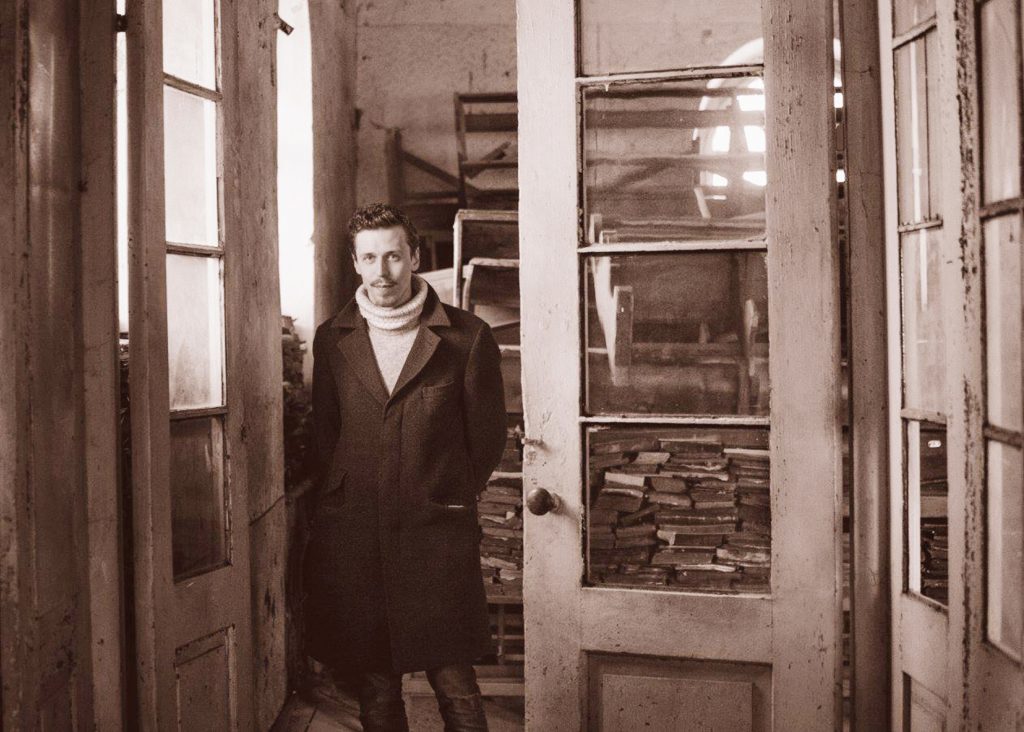

Ukrainian Director Ivan Orlenko On His Debute Film “In Our Synagogue”.

“In Our Synagogue” is the first film by Ukrainian director Ivan Orlenko. The 30-minute, black-and-white short is based on Franz Kafka’s unfinished short story of the same name. Of the the film’s total budget of just over 1.5 million UAH (roughly $56 thousand), almost two thirds were provided by the Ukrainian state. The film tells the story of a 12-year-old Jewish boy trying to catch a mysterious animal that lives in the synagogue. Legend has it that the creature has been living there for several generations. Whether it has always been the same animal or not is unknown. The mystical creature would have been forgotten long ago if not for the women: they scream whenever they see the animal, breaking the silence during prayer. Trying to catch the animal, the boy plunges into a tangle of conflicting stories told by different people.

Kyiv-based journalist Olesya Anastasieva spoke with Orlenko about his feature film.

Odessa Review (Olesya Anastasieva): Why did you decide to make a film based on a work by Kafka?

Ivan Orlenko (IO): I find it difficult to reduce it to just one reason. First, it is Kafka’s work. It is an incredible piece of literature itself, which in my opinion has not fully found its on-screen portrayal. I found this unfinished story in Kafka’s notebooks by accident… I came up with the idea of putting this parable into a completely different context, so that breaking the narrative was the only possible and right way to go about things. There are things that are not spoken about. My approach was not to add to Kafka’s parable, but to build a world around it that lives by its own rules, generating asynchronous interactions and special allusions, such as a conversation between the blind and the deaf or different atonal music themes. Kafka’s original source is one and a half pages long, while the script is about twenty. In my opinion, such adjustments are adequate to the modern sense of the world with our absurd, postmodern counterpoints.

[…]

But “In Our Synagogue” is one of the few of Kafka’s texts that directly addresses the Jewish culture, the religion of his ancestors, which Kafka had little to do with.

Ukraine was the motherland of and home to millions of Jews. However, now only a few preserved old synagogues and neglected ancient cemeteries are left. Yiddish, the former mother tongue of millions can no longer be heard, except for some elders who still remember the “mameloshn’” [“mother tongue”]. This picture of the devastation, the forgotten world made me shoot the film not only in Yiddish, but inside the old synagogue and some miraculously surviving Jewish houses, with the painful knowledge that all of these buildings will soon collapse, and grass will grow over them, because no one lives there. It is this sense of a long lost time that predetermined that maximum attention would be drawn to the signs of that times, language, and everyday life. Time running indifferently and inexorably, only sometimes allowing the story to finish, is probably what my film is about, although it’s not for me to judge what it is.

