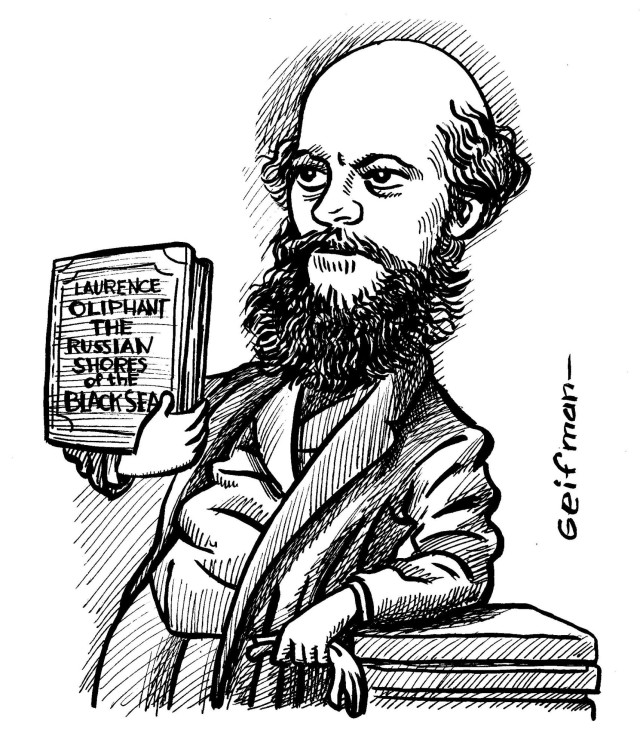

The 19th century British traveler discovers a cosmopolitan and colorful city whose inhabitants go out of their way to appear ‘as little Russian as possible’.

It was with mingled feelings of gratitude and triumph that I found myself climbing the steep hill which leads from the quay into the town of Odessa. I felt thankful that we had escaped three weeks’ quarantine; that we had passed through the customhouse without having our luggage examined; that there was a prospect at last of a return to some of the luxuries of civilized life after a somewhat arduous journey. And I felt triumphant, because I could now for the future fearlessly condemn Russian hotels, discuss the merits of Russian shops, and depreciate Muscovite civilization in general, without being told that I was not in a position to judge of any of these subjects from never having been at Odessa.

Hitherto my life had been rendered miserable by repeated allusions to the “Russian Florence”. Some infatuated Odessans on board the steamer impressed upon me for two days and nights that nothing I had seen at Moscow or St. Petersburg could give me even a faint conception of the glories of Odessa, which, according to them, combined in itself the charms of all the capitals in Europe. The statues and the opera were Italian; the boulevards and shops, French; the clubs conducted upon English principles; and the hotels unequalled in Europe – the whole forming attractions which may surpass my most sanguine anticipations.

It was evident that these benighted inhabitants of Odessa praised their city in utter ignorance of the merits of others

It struck me as somewhat singular, notwithstanding, to be told, upon asking what means existed of leaving this enchanting spot, that we should find it necessary to buy a carriage and post, as no diligence had as yet been established. Odessa, probably, is the only town in Europe containing upwards of a hundred thousand inhabitants, which cannot boast some public means of conveyance other than a post telegram, which is infinitely more barbarous than a Cape Bullock-wagon, and only meant for the conveyance of despatches.

It was evident that these benighted inhabitants of Odessa praised their city in utter ignorance of the merits of others. It could not seem strange to them that a pair of sheets should be charged a ruble extra in the best hotels, since they seldom or ever made use of them at home; while it was not to be wondered at that jugs and basins should seem superfluities to those who followed the mode of washing adopted on board the Russian steamer, which consisted in each man’s trickling a little water into his friend’s hands – so little, indeed, that but a very few drops of the precious liquid were spilt. Our exertions to obtain a basin on board evidently caused us to be looked upon as bad travellers, who did not conform to the manners of the country they were in.

The change from the climate, inhabitants, and customs of the East, to those of the bleak North, was very marked on our arrival at Odessa. We were again surrounded by sheepskins, and pierced with a sharp east wind that howled over the desolate steppe. Here were no lofty peaks to shelter us, nor summer sun to warm us; winter seemed fairly to have set in the day we arrived, with the view of chasing us out of Russia. However, we could not go until we had been advertised a certain number of days in the papers, for the benefit of imaginary creditors. Fortunately, we had given notice of our intended departure before we arrived, whereby the length of our stay was considerably diminished. Meantime we found plenty to amuse us in the greatest mercantile emporium in Russia.

It must be admitted that Odessa is very cosmopolitan in its character. Almost every country in Europe has its representative here, and the principal streets are filled with an immense variety of costume.

It must be admitted that Odessa is very cosmopolitan in its character. Almost every country in Europe has its representative here, and the principal streets are filled with an immense variety of costume. Indeed, Odessa has an air of business and activity about it quite foreign to Russian towns generally; and this is doubtless owing to its rapid growth and mixed population. There is a great deal more liberty enjoyed by the inhabitants than by those of any other town in the empire; and I was struck by the unwonted freedom of smoking and conversation which prevailed among those with whom I mixed. The evident effort made to be as little Russian as possible, is a significant comment upon the inconsistency of the inhabitants, who, while they maintain the superior excellence of everything national, seem chiefly desirous of sinking their nationality, and, with that facility of imitation peculiar to the Russian character, seek to assimilate themselves as much as possible to other European nations. It follows, therefore, that, apart from the novelty with which this city is invested by its commercial character, in a country affording no encouragement to trade, there is little to interest in its broad glaring streets, where clouds of white dust overwhelm the passengers, and rows of stumpy trees are reduced almost to the same colour as the tall houses behind them.

Odessa has existed to serve a definite purpose, and in that respect its case is altogether an exceptional one: it has been forced on in spite of government, by virtue of being a free port, and of possessing the most saleable commodity in Europe as its principal article of commerce. As its exports exceed the imports by two-thirds, its prosperity cannot be said to have a very firm foundation; indeed, a war with Russia would be fraught with more serious consequences to these provinces than to the country which derives its supply of corn from them. In the one case the ruin would be permanent and irretrievable; in the other, the contemporary inconvenience would doubtless be very great, but a new source of supply would surely be found, and one in all probability not liable to such sudden and violent interruptions. However, a consideration of the commercial interests of the Russian empire would never turn the scale with government one way or the other in a question of peace or war.