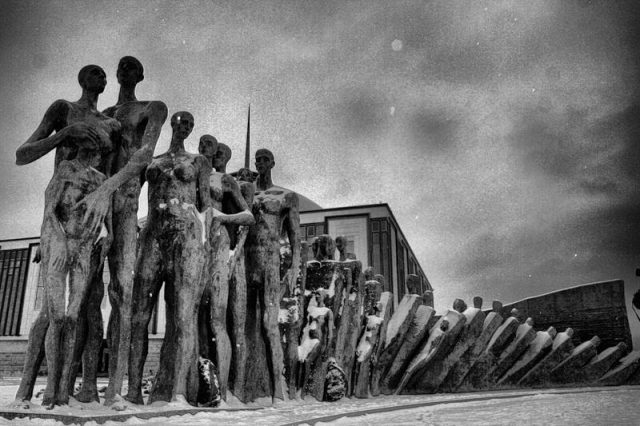

The Soviet authorities didn’t want their own historical narrative to face competition. That meant obliterating memory, rebuilding historical narratives, and suppressing literature.

This article was translated from Ukrainian by Larissa Babij.

After World War II, the Soviet Union entered into two ideological struggles. The first was against remembrance of Eastern European Jews’ fate during the German occupation. The second was against so-called “Bourgeois nationalism”.

However, in reality, both of these policies were part of the same Soviet struggle against nationalism. In the USSR, we see a what Paul Ricœur called “organized forgetting” transformed into a state policy. The Soviet cultivation of its own interpretation of historical memory aimed to conceal the joint Nazi-Soviet responsibility for instigating the war; to hide its crimes against its own citizens and those of other states; and to replace the memories of individuals and communities with the narrative of the new imagined community — the Soviet people.

In both the Jewish and Ukrainian cases, the Soviets moved to destroy the institutional and individual memory-bearers. Examples include the dissolution of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, the only representative body for Jews in the USSR, and the execution of its most prominent members. The USSR also liquidated the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and destroyed members of the clergy.

It deported en masse members of the intelligenstia from the Union’s western territories. In all these cases, any attempts at recollection were considered attempts to resist the official narrative and to advance an opposing narrative based upon other values. “Nationalists” — whether Jewish or Ukrainian — were the main threat to the Communist monopoly on power, memory, and truth.

The Official Narrative

Creating a common narrative of the “Great Patriotic War” (the Soviet name for World War II) that would unite all the peoples of the USSR meant fighting other competing national narratives. According to this black- and-white formula, the “Great Patriotic War” was a heroic stand against Nazism, the common cause of the united Soviet people, and the leader in this struggle was, naturally, the Russian people. Sympathy for the civilian population was beyond consideration; the authorities were suspicious of everyone who lived through the Nazi occupation, including the few surviving Jews. Ostarbeiters (forced laborers for the Nazis), returning prisoners of war, and concentration camp survivors were a priori suspected of disloyalty to the Soviet regime.

After the war, the Soviet authorities took up the task of “cleansing” society of “suspicious” elements. The authorities and secret police conducted systematic and meticulous investigations of the activities of their citizens during the occupation. Those imprisoned by the Nazis had to pass through filtration camp designed by the NKVD (Soviet secret police) before repatriation to the USSR.

The pre-war terror returned in postwar conditions. The struggle against “nationalists” was combined with the trials of Nazis and their collaborators. The policy toward Western Ukraine was especially harsh. The initial struggle was against the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), but by the end of 1945 the entire Ukrainian Galician intelligentsia was targeted, accused of aiding the Ukrainian underground resistance.

After the war, Stalin used Soviet nationalities policy to essentially return the pre-revolutionary order: to subordinate all the nationalities to the “great Russian people”. This required obliterating the memory of the victims on occupied territory. The Soviet Union used three methods to achieve this. First, it erased the nationalities of the Nazis’ victims by referring to them as “peaceful Soviet citizens”. Second, all participants in non-Soviet underground movements were included in the category of “fascist collaborators”. Third and most importantly, the Russian people were declared the main victor in the fight against fascism and the leader of the USSR.