If we look at the movie from a purely pragmatic point of view, as something that has a meaning and is valuable, then we can say that my film just shows once again what beauty there is in Ukraine. But this beauty is disappearing, and soon it will completely disappear if the people responsible for the preservation of historical buildings will continue to remain inactive.

OR: You found your own style to tell Kafka’s story. Who worked with you on the script? And tell me, why did you decide to make the film in Yiddish?

IO: I wrote the script myself. Michael Felsenbaum translated the dialogues into Yiddish. The film was filmed in Yiddish, because at that time and place in which the film is set, it was impossible for the characters to speak another language.

OR: But you must agree, that to write a text in a language that few people now speak is one thing. It is quite another to make sure that the actors on the set could speak it freely. So tell me, how proficiently did everyone who took part in the movie speak this language? And about the cast, tell me: Is everyone in the movie a professional actor?

IO: I tried to have as few professional actors as possible. Talented theater actors who can act on a film set do not exist. And this is a huge problem. It is not taught anywhere in Ukraine (although they graduated with the diploma “actor of theater and cinema”). A person who does not have experience being in front of a camera will not understand that instead of whispering in someone else’s ear he is yelling into a megaphone, figuratively speaking. […] We had to find people who were not only talented actors but also had a talent for languages. Therefore, in the whole film, only a few roles are performed by professional actors, the rest are native speakers and they helped the actors very much, did a great job with the text and pronunciations, for which I am infinitely grateful.

We filmed on location in Zakarpattia and a huge part of the people I wanted to shoot, I simply could not afford to take [on]. Native speakers are now mainly Hasidic [Jews] who do not watch TV, do not go to the movies, and it was very difficult to get them on set. Also I had a specialist on the language and pronunciation, an excellent writer and now actor Michael Felsenbaum. All the older people who starred in the film spoke the language. While working on the film, they tried to dissuade me, saying: “Who will watch it? Who will understand?”

OR: Where did you find the locations for the film? In particular, that pristine street without glass balconies or satellite dishes?

IO: There were little bits of various places. The synagogue itself and several streets are located in the city of Khust in the Zakarpattia region. Two interiors we found in Kyiv, another street is in Mukachevo (there on the horizon you can see the “Palanok” castle as an allusion to the “Castle” of Kafka). Part of the shooting took place in France, in Strasbourg, where we filmed footage in a school and the ritual mikvah. There were several options for where to shoot the film, because in Ukraine, there are still several remaining authentic synagogues — Shargorod, Bershad, Berdichev. But when I arrived in Khust, I immediately realized that I would only shoot there. The architecture is just incredible, I’m very glad that we were allowed to shoot inside of it. By the way, this is the only pre-war synagogue that never closed down, neither during the war nor after the USSR. This synagogue itself has a very interesting story. I think that I will shoot some more movies there.

OR: What will your new film be about?

IO: We are working on a new project with the Ukrainian producer Valery Kalmykov.

I’m writing a script for a feature film about a group of [Nazi-era] German filmmakers who shot a movie in the [Jewish] ghetto. This story is based on real events, and I want to combine the footage they shot there with a look at them in the film. This combination is really difficult to realize technically. For the main role, we found the remarkable German actor Jacob Dil, who starred in Andrei Konchalovsky’s “Paradise” and Alexander Mindadze’s “Dear Hans, dear Peter”. This is our first choice and I am not even considering any other options. The script is written for real people, sometimes personal experience can bring another dimension to the film and the story changes in an unexpected way.

In the film, I don’t want to give a glance from the outside, but a look from the inside, from the womb. This is a story about a small man with ambitions, a professional in his business who is simply brought to some place in this ghetto and he shoots there. And this footage, just like “The Eternal Jew” and similar Nazi propaganda films, gets into people’s minds and provokes hatred that ends with lives being taken. It is about the power of the visual image, how it is used to get ideologies into people’s heads and about what this ideology does to people, in brief.

In order to develop the project we are now looking for funding. We want to do an expedition to look inside the archives, explore the locations, inspect all the materials, etc.

Producing this film will be expensive and we will definitely look for co-producers abroad — Poland, the Czech Republic, Germany.

OR: Is it important to you to simply study that historical period or do you find parallels between what happened then and what is happening today?

IO: The past can not be exclusively the past. I think both. For me, the distance, time- and cultural-wise, is important but the parallels are quite obvious. Let’s take the 90’s in Cambodia, Kosovo, Rwanda — nothing changes, and it’s scary. It’s just that the period of the late 30’s and 40’s has already left its mark, it’s more interesting to work with it because there is a certain image that needs to be destroyed. That is already an act of deconstruction, after which the actual history begins. And if we look at what is happening in Russia right now, we will understand that the topic of propaganda is still relevant. What I want to show in my film is that one’s consciousness will determine one’s reality. I think that the parallels are obvious.

Olesya Anastasieva is a journalist living in Kyiv.