The American documentary film maker David Novack has been coming to Odessa for more than twenty years in connection with his interest in the work of the great Odessa born writer Issac Babel. This year saw the release of his long awaited film about the life of Babel. ‘Finding Babel’ represents a journey through his grandson’s quest in search of the writer’s legacy. The film has met with very good reviews and has been very successful during it’s Festival screenings. This interview took place the day before the film’s Odessa premiere (it’s second Ukrainian screening) as part of the 7th Odessa International Film Festival and the day after the The Odessa Review hosted a Babel conference along with Novack.

Odessa Review (OR): Hello and thank you Mr. Novack for speaking with us. We published a Babel portfolio in our inaugural issue so Babel is exceedingly important to the journal, our sensibility and to our view of Ukraine and Odessa. We are very excited about the film’s premiere.

David Novack (DN): Thank you very much, thank you for the attention that you’re bringing to this film while I am here. The Odessa Review is a blessing to the English speaking world who adores Odessa and its culture. I am very grateful to be talking to you at this lovely cafe in Odessa about Isaac Babel. What better place could there be?

OR: We know that you have a famous relative from Odessa and that you first came here to make a film about your composer ancestor, Mr. Nowakowsky.

DN: Yea that’s right. When I was about 28 years old, I learned that I had an ancestor named David Nowakowsky who was a composer of liturgical music at the Brody synagogue, here in Odessa. The Brody synagogue was a unique synagogue, it was the first to have an organ and an entirely musical service with a cantor and a choir of as many as 40 people. Many of those members of the choir were instrumentalists who played concerts at the synagogue and were part of the Odessa opera company. 1,300 of Nowakowsky’s manuscripts went underground in 1921, they were hidden from the Soviets and were later hidden from the Nazis in France, and they are now archived in the Yivo Institute in New York City. So I came here in 1993 to meet with scholars who would help me get me a better picture of David Nowakowsky, the Brody synagogue, and of Odessa before the revolution

OR: There’s more of it now, it has become an academic industry.

DN: Absolutely, absolutely, there’s much more now. One of my first stops was the Literary museum in Odessa where I met with Ana Missouk, who is one of the lead researchers, archivists, experts and tour guides at the museum. Ana turned me on to the Jewish writers who wrote about Odessa before the revolution. That was when I first read Issac Babel because, of course, he stood above all of them. In fact, the Brody synagogue and its music is mentioned in his “Odessa Stories”. It was a very musical place at the time. So I read Babel and fell in love with the “Odessa Stories” in 1993. I had trouble accessing the humor of the “Odessa Stories” when I was first reading them in English but it occurred to me that I already knew, from my trip in Odessa, about the Odessa language. I realized that if I read these short stories in English with my grandma’s Yiddish-infused accent in my head, I could access the humor. All of a sudden, I could see all of the sardonic sarcasm that is filtered throughout these stories in just about every other word – the double entendres, the hidden meaning, and the sarcasm. So, I fell in love with Babel at that point. Some years later when I was working on a film about Nowakowsky, I came across a gallery owner in the United States who had a collection of artwork by Yefim Ladyzhensky that had been used to illustrate Babel publications in the 1960’s Soviet Union.

OR: This was considered a great find, a particular historical artifact.

DN: Absolutely, in 2001 or 2002. I could not have found that in 1993, but the internet allowed to me to go in this direction during my Babel searches. I went to the exhibition, the gentleman let me film there and then he invited me to his home outside of Washington DC to do more shooting. He was very close friends with Antonina Pirozhkova, Babel’s second wife. Technically speaking, they were never actually married. As you know in Soviet times it was very common for households to be shared without a wedding. So this gentleman asked if I would like to interview her, and I said absolutely. I had read her published memoir, “By His Side,” and it documents the 7 years that she was with Isaac Babel before he was executed. It speaks of the work she did to find out if he was alive, which took many decades. She fought for his rehabilitation in the late 50’s. I read her memoir, went down to Washington, and I interviewed her. It was an extraordinary interview and I had no idea what I was going to do with that interview from 2002. It sat on a shelf in my office for years. Something told me that I just needed to get her story on tape. 7 years later, I read her obituary in the New York Times. I called to express my condolences to her grandson, Andrei, whom I had met when I conducted the interview. At that time, Andrei told me that he was thinking of going on a journey.

OR: He had waited until he was already an adult past the age of 40 to engage on such a journey. That is until he felt ready to take on this historical responsibility and this historical necessity. and only after his grandmother died.