Generalizing the Nazi victims’ backgrounds served a dual purpose: it imposed the idea of a unified whole — the Soviet people — and simultaneously concealed the real picture — at least a third of the civilian victims (in the Ukrainian territories) were Jews. The Soviet authorities’ believed that recognizing the tragedy of the Jewish people as a unique phenomenon would encourage the development of Jewish nationalism. Until the USSR’s end, the very idea of the Holocaust was largely forbidden, and Zionism was placed in the same category as Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism.

The Soviet policy of accusing all non-Soviet underground movements on the occupied territories of collaboration with the Nazis and treating all residents of those territories as suspect also had a political purpose. The authorities were distinctly fearful of minority national movements. When the Soviet secret services learned of attempts at cooperation between Jewish and Ukrainian organizations abroad, they immediately began planning a counter strike aimed at compromising the entire Ukrainian movement. The image of the “Ukrainian nationalist” as a fascist collaborator, one of the most entrenched stereotypes in the Soviet Union and beyond, was the result. It overshadowed the genuine culpability of those who collaborated with the Nazis, especially in the massacre of Jews, by substituting a mythical picture of the “Nazi accomplice”, who could be anybody accused by the authorities of nationalism. In 1944, the main enemies of Soviet power in Galicia were “Polish nationalists”, who were also accused of collaboration with the Germans. But by 1945, the main target had become “Ukrainian nationalists”.

The Soviet leadership also strove to suppress minority nationalism by crediting the victory over Nazism to the Russian people alone. That meant all the other peoples of the USSR, and even the world, had the Russians to thank for peace. By making the Russians heroes, the Soviet Union strove to devalue the struggle of other peoples against Nazism.

Efforts to regulate information about the fate of the Jews in the occupied territories began well before the German invasion. In accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed on September 28, 1939, both the Nazi and Soviet sides pledged to suppress propaganda that was hostile to the other party. In particular, this meant that information about the establishment of ghettos and the mass murder of Jews was prohibited throughout the entire USSR. The results of this policy are obvious, although we will never know to what extent this increased the number of Jewish victims.

The Literary Front

The fates of two books illustrate how attempts to describe the horrors of the war from the civilian population’s point of view were treated. Stalin publicly condemned Ukrainian filmmaker and writer Oleksandr Dovzhenko and even the main characters of his novel “Ukraine in Flames”. The Soviet Union treated the book as if it was written specifically to state that the Soviet Union found itself unprepared for war. One of the main criticisms was that Dovzhenko allegedly failed to label Ukrainian nationalists “traitors” and “fascist accomplices”. In reality, however, the author did not even mention them. Stalin called this work “an open affront to party policy”, and the author quickly understood that “the truth about the people and their calamity” is not needed. In fact, “nothing is needed, except a panegyric”.

“The Black Book”, which Jewish writers Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman began compiling for publication in 1943, was used as evidence during the Nuremberg Trials in 1945-1946. But numerous obstacles prevented its publication in Russian. Then, in 1948, the manuscript was destroyed. Twenty-seven volumes of materials, which formed the basis of this book, ended up in the archive of the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs. In the 1960’s, when a number of literary works dedicated to the mass murder of Jews appeared in print — particularly Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s well-known poem “Babi Yar” and Anatoly Kuznetsov’s novel documenting the same tragic event — Ilya Ehrenburg unsuccessfully attempted to get “The Black Book” published.

From the outset of World War II, the Soviet Union regulated information. For tactical reasons, during the Nuremberg Trials, Soviet censorship bureau GlavLit allowed publications about Nazi crimes. But this did not last long. The final moment under Stalin’s rule when it was possible to tell roughly the truth about the Holocaust was 1945. That year, several works dedicated to the murder of the Jews of western Ukraine were published in Lviv: Olga Duchyminska’s story “Ettie”, Vladimir Belyaev’s novel “Light in Darkness”, and the short story “The Only One in Town” by Yikhyl Falikman.

