In the aftermath of the Euromaidan movement, a wave of designers and retailers has come to the fore, ready to meet the needs of patriotic young Ukrainians determined to shop local. Dan Peleschuk asks whether fashion can help drag the country closer to the West. This article previously appeared online in The Calvert Journal.

You probably wouldn’t know it, but Ukraine’s pro-democratic revolution never quite disappeared from the streets of Kyiv — it’s just taken a different form. Alongside its political reboot, the country has been searching for new sources of national pride. For the fashion world, it’s all about Made in Ukraine: a grassroots movement comprised of local designers and producers helping to establish Ukraine as a new outpost of fashion in the East.

On charming, cobblestone streets and sweeping, Soviet-style boulevards across the country, local brands are both benefitting from and contributing to a burgeoning sense of patriotism. They’re putting the country on the map while also helping to build a more stable business climate at home.

Ukraine already boasts some big names in the industry. Vita Kin, for example, has been credited with popularizing “folk fashion” on the catwalks of Western capitals through her contemporary take on the Ukrainian vyshyvanka, or traditional embroidered shirt. But primarily, it’s the constellation of smaller, up-and-coming producers that’s playing a disproportionate role in creating a new kind of “cool” in Ukraine and promoting it abroad.

Somewhat ironically, they can thank the country’s recent troubles for their growth: the war against Moscow-backed separatists sparked a wave of patriotism that encouraged Ukrainians to buy locally across many industries. The sharp economic downturn, meanwhile, slashed their budgets and put more expensive foreign brands out of reach.

Take Kyiv-based designer Elena Pavlenko: only two years ago, the former TV director was putting out small runs of her thick knit accessories “just for fun”. Today, her brand, Pavlenki Workshop, receives orders from countries like Austria, Finland, Switzerland and even the United Arab Emirates, in addition to doing brisk business at home in Ukraine. Now she’s eyeing potential retail partnerships in Western Europe.

In most developing democracies, small- and medium-sized businesses typically take the lead in building modern economies and healthy business cultures. In Ukraine, that sort of culture is still in its infancy, but local producers are helping lay the foundation. Much more than mimicking Western fashion or cultural trends, Made in Ukraine is hoping to embody the fundamental elements of Western-style business: robust growth, transparency, and competition. That’s why the movement is something of a training course for budding designers and producers as well as the Ukrainian economy writ large.

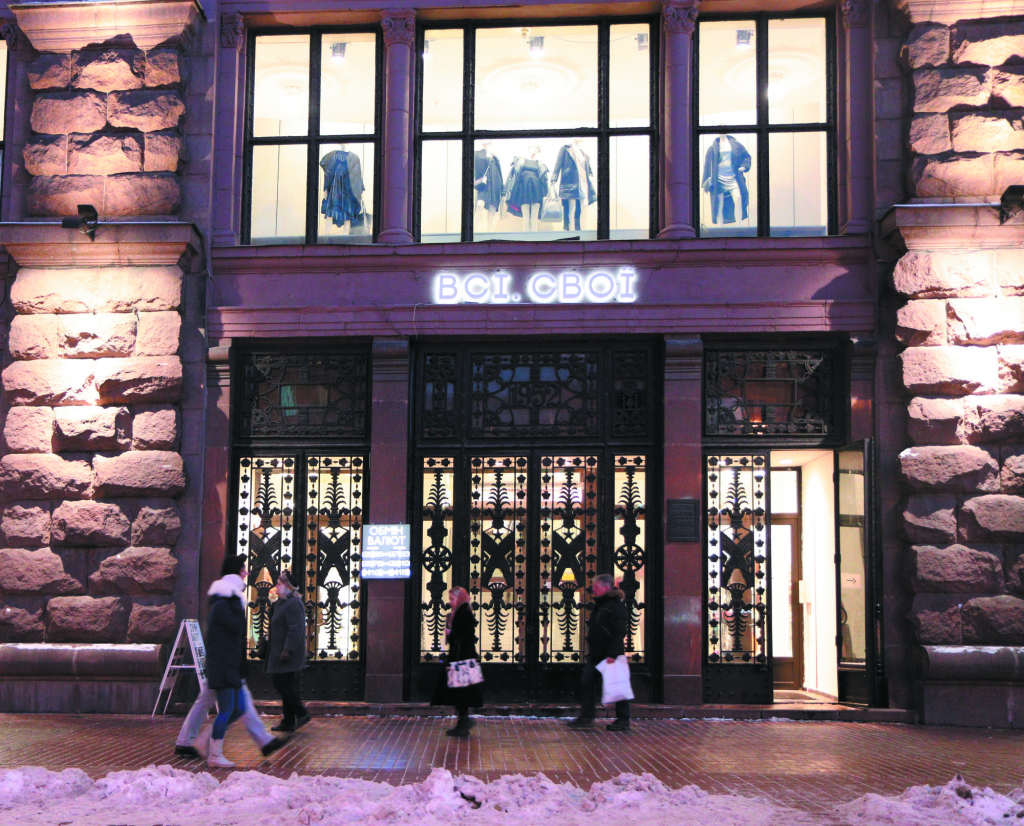

Last autumn, the country’s largest Made in Ukraine store opened a flagship location on Kyiv’s main drag, offering a one-stop shop for anyone interested in Ukrainian-made apparel and accessories. Vsi Svoyi, which roughly translates to “All Our Own”, brings together several hundred brands from showrooms and basement boutiques across the country. The goal, says store director Anna Lukovkina, is for Ukrainian brands to become the new normal for local consumers — that is, for people to not even think about the fact they’re “buying Ukrainian”. She also hopes it will eventually turn Ukraine into a prime destination for fashion fanatics from Europe and beyond.

Also important, however, is the connection these brands are forging between themselves and their customers. It’s a sense of community that reinforces both parties as key stakeholders in the transaction: the customers as loyal patrons, and the producers as reliable suppliers. Lukovkina pointed to one instance in which a local company recalled an entire shipment of their backpacks, refunded customers and officially apologized after it discovered a manufacturing defect. That may be standard operating procedure in the West, but it’s still largely new in Ukraine. “It was like Samsung or something,” she joked. “The future belongs to people like this.”

Better business practices are the only key to improving the local climate. Conquering red tape is also a formidable obstacle, especially in post-Soviet countries. In Ukraine, the state is attempting, at least in part, to streamline a clumsy and opaque bureaucracy through what Pavlenko says is seemingly ever-changing regulation. What’s more, for small producers like Pavlenko, who have grown primarily through social media, there are no clear rules on how to tax small-time businesses that aren’t the standard, brick-and-mortar type. But the more of these types of businesses there are, the greater impetus it could provide on the government to find coherent and consistent ways to deal with them. “We’re wrapped up in this process, and they’re wrapped up in this process,” Pavlenko says.

The industry here still has a long way to go before it achieves these goals. Among other setbacks, corruption and bureaucratic mismanagement still broadly hamper economic growth and remain incredibly difficult to surmount. Due to a lack of production capacity, for instance, many manufacturers here need to import fabric from places like Belarus to feed their production. But the Made in Ukraine movement is one of several sectors that could help lead the way toward healthy economic growth and greater transparency.

Dan Peleschuk is a Kyiv-based journalist who covers politics and society in Eastern Europe.