DN: Absolutely, it seems that there was some kind of a torch that was being passed when his grandmother died. I said to Andrei at the time, “If you don’t mind me bringing cameras along, I’d like to go with you on this journey and see what comes of it.” So Andrei really conducted this journey, he arranged for all of the interviews, he arranged for everybody whom we met along the way.

OR: So he did it for himself, not for documentary purposes.

DN: Absolutely. Andrei’s original concept came from his acting. He’s a trained actor. He was raised in Moscow mainly by his grandmother and trained at the Moscow Conservatory. When we began the journey, he was already teaching acting at the Asolo Conservatory at Florida State University in Sarasota – a top notch drama conservatory in the United States. Andrei has a one man show he wrote about Babel made up of excerpts of Babel stories.

OR: And of course, Babel was a theater man. He adapted his own stories for the screen and he wrote plays.

DN: He wrote two plays. One called “Sunset” and one called “Maria”. Both are wonderful plays. “Sunset” is performed more frequently. “Maria” is a very complicated work which we explore in the film, Finding Babel.

OR: It has only been put on in Paris, as far as I know.

DN: There was a teleplay done in Paris as well by Bernard Sobel – he’s the last bastion of Jewish communist theater in the Northern suburbs of Paris. His theater is still there. We interviewed him for the film in that theater, but we didn’t use it in the film. So, Andrei had hoped that the journey would allow him to get close to Babel. He wanted to see how this journey might change or transform his performance as an actor. It was a little bit of an acting experiment for an actor to do that, to see what that kind of research, what that kind of digging, connectivity, putting himself in the spaces that are in the story, being in the lands of “Red Calvary,” or in the Moldovanka of Odessa, how could that experience actually transform his performance. Whenever Andrei felt like it, he would open up a story and start reading it, out loud, just start performing it.

OR: So he has a performative and a deeply embedded relationship to the work, he actually lives through the texts and cares about them. It informs his craftsmanship, his artistry.

DN: Very well put. That was the original concept, and I filmed him doing all these readings as we went along the journey. Ultimately, the decision was made not to include those in the film. The narrative of Babel that evolved was lost in them. We kept some excerpts, of course, but they are very edited for the film and we had them read by Liev Schreiber. The first cut of the film was three and a half hours and there are 300 hours of footage. Out of those three and a half hours, the next cut was about two hours and 15 or 20 minutes. At that point, everything that was in it was a gem and it was a matter of deciding which gems are we going to lose and why.

OR: When we spoke last night at our miniature academic conference at the literary museum, along with the local Babel experts, Russian literature experts, collectors, and the literature prized jury, you spoke about the extreme existential anguish of cutting these sections. The actual process of cutting anything from the film’s stock was very difficult for you.

DN: Yes, it was very difficult and I likened it to stories that we have heard and read of how Isaac Babel worked. Babel, in his study in Moscow, would walk around the apartment with a string that he would wrap around his finger continually and decide how he was going to edit down his works. His process was a process of editing as much as it was a process of writing. Editing painstakingly down to where every word and every piece of punctuation has weighted meaning. That’s what makes his work so rich and makes his work capture essences of people and moments. For a documentary filmmaker, it is very, very challenging process; If you’re going to make the best film you can make, you’re going to have to cast a very wide net. Frequently, casting that wide net means having much more amazing material than you could ever fit in a palatable film. Then you’re faced with commercial realities if you want your film to be in festivals – seen by many people. These realities require keeping lengths down.

OR: Did you ever think about putting together a crazed nine-hour epic with that material?

DN: I could have done that. At the time when I was making this, I was talking with the Kultura channel in Russia a lot, and we were talking about doing three 45 minute ‘hours’ which I thought would be the perfect miniseries. I would still be very happy to do that; I could restore this back to something that is a little longer length.