Each publication has an interesting history, but Duchyminska’s tale deserves particular attention. It’s fate — like that of it’s author — demonstrates the connection between the fight against memory and the struggle against Ukrainian nationalism. “Ettie” was Duchyminska’s first book after the war and the last during her lifetime. A year after its publication, a scathing critique accused the author of distorting the image of the war and raised doubts about the story’s right to be published at all.

Olga Duchyminska was a master of psychological women’s prose. Most of her stories are based on her rich life experience. In the first extensive biography of the author, Roman Horak writes that she provided assistance to the Jews during the war. There is little doubt that “Ettie” is not an artistic invention, but a work based on realities the author knew well. It focuses on the most dramatic event of the German occupation: the liquidation of the Lviv ghetto, or more precisely, the massacre of all those who remained and the hunt for survivors.

The author portrays the state of mind of a woman doomed to death, who explains her own instinct to survive as a maternal instinct. The story, told in the third person, is set in an atmosphere of all-encompassing fear that does not permit one to dare rescue a neighbor. The horrors of the Holocaust are depicted in only a few strokes, but they show the reader much more than other literature of that time. Duchyminska even depicts the attitudes of Lviv’s residents to the murder of the Jews: indifference, fear, and the desire to profit from another’s misfortune. Hardly any other work of Ukrainian literature has portrayed the Holocaust with such authenticity and artistry.

The cruelty of the Nazis is left behind the scenes, but the story is constructed to leave no doubt as to who the heroine is running and hiding from. She is a Jewish woman who miraculously escaped from the burning ghetto and first seeks shelter in Lviv. When she is refused, she makes her way to a village on the outskirts of the city. Her last hope is a teacher who lives there, her old acquaintance. But even the teacher, overwhelmed by fear for her own life, asks the woman to leave her home. The heroine Ettie wanders through the fields for a long time and eventually, barely alive, ends up again at the teacher’s door. The unnamed woman takes Ettie in, hoping that when she gets well, she’ll leave the house and so will the fear.

Of course, this hope is futile. The heroine is consumed with one thought: to survive, so that after the war she can find her children, whom she had sent to her parents in the Volyn region. Despite the circumstances, Ettie survives. After the arrival of the Red Army she ends up in Lviv, wandering the territory of the ghetto, hearing the voices of her children. She is overwhelmed by a sense of the futility of her own existence.

The author obviously chose to end the story that way. But, in print, a few sentences — clearly required by the Soviet publisher — were added after the final scene: the heroine sets off toward her new life in her native Volyn. This artificial ending was evident to both readers and Soviet critics. In a review published in November 1946, critic Mykhailo Parkhomenko lambasted the author for “choosing a person ‘lowly in spirit’ [as the heroine] and thus greatly impoverishing her artistic idea”. Parkhomenko upbraided the heroine for not joining the pro-Soviet partisans, as she “did not live with the feeling that united the people — hatred for the enemy”. Parkhomenko’s final conclusion was ruinous: “The instinct for survival destroyed everything that was truly human in Ettie, and…this denies her the right to be the heroine of the story”.

This was a heavy verdict for Duchyminska not only as a writer (she never again published a literary work), but also as a representative of the Galician intelligentsia, to which the Soviet authorities a priori imputed nationalism. At the same time, it was also a verdict against the subject matter: the destruction of the region’s Jews during the German occupation. From then on, no texts addressing the tragedy of the Holocaust were printed by any publishing house in the Ukrainian republic.

Three years later, 66-year-old Olga Duchyminska was arrested, charged with complicity in the murder of writer Yaroslav Halan. She received the standard sentence — 25 years in the camps — with an equally standard formulation: Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism. Her story shows the intricate connections between the fight against the memory of the Holocaust and the fight against nationalism (Ukrainian and Jewish).

Duchyminska’s story may seem unique and singular, but it demonstrates a general tendency: the memories of World War II, of Hitler’s victims, and of the resistance movements were all repressed. The Soviet authorities’ goal was for its new heroic narrative — along with its main hero, the Russian people — not to face competition.

Ola Hnatiuk is a Professor at the Center for East European Studies, University of Warsaw and at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy.