In tandem with his artistic partner Dima Erlikh, Roma Gromov has been well known in Odessa’s art scene for quite some time. Besides creating his own artworks, Gromov organizes the annual contemporary art festival Freierfest, and works as a curator at FADE IN and the Odessa Concept lab “Arteria.” He is now getting what could be construed as a big break with a chance to show his work at an exhibition running in the context of New York’s legendary Armory Show. “Trumpomania”, is a collection of representations by artists from 30 different countries, portraying their vision of Trump’s personality as well as what America’s presidential choice means for the rest of the world. The Odessa Review spoke to the artists about the seminal New York exhibition as well as mysterious plots, mirrors, and the state of contemporary art in Ukraine.

The Odessa Review (Olga Lumerovskaya): So the exhibition is opening in New York in the coming days. Are you flying out to be there for it?

Roma Gromov: Unfortunately, I am not. All this happened very spontaneously, without any extensive planning. I found out about the project three and a half weeks before the opening date, and I just barely managed to send the artwork in time.

OR: “Trumpomania” is not your first exhibition outside of Ukraine?

RG: No — there was Poland, an exhibition of Ukrainian artists in Chicago, Moscow, Italy… But this is the first high-profile exhibition. Going to Armory Arts Week in New York is a big deal.

OR: How did this happen? How did you get invited to the exhibition?

RG: The sam way that all interesting and extraordinary things happen in life — by being in the right place at the right time. We have long been acquainted with a curator from Moscow. I had shown her my works but that was about it. Everyone was doing their own projects at the time. She is part of a whole community of curators called 19.90. They are young women, curators from different cities — Moscow, Toronto, New York — and they do projects all over the world. Eventually, she became part of this “Trumpomania” project and they decided to encompass a large field geographically: Africa, Asia, America, Eastern Europe. One artist per country, 30 artists in total, presenting their version of Donald Trump’s psychological portrait and the way America’s choice of president will affect the future course of world history. So, after 3 years, this curator wrote to me that she remembered my works, followed my exhibitions and invited me to participate. There was no competition, because it was entirely the curator’s choice and project vision. She likes my statements, my irony (seen in the Roshen chocolate and Akhmetov sarcophagus installations which were part of Odessa’s Biennale in 2013 and 2015), sarcasm about political forces, that veiled irony with an Odessan touch and a conceptual twist.

OR: The work that’s going to the “Trumpomania” exhibition was created specifically for the project?

RG: Yes, that was the main condition for participation, that everyone create a work from scratch, using any technique but for a flat image. I think this is due to the high cost of transporting an installation, as well as paying for bringing 30 artists to the exhibition, that would require quite a large budget. The curators made a smart move — only flat images created specifically for the project and never seen anywhere before. They want to draw attention to the exhibition, that’s why it’s taking place in a parallel program to The Armory Show, the most prestigious art fair in the world. Getting there for an artist is like being catapulted into space. Any exhibition running during Armory Arts Week can become a parallel program and promote itself under that name. While The Armory Show doesn’t indicate these shows in their materials, it’s a good publicity opportunity for the parallel programs and a way to achieve the maximum concentration of great exhibitions within the widest possible geographic scope. This fair is incredibly popular: if an art work gets there, it will most likely be bought.

OR: Please explain the concept of your work, what did you want to portray?