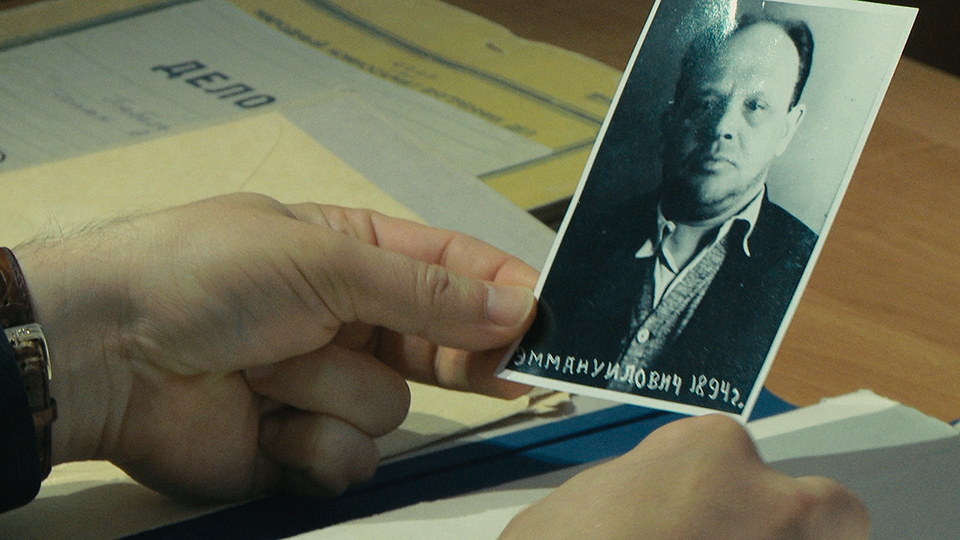

OR: Speaking about the situation in Russia, let us speak about the FSB archives in which you shot footage.

The head archivist at the FSB, Vasily Kristoferov, was very helpful, he made sure that we got permission to film in the KGB archives. We were the first American crew to be ever permitted to do that. We will also likely be the last for quite some time. He was helpful in allowing us access to what he knew existed or whatever he was permitted to let us know existed. He made himself available, he was very honest and open in interviews. But, still, he might have had some instructions from upstairs. There were a couple of pieces that were redacted, hidden or removed from the folder that we looked at. He told us that they were not there and he told us why. For instance, the document that shows the actual execution would have had the name of the executioner. His family has the right to privacy over that information becoming public.

OR: In Ukraine, as in Russia, this is a normative law. Although with the decommunization and the KGB archives, Ukrainians don’t have that problem as of May of 2015. This is well known fact that the families of the prosecutors, the lawyers, and the executioner are all allowed privacy. Also this is a matter of a fear of retribution.

DN: Which is understandable, but from the point of view of the victim and the victim’s family, they’d say, “Well I’d like to talk to the grandchild of that executioner and see what comes out of that conversation.” or “Why are my grandfather’s words, forced under torture, of public record but the name of his executioner isn’t?” But, as helpful as Kristoferov was, it seems that there is another large file that has gone missing.

OR: Did you have suspicions that he knows where the file is or he was not able to tell you about the whereabouts of that file. If he knew, it would shine light on the manuscripts.

DN: I don’t think Kristoferov does know where it is. What was missing… well there were two big things missing.. What we had, what Andrei was able to look at was the criminal case file that had all the details of the arrest, the case, the false confessions – which we know were given under torture. The recanting of his confessions, a letter where he says that everything he said is not true, is actually in the folder. Ultimately he signed his death warrant because prisoners had to sign that.

OR: All prisoners had to sign their own death warrant?

DN: Yes, and all of that was in there. What was missing was the day-to-day file which is a separate file which states specifically where he was sent and who interrogated him and what was said during that particular interrogation. And you know torture would be documented in there and all sorts of things would be documented in the day-to-day file. That file is missing. Clearly, such files don’t just go missing, especially for someone of his nature and level of cultural relevance.

OR: So we have our suspicions and we have nothing to base them on, is that the KGB or its successor agency, the FSB, still has these files under reasons unknown to us?

DN: I mean, yeah, either they have them or they were pulled up to the Presidential archive in the Kremlin. People have been in the presidential archive and there is a Babel folder which is not a prisoner folder. It has been studied.

OR: Do we know what is in it?

DN: Yes. There is a lot about Pirozhkova in it. I’d have to reread it. Jonathan Brent of Yivo who wrote a book about the Stalin archives has seen it, and there’s a significant section in that book about Babel.The other things that are missing are the manuscripts! 24 folders of manuscript of new writings that Babel had written throughout the 30’s and intentionally had not published.

OR: That is the collectivization stories?

DN: Yes, the collectivization stories and a few more Benya Krik stories, that we do not have. That is because Benya Krik never dies. In the film he dies. In the film directed by Vladimir Vilner (the 1926 version), he did not die in the original version. It opened in Kyiv, ran a few nights and it was then shut down by the authorities. Babel was made to rewrite the ending so that Benya Krik dies, where the proletariat rises up against him and kills him. But, in ‘real life,’ in Babel’s life, Benya never dies, he keeps going.

OR: Just like James Bond.

DN: Just like James Bond and just like the regime that Benya represented in the stories.

OR: What are the odds that the manuscripts exist? This is the holy grail of Soviet Lit after all?

DN: It’s always been Andrei’s dream. Once he understood what it meant, that a film was being made of his journey, it became a dream of his that the renewed exposure for Babel which is happening globally would help that process along. It is happening in Russia as well and the film can further fuel it. We hope that would result in the manuscripts surfacing, somewhere. What are the odds? I’m not a gambling man but I’d like to say 50/50 that the manuscripts really do exist. Why do we believe that? There is no record of them being destroyed. They certainly had been taken out of the KGB, or rather out of the NKVD, and they survived that time. There’s no question that they survived that time. The question is what has happened to them since, because certainly there’s a chance that they’re lost, that they’re in a box somewhere that’s never going to be recovered. There’s a chance that they were burnt in a fire, that there was a flood. Or, they could be on shelf, held by someone who understands their value.

OR: Let’s backtrack to the film and the reception in Odessa, to the conference that we organized on the 14th of July at the Literary Museum. You’ve been coming here for 24 years, and you’ve been dealing with the reception of Babel for a very long time. What is your take on the current state of ‘Babelonia‘ in Odessa, and of course Babel Studies in English speaking countries?

DN: It’s funny you should ask that. We were filming the magnificent monument of Babel created by Georgy Frangulyan, the famous Russian/Georgian sculptor, that now sits here in Odessa. We filmed him making the statue, to watch his hands, his work on that statue, creating it with a kind of love and understanding of that character of Odessa. He is from Georgia, he’s not Odessan, not an Odessite. The love for this writer across the entire former Soviet Union is the thing that has struck me most about going down this path and uncovering Babel. Then when you get to Odessa, it’s practically a cult.

OR: It is a cult in every sense.

DN: And as an American, to see a cult formed around literature is such a wonderful, refreshing thing. We don’t do that in the United States and we should do that in the US. I have to ask myself, what does Babel represent here, that it is a cult. There’s frequently scholarly meetings where they’re talking about Babel and many are talking about the cult of Babel in Odessa. They argue whether Babel is a product of Odessa, having come from here and experienced his childhood here, or whether Odessa is a product of Babel.

OR: This question is being discussed in a different register and linguistic apparatus at the literary museum which is full of Babel fanatics. The relationship is fanatical in both the absolutely enchanting and somewhat disconcerting sense. The obsession is creepy to the outsiders. It is a form of spiritual condition. They have built an identity for the city around the literature of Odessa. Separating Odessa from Ukraine, apart from the Russian speaking world equally. It’s a third place, an island onto itself.

DN: As was Babel. Babel represented the insider outsider, that’s what he was. He got himself all the way inside, up to the upper levels of the NKVD. Up to Beria who ended up supervising his torture in the end, personally. I don’t know if he was in the room, but he had an office in the St. Catharine’s Monastery where Babel was tortured. That monastery was being used as a torture prison, the Sukhanovo prison, which we note in the film, we visited it. He got himself as close to the flame as possible as an insider, but yet he was an outsider because he was from Odessa, he was Jewish. He should not even have been permitted to study under Gorky which is where he really honed his skills. The only reason that he was able to study under Gorky is that he smuggled himself illegally to St. Petersburg when he wasn’t allowed to be there, because it was outside the settlement area for Jews. So Babel was an outsider. He then found himself with Red Calvary with the Cossacks in the Red Army, running through Western Ukraine as he documented brutality against the Ukrainians and the Jews. Brutality brought on by both sides, it was a civil war essentially between the reds and the poles. Who suffered the most? The Jews and the Ukrainians, the peasantry are the ones who suffered the most in that conflict. There he was again, the outsider insider. It’s from this very unique perspective where all his writing came from. The great Yiddish scholar, Aaron Lansky, of the national Yiddish book center of the US – a repository of millions, at this point, of Yiddish books.

OR: He gave a great interview.

DN: Yes, I’ll be putting the full version online shortly. Aaron said “Babel is the quintessential Yiddish writer.” I said, ”What are you talking about ‘Yiddish writer?’ He wrote in Russian, he never wrote in Yiddish.” He went on to explain that’s not the point, the Yiddish writer is a writer from the outside looking in. It’s from a writer that no matter how much they feel assimilated; they still feel marginalized. That marginalization gives them a perspective and an allowance to write about something from a very different, unique kind of voice. That’s what Babel did better than any other. I think Odessa represents that same kind of idea.

OR: In what kind of way?

