was thrown off, as the residue of my own reading. I trust that the residue of my reading — as one poet hoping to read another — is the gift to my readers in English, who might otherwise have no opportunity of coming to hear anything of Tsvetaeva’s own (still hidden) Russian voice.

Mary Jane White holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She is the recipient of NEA Fellowships in both poetry and translation. She has published numerous books of Tsvetaeva translations which include “Starry Sky to Starry Sky” (1988) “New Year’s, an elegy for Rilke” and “Poem of the Hill”.