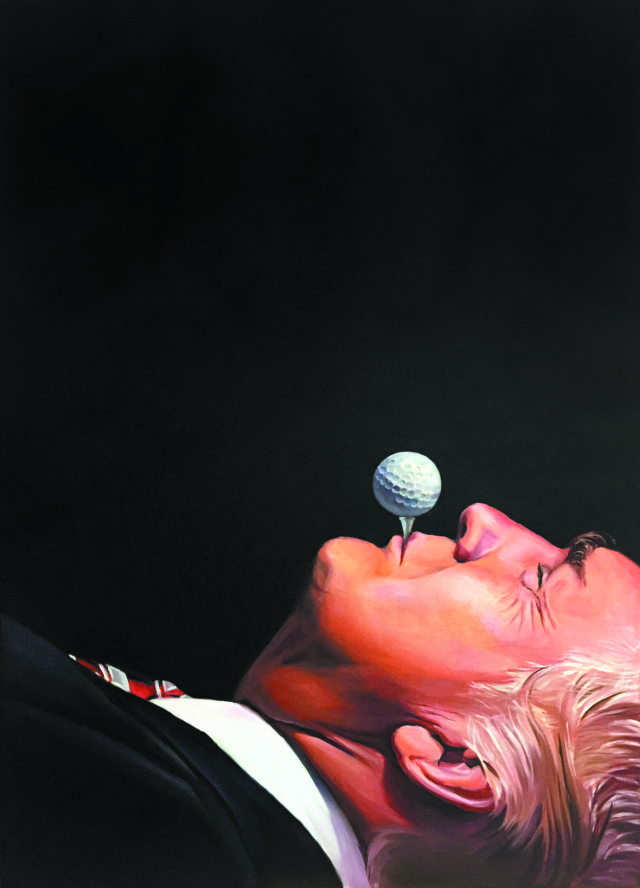

RG: Of course, we came up with the concept together with Dima Erlikh. We work in creative tandem almost inseparably, and also think through our solo projects together. In this work, we created a kind of mystery-adventure storyline distantly related to the plots of Guy Ritchie films. So: Trump loves golf! We started asking ourselves questions — what do we know about Trump? Who is he? Where does he come from and why did he go for the presidency? What does he want to do? We conducted a little poll in our circle to figure out what people think of him in Ukraine. We realized that the entire world does not know what to expect from him. We called the work “Who are you, Mr. Trump?”. The plot is that after a hard day, Trump goes to the golf course on his island in the Caribbean Sea. Suddenly, he is attacked by masked people, who pull him down on the lawn, put a golf ball on his face, swing back the club and, as in the movies, ask him a question. Only in films, the question is usually “Where is the money?”, but here he is instead asked “Who are you, Mr. Trump?”. Based on this story, we created a picture that looks like a frame from a movie, as realistic as possible, so as not to lose the cinematic feeling. We were asked if the work would be offensive, because the probability that the work will be seen by someone from his staff or even himself is quite high. But I saw some of the works and some of them are very harsh. Based on how we see him, with our signature irony, this is what we got. We did not want to fetishize or humiliate him. We wanted to ask a question that almost everyone has on their mind.

OR: When you were working on this piece, or others that had a political context — did you have a personal opinion, a political commentary that you wanted to make?

RG: Honestly, I hate the politics that we see in Ukraine — it’s dirt, trash, devastation, chaos and absurdity. Arrogantly, in front of the cameras, they pass drugs to each other right in Verkhovna Rada. It really looks like a movie, it’s unfathomable. It’s a circus and you put a mirror up to it. Contemporary artists and their works are like the portrait of Dorian Gray — the politicians know it exists and they know there’s a monster there and are afraid to look at it. But the time comes when they have to look. Our works are that mirror, it’s what they really are, but interpreted with the artist’s style and irony.

OR: Do you think it is the artist’s duty to reflect reality in this way?

RG: If we are talking about contemporary art, in the way the world understands this term, then of course we can’t remain apart from reality. Especially in Ukraine, where the issues are always coming directly to you — from TV, from the radio, from the people themselves. The artists are like sponges, absorbing all this. It’s a critique of reality: we reflect and aggressively focus attention on some parts. We are calling the audience to not be indifferent, to keep pace with modern culture. People have to understand that the art that we show them, just like the clothes they wear or the food that they eat, is the essence of modernity. You must be a man or woman of your time. Art and technology are always moving forward, everything changes completely. Art touches upon absolutely every area of human life — from the soul to domestic life. The most important thing is for the viewer to come and see the exhibition.

OR: Then, would you agree that the purpose of contemporary art is to make someone look at an issue from a different angle?

RG: Of course. We are a mirror, that is our main function. But there are different kinds of mirrors. The viewer gets into a room of distorted mirrors and sees everything differently. Preferably not even in a room, but a labyrinth, which really stimulates the imagination and thinking. Only in that context can you get what you see at the Pompidou Center – lines to see art! Only Relics of saints attract huge lines here in Ukraine, but in the rest of the world, if you bring an exhibition of René Magritte, you will get a line six months long! Contemporary art is like a cult, either you have the faith or you don’t. It’s a matter of openness, education and worldview. If you are educated, then it is easier for you to believe in and understand contemporary art.

OR: A hunger for such refined emotional experiences as contemporary art — is it environmentally conditioned or innate?

RG: It can be developed, of course, there’s also genetic memory: the French, for example, can’t be indifferent to art, because that’s where it was created. Same with Italy — geniuses were born there. Here, if you weren’t born with an openness to something new, you can only educate yourself. That is why it is more difficult for our audience to perceive art, because there is no reference to anything. The Ukrainian land didn’t have anything, not even the Renaissance. For this reason, there are huge holes in architecture, art, everything. On the territory of Ukraine there was nothing, even the era of rebirth was not. Because of this, there are huge failures in architecture, art. After all, everything that we have was brought here by the Italians, the French, and others.

OR: And so what do Americans have in their genetic memory?

RG: They bought everything. They are the main buyers of art: America is now home to the greatest quantity of art on the planet. They’ve got everything. What they didn’t have, they built for themselves, they even have an Odessa over there! American culture is a culture of business, a culture of relations. Maybe great minds weren’t born there, but they acquired everything they needed to become a great people.

OR: Is some level of prosperity necessary to free the mind for appreciation of art?

RG: Of course. If you are hungry, you will only think about food and draw food. Although, some of the most ingenious works of mankind were created during periods of crisis and stagnation. There is courage when there is nothing to lose, you can make a leap. Bold statements are brilliant statements. The myth that “an artist must be hungry” is complete nonsense. Comfort makes a big difference — galleries, grants, funds, museums, all these institutions must function in order to encourage development. In order for culture to flourish, it needs support. Russia is now arguing if Chagall is Russian or French? Well, who accepted him and fed him? The French. Russia nearly destroyed him. So where does Chagall belong? America in this sense is the greatest country. It welcomed everyone, so many people moved to America because of the financing or support available there — Diego Rivera, Marcel Duchamp, René Magritte.

OR: In this context, are you inspired to be an artist in Ukraine, or would you like to work elsewhere?

RG: I would like to work some place else, yes, though not so much as an artist, but a curator. For example, in Germany. The conditions for this kind of work are much better there, and it is more highly valued. The curator has a high status in society. I would like to gain experience there, but I want to remain a Ukrainian artist, because there is a lot to say here and it’s my land. I can never be a French or German artist, I’m from here. And you know, how in the Soviet Union, if an Odessa native was asked what his nationality was, he’d say he was an Odessite. Well, that’s what my nationality is: an Odessite and a Ukrainian.