DN: Odessa’s a little bit on the outside, Odessa’s across the pale. It’s an international city, it has always been an international city. There’s a great account of the 1905 Odessa pogrom against the Jews written by a British nurse who was doing some kind of residency here in Odessa for a year or two when that pogrom happened. It was a very international city and as an international city it had a unique perspective on pre-revolutionary times, on the empire, and then on communist times. Even today, when you look at the conflict, Odessa is a unique place where for the most part, it’s very peaceful. It has had some problems, but there isn’t a war here. Hopefully, it will remain that way. But, there is a war of ideas here and that war can persist in Odessa because it’s a little on the outside of things in its own way.

OR: Even people here who are pro-Ukrainian, and that is a position that’s gaining ground here, and the vast majority of people here who are not pro- Russian, the city still has a local identity which supersedes anything else, by far. Loyalty to Kyiv is grudgingly given in some cases by the intelligentsia or the middle classes whose business prospects are dependent on peace. These people do not want to join a hypothetical separatist ‘Odessa People’s Republic’, understand that their lives would be much, much worse and there would be no business here if the port was under international sanctions. Still those people who say “we don’t want Russian tanks here,” believe that Odessa is Odessa, that is like Hong Kong, an island onto itself. So Babel is their civic religion. Babel is their cult of local history.

DN: Yes, I look at the play Maria in particular which was his last great work, which was published and ultimately shut down by the Soviets during dress rehearsals in Moscow. The play is about the revolution itself and is written from the perspective of 1935. That lasting message that I see when I look at all of this is that the revolution never brings the changes that one expects – that it creates an environment of chaos where some horrible things happen, and some great things happen. Down the road, what remains of the original ideals of that revolution can be very hard to find. Revolutions have a lot of unforeseen consequences. That idea is as important today in Ukraine and Russia as it is in the United States, Europe, and Syria. It is a constant struggle of humanity to bring about change, positive change, in a way that is sustainable and not simply reactionary. I think that Babel’s message is an overwhelming warning against tempestuous change.

OR: Let’s talk about the new slew of translations of Babel and what you think of the other attempts to bring Babel to the big screen. There have been other documentary films. It feels like a special film and you have captured things that no other person has captured. You have access that no other documentary filmmaker or director dealing with the material has had. You even have Liev Schreiber voicing the film! You have a wealth of material that even a less talented documentary filmmaker would make something decent with.

DN: The hardest part of making a documentary is the editing, because we have to create a narrative that doesn’t exist in a script. Let’s first look at what we captured. So in Andrei’s journey, he comes across myriad people who bring different perspectives to the story of Babel, to the work, but also to his life and what the last years of that life were like and why he made the choices that he made – particularly the choice to not stay in Paris and to return to Moscow.

OR: A fatal choice. But in the film, one that is presented as one that would’ve been fatal either way if he had stayed there as a foreign Jew.

DN: Gregory (Grisha) Friedin from Stanford university argues very eloquently in the film that he would’ve either been killed by Soviet agents in Paris or that he would’ve ended up in the gas chamber, one way or the other.

OR: Without a French passport, he certainly would’ve ended up in the Drancy internment camp.

DN: Yes, that’s right. What I discovered going through our footage was that Andrei was exposed to such a vast chorus of voices. The facts of Babel’s life became less and less important to the story-telling of the film. Instead, what Andrei discovered were essences of Babel, essences of the stories, essences of his life, essences of his arrest and execution, essences of the NKVD file. So much information is either missing or contradictory, that it became clear that Babel’s life was and still is an enigma. But the essences of what he was, what he did, and what he wrote about are palpable. Finding Babel became a film of finding essences. I know for the majority for our audiences, they are very satisfied with having that kind of visceral experience rather than a didactic one. I do know that some of our audiences do say, “But I want more about his life. I want more of the didactic documentary.” You know, there isn’t enough about his life in Odessa.

OR: That was in fact the main criticism at the Literary Museum conference from the local scholars. For them there two Babels. There’s “Red Calvary” Babel and “Our” Babel. Of course, they say that this is a tragic Babel that David chose to make for this film. That’s legitimate and that’s part of the story, but it’s not ‘our” Babel. It’s not the funny, ironic, quirky Babel from Odessa. They were slightly disaffected.

DN: That’s right. One cannot accommodate everything in an hour and a half film. Unfortunately, in terms of this sort of “funny Odessa” Babel, I came away from Odessa without really having that material, the material to truly support that for a number of reasons.

