First I had dealings with Benya Krik, then with Lyubka Shneyveys. Do these words mean anything to you? Do they leave a taste in your mouth? The only thing I dodged on this trail of death was Seryozha Utochkin. Him I didn’t run across — and so I’m still alive. He straddles the city, this Utochkin, like a bronze monument, with his red hair and grey eyes. And all of us have to scurry between his legs.

…But let’s not take the story down side streets, even if these side streets happen to be lined with blooming acacias and ripening chestnuts. First about Benya, then about Lyubka Shneyveys. That’ll be the end of it. And everyone will be satisfied, because the period is just where it ought to be.

…I became a broker. When I became a broker in Odessa, I grew leaves, sprouted shoots. Weighed down with these shoots, I felt miserable. Why? Competition is why. If it weren’t for competition, I wouldn’t even blow my nose on justice. There’s no craft, no skill in my hands. I have nothing but air in front of me. It shines like the sea on a sunny day, this beautiful, empty air. But the shoots want to eat. I’ve got seven of them, and my wife is the eighth. No, I didn’t blow my nose on justice. Justice blew its nose on me. Why? Competition is why.

It was a co-operative store, called “Justice.” You can’t say there was anything wrong with it. To say that there was something wrong, that would be a sin. It had six partners behind it, all primo de primo, and all experts in their particular rackets. The shop was full of merchandise, and the police had put Motya from Golovkovskaya Street out front to guard the place. What more do you need? Seems to me, you couldn’t ask for more. It was the bookkeeper from “Justice” who offered me the deal. Word of honour — a sure deal, a quiet deal. I gave my body a once-over with a clothes brush and took it over to Benya. The King made out like he didn’t notice my body. So I cleared my throat and said:

“Here’s the deal, Benya.”

The King was having a bite: a decanter of vodka, a fat cigar, a wife with a belly — in her seventh or eighth month, hard to say. And all around the terrace: nature and wild grape vines.

“Here’s the deal, Benya,” I say.

“When?” he asks.

“Well, since you ask,” I say to the King, “I’ve got to give you my opinion. In my opinion, it’s best to do it on Saturday night. And by the way, the fellow on guard is none other than Motya from Golovkovskaya Street. Sure, you could do it on a weekday, but why turn such a quiet affair into a loud one?”

Such was my opinion. And the King’s wife agreed with me.

“Baby doll,” Benya says to her then, “go rest up on the sofa.”

Then he peels the gold band off his cigar with slow fingers and turns to Froim Shtern:

“Tell me, Rook, are we busy on Saturday, or are we not busy on Saturday?”

But Froim Shtern, he’s always looking out for number one. He’s a red-headed man, with only one eye on his head. Froim Shtern isn’t about to give a straight answer.

“On Saturday,” he says, “you promised to pay a visit to the Mutual Credit Society…”

The Rook pretends he’s got nothing more to say and points his one eye at the farthest corner of the terrace, cool as a cucumber.

“Good,” Benya Krik shoots back. “You remind me of Tsudechkis on Saturday, Rook. Make a note of it.” Then the King turns to me and says, “You get back to your family, Tsudechkis. There’s a good chance I’ll stop by ‘Justice’ on Saturday. Take my words with you, Tsudechkis, and get walking.”

The King doesn’t talk much, and he talks politely. This puts such a scare in people that they never ask him to explain or repeat himself. I left the courtyard, set off down Gospitalnaya Street, turned down Stepovaya, then stopped to weigh Benya’s words. I hefted them, fingered them, held them between my front teeth — and I saw that these weren’t at all the words I needed.

“There’s a good chance,” the King had said, peeling the gold band off his cigars with slow fingers. The King doesn’t talk much, and he talks politely. Who can penetrate the meaning of the King’s few words? There’s a good chance I’ll stop by — or there’s a good chance I won’t? Between yes and no hangs a five-thousand-rouble commission. Without even counting the two cows I keep for my needs, I’ve got nine mouths that are always ready to eat. Who gave me the right to take risks? Who’s to say that the bookkeeper from “Justice” didn’t pay a visit to Buntselman right after coming to me? And then Buntselman could have turned right around and run to Kolka the Pin. And that Kolka, he’s one hot-blooded fellow. The King’s words fell like a mound of boulders onto the path where nine-headed hunger roved. Simply put, I gave Buntselman a little warning. He was coming in to see Kolka just as I was leaving. It was hot, and he was sweating. “Hold your horses, Buntselman,” I warned him. “No point rushing, and no point working up a sweat. This is where I take my meals. Und damit Punktum, as the Germans say.”