OR: Let’s talk about the reception in Moscow and the reception you’ve gotten from English speaking countries. Obviously, you won the jury prize at the Moscow Jewish Film Festival. Congratulations on that.

DN: Thank you very much. It was a great honor, particularly coming out of the Moscow Jewish community to receive that prize. And remember that for most of Babel’s writing life, he was in Moscow.

OR: That’s right. Looking back, most of the important stories were written elsewhere. Was the reception different in Russia from here in Ukraine?

DN: Not at all, I expected it to be different. I was a little nervous actually. Our first showing was in Kyiv at the Molodist Film festival in October, it was very well received and I was thrilled by that. Afterwards I showed the film in Estonia at the Black Nights Film Festival in Tallinn, where it was equally well-received. A few weeks later was the ArtDoc Film Fest in Moscow and I was a little nervous. One has to realize that I filmed these interviews and this journey in 2011 and 2013. The political environment, not only between Russia and Ukraine, but also between Russia and the US was very different when I filmed the interviews. People said things on camera that they perhaps would not now. I was concerned that it would be a problem for them and also my usage of those things was never intended to be political because it was done in a different time. While I was editing the film in the US in 2013, we were heading into a great escalation of racial conflict in the US which we are still in the midst of. This is in large part because of our lack of truthful, honest examining of our history of racial relations in the US. This is a problem that’s common to every major civilization that has been.

OR: To return to the particulars of the film, Ukrainians are actively looking at the past and it is being done in a very messy way. In some ways, the Ukrainians are dealing with the Soviet past in a totally radical and haphazard way. The archives are open, in fact it’s being done too quickly and in a politicized fashion some would say. Whereas Russia is going in the completely opposite direction and doubling down on the repression of its own historical understanding. The poison in the blood is being thickened as opposed to being drawn out. I’m quite curious, as you had made this film before that process had gone on as far as it had, what do you see in terms of the effect that the film might have had on local (that is Russian) conversations about the history of that moment?

DN: That’s a great question. So I went and I screened the film at ArtDoc Fest in 2015. At that point, I’m concerned about the conversation and what the ramifications might be. What I find is a sold-out, enthusiastic audience who is so thrilled and thirsty for this conversation that they see it as a validation of the conversations that I’m sure they’re all having at the dinner table. I think “Finding Babel” in Russia is part of a discourse that’s going on every day in Russia, but may be going on privately. Also, it is so exciting that there’s a new translation that will be coming out in the states soon by the great Val Vinokur.

OR: Yes. Our mutual friend Val is doing tremendous work. He wrote a remarkable essay on the history of translation of Babel into English for the first edition of the Odessa Review. It’s a fantastic piece and I’m honored to have had a chance to publish it.

DN: We used his new translations [in the film], he basically reorganized his work schedule to get to the stories that we needed. He would say “Well which ones do you need next?”, and I would tell him. We used his translations and we adapted them for the screen because some translations needed to be adapted for the screen, for the sake of timing and for the sake of legibility of subtitles. I’m very excited that these new translations are coming out. There’s a new translation in French that came out this year also I believe and there is a new translation in Mandarin that is being done right now. Babel is already in dozens of language and he continues to be translated which is a testament to how relevant he still is internationally.

OR: Finally, what is your favorite thing about Odessa?

DN: My favorite thing about Odessa is that there is a “Joie de Vivre” that I find pretty unique and which I find is also uniquely Odessan when compared with the rest of the former Soviet Union. Maybe because it’s a beach town, a vacation town, a party town, in many ways a very materialistic town, but also a fun town. When I was here in 1993, when Odessa was very impoverished, the only Western store was Benetton and nobody could get anything in it. Everybody was happy and partying then. And it was October, it wasn’t summertime. Live music was everywhere, this place had thriving nightclubs somehow. This impoverished place… It’s that Odessa spirit. I am so honored to have brought “Finding Babel” to Odessa, to have a chance to screen it outdoors for free on the steps for native Odessans. To watch them experience this piece of their cultural heritage particularly in a way that’s different, in a way that may have surprised them. To understand the Babel outside of the “Odessa Stories”, whom they probably might not know. It was my dream from the very beginning that this would have been one of the most important screenings of the film and it has turned out to be so. So I thank the city for having me, I thank the festival for having me. Also thanks to the Literary museum for hosting a conference and to the US Embassy for supporting my travel here. I thank the Odessa Review for conducting this interview and for giving so much attention to Babel since your very first issue. I think it’s important and it’s a great thing.

OR: Great, thank you for joining us. It has been a real pleasure to speak with you about Babel.