And the fifth day passed. And the sixth day passed. Saturday strolled the streets of Moldavanka. Motya was already at his post, I was sound asleep in my bed, and Kolka was at work in “Justice.” He’d already loaded half a dray and was planning on loading another half. Suddenly, a clatter broke out in the alley, the rattling of iron-bound wheels. Motya from Golovkovskaya Street grabbed hold of a telegraph pole and asked, “Should I drop it?”

Kolka answered, “Not yet.”

(This pole, see, could be dropped, if the situation demanded it.)

The cart rolled into the alley at a walk and pulled up at the shop. Kolka realized it was the police, and his heart went to pieces, because he hated to leave a job half-done.

“Motya,” he said, “when you hear me fire, the pole drops.”

“You got it,” said Motya.

The Pin went back into the shop with his crew. They lined up against the wall and pulled out their revolvers. Ten eyes and five revolvers were fixed on the door, to say nothing of the sawn-off telegraph pole. The youngsters were full of anticipation.

“Buzz off, coppers,” one of the impatient fellows whispered. “Buzz off or we’ll flatten you…”

“Shut it,” Benya Krik commanded, jumping down from the mezzanine. “What coppers, you mug? The King has arrived.”

Had this gone on a bit longer, all hell would have broken loose. Benya knocked the Pin to the ground and grabbed his revolver. Men began to drop down from the mezzanine like rain. You couldn’t make anything out in the dark.

“I see how it is!” Kolka shouted. “Benya wants to do me in. Now there’s an interesting development…”

For the first time in the King’s life, he’d been mistaken for a cop. That was a laugh. The gangsters cracked up. They lit their torches, busted their guts and rolled on the floor, choking with laughter.

But the King, he wasn’t laughing.

“Across Odessa, they’ll say,” he began in a serious tone, “they’ll say the King was tempted by his friend’s take.”

“They’ll say it once,” the Pin replied. “No one who says it once will get the chance to say it twice.”

“Kolka,” the King went on in his calm, solemn tone. “Do you believe me, Kolka?”

And then the gangsters stopped laughing. They all had torches burning in their hands, but the laughter had crept out of “Justice.”

“Believe you about what, King?”

“Do you believe me, Kolka, when I say I had nothing to do with this?”

And he sat down, this crestfallen king, covered his eyes with a dusty sleeve and shed tears. Such was the pride of this man, may he burn. And all the gangsters, every one of them, saw their king crying on account of his wounded pride.

Then they stood in front of each other. Benya stood, and the Pin stood. They began making amends, they apologized, they kissed each other on the lips, and they shook each other’s hands with such force that it looked as if they wanted to tear them clean off. By the time dawn began blinking its bleary eyes, Motya’s shift had ended and he’d gone back to the station, and two full drays had carted off what had been known as the co-operative shop “Justice,” while the King and Kolka were still grieving, still bowing, and, throwing their arms around each other’s necks, kissing tenderly, like a couple of drunks.

And who was fate after that morning? It was after me, Tsudechkis, and it found me.

“Kolka,” the King finally asks, “who gave you the lowdown on ‘Justice’?”

“Tsudechkis. And you, Benya—how’d you get it?” “Tsudechkis.”

“Benya!” Kolka cried out. “Are we gonna leave him among the living?”

“Certainly not,” Benya says, and turns to one-eyed Shtern, who’s chortling in the corner — because Shtern and I, we don’t get along. “Froim,” he says, “order a brocaded coffin. I’m heading for Tsudechkis. And Kolka, when a man starts something, he’s got to finish it, so I ask you kindly, on behalf of me and my wife, come and see us in the morning, have a bite in my family circle.”

At around five in the morning, no, around four, or maybe it wasn’t even four yet, the King marched into my bedroom, picked me up off the bed, you’ll excuse me, by my back, put me down on the floor, and placed his foot on my nose. Hearing various sounds and the like, my wife jumped out of bed and asked Benya:

“Monsieur Krik, what’s my Tsudechkis done to you?”

“What do you mean, what?” asked Benya, never taking his foot off the bridge of my nose, and then tears fell from his eyes. “He cast a shadow over my name, shamed me in front of my friends. You can say your goodbyes to him, Madame Tsudechkis, because my honour is dearer to me than happiness. He will not remain among the living…”

He kept on crying and stomping on me. My wife saw how much this upset me and commenced screaming. She started at half past four and didn’t finish till eight. And how she gave it to him, oy, how she gave it to him! You should have seen it!

“Why are you cross with my Tsudechkis?” she screamed, standing on the bed, and I, writhing on the floor, stared up at her with admiration. “Why are you beating my Tsudechkis? Because he tried to feed nine hungry nestlings? You’re a big so-and-so, aren’t you, King? Son-in-law of a rich man, and rich yourself, and your father’s flush too! The world’s your oyster! What’s one bungled deal to Benchik, when next week will bring him seven successes? Don’t you dare beat my Tsudechkis! Don’t you dare!”

She saved my life.

When the children woke up they started screaming along with my wife. Benya finally ruined my health to the degree that he felt it should be ruined. He put up two hundred roubles for my medical bills and left. I was taken to the Jewish Hospital. On Sunday I was at death’s door, on Monday I was on the mend, and on Tuesday things could have gone either way.

That’s my first story. Who’s to blame, and why? Is Benya really to blame? Let’s not throw dust in each other’s eyes. There’s no one else in the world like Benya the King. He cuts through lies and looks for justice, be it justice in quotes or without them. While everyone else, they’re as calm as clams. They can’t be bothered with justice, won’t go looking for it—and that’s worse.

I recovered. Yes, I slipped out of Benya’s hands — and fell right into Lyubka’s. First about Benya, then about Lyubka Shneyveys. That’ll be the end of it. And everyone will be satisfied, because the period is just where it ought to be.

Translation by Boris Dralyuk

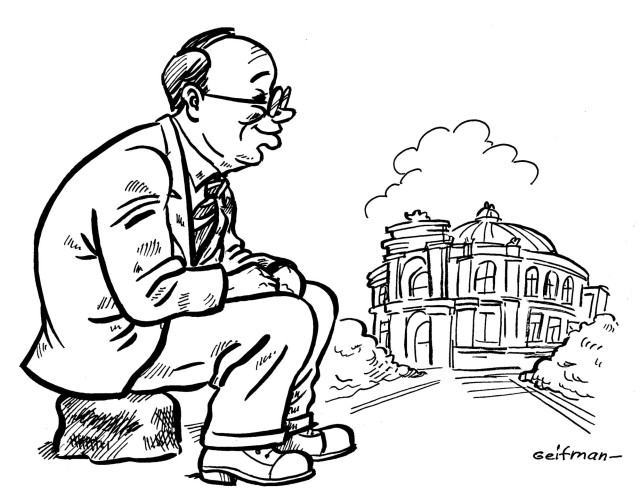

Boris Dralyuk is the Executive Editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books as well as a literary translator. He holds a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures from UCLA, where he taught Russian literature for a number of years. He has also taught at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. He is the author of “Western Crime Fiction Goes East: The Russian Pinkerton Craze 1907-1934” and translator of several volumes from Russian and Polish, including, most recently, Isaac Babel’s “Red Cavalry” and “Odessa Stories” published by Pushkin Press. He is also the editor of “1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution,” and co-editor, with Robert Chandler and Irina Mashinski, of “The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry.” He is widely considered to be one of the main scholars on the life and work of Isaac Babel.

Dralyuk is very fond of one the Odessa Tales in particular:

“‘Justice in Quotes,’ written in the voice of Tsudechkis, the Odessa broker who plays a major part in ‘Lyubka the Cossack,’ was published in an Odessa newspaper in August 1921, two months after ‘The King’ appeared in another Odessa newspaper, but the story may have been written before ‘The King.’ Babel never republished ‘Justice’ with the Odessa cycle, likely because it’s narrated entirely by Tsudechkis. Yet it’s precisely the unmistakable voices of folks like Tsudechkis that had lured Babel back to Moldavanka in the first place, and that make the Odessa stories spring to life. ‘Justice in Quotes’ may be a practice run, but it’s certainly not a dry one.”