The Innocents Abroad; or, The New Pilgrim’s Progress is the title of the acerbically funny travelogue penned by Mark Twain during his 1867 trip through Europe and the Holy Land. In the course of his journey, Twain visited Odessa – sailing into the port aboard the Quaker City, a civil war era battleship converted into a passenger cruiser. The book was based on the extended newspaper dispatches that Twain wrote throughout the trip. It was one of his earliest literary attempts, and certainly his most successful book financially. It would also set the template for a new genre – that of the guileless American traveler making his way through the precarious and perplexing Old World. Twain exhibited the same irony and irreverence towards everyone he met and every locale he visited. The majority of his travels were spent complaining and mocking the local residents and customs. The bulk of The Innocents takes place before his arrival in the Holy Land; and for every place he makes a stop in, Twain makes it a point to compare the customs he encounters to the way things are done back home, rather unfavorably. Paradoxically enough, he reserves his most bitter criticism for his fellow American passengers, who exasperate him to no end. At the time of Twain’s visit, Odessa was young, vibrant and in the midst of construction. It was the same exact age as the United States, and in a similar position as an industrious, dynamic, cultural melting pot. It was these qualities which reminded Twain of America – and endeared the city of Odessa to him greatly.

The Duke’s statue, the boulevard, the Potemkin Stairs – all of these landmarks are still there, virtually unchanged from the time Mark Twain described them almost a hundred and fifty years ago.

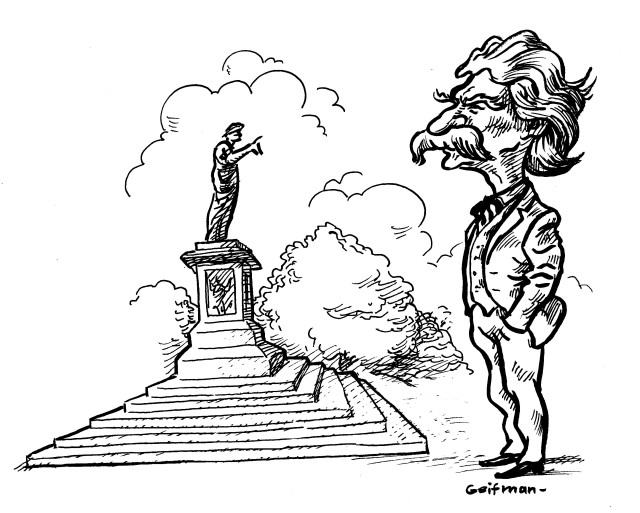

The Odessa passage of Twain’s book ends with his appraisal of the historical role of Odessa’s first governor, the Duke de Richelieu, as well as the statue of him which graces the Primorsky Boulevard and looks out to sea. The Duke’s statue, the boulevard, the Potemkin Stairs – all of these landmarks are still there, virtually unchanged from the time Mark Twain described them almost a hundred and fifty years ago. We have kept the nineteenth century orthography. It is fitting to republish the essay now, as The Odessa Review’s chief editor, Vladislav Davidzon is himself an American – with roots going back to Odessa.

“I have not felt so much at home for a long time as I did when I “raised the hill” and stood in Odessa for the first time. It looked just like an American city; fine, broad streets, and straight as well; low houses, (two or three stories,) wide, neat, and free from any quaintness of architectural ornamentation; locust trees bordering the sidewalks (they call them acacias); a stirring, business-look about the streets and the stores; fast walkers; a familiar new look about the houses and every thing; yea, and a driving and smothering cloud of dust that was so like a message from our own dear native land that we could hardly refrain from shedding a few grateful tears and execrations in the old time-honored American way. Look up the street or down the street, this way or that way, we saw only America! There was not one thing to remind us that we were in Russia. We walked for some little distance, reveling in this home vision, and then we came upon a church and a hack-driver, and presto! The illusion vanished! The church had a slender-spired dome that rounded inward at its base, and looked like a turnip turned upside down, and the hackman seemed to be dressed in a long petticoat without any hoops. These things were essentially foreign, and so were the carriages—but everybody knows about these things, and there is no occasion for my describing them.

We were only to stay here a day and a night and take in coal; we consulted the guide-books and were rejoiced to know that there were no sights in Odessa to see; and so we had one good, untrammeled holiday on our hands, with nothing to do but idle about the city and enjoy ourselves. We sauntered through the markets and criticized the fearful and wonderful costumes from the back country; examined the populace as far as eyes could do it; and closed the entertainment with an ice-cream debauch. We do not get ice-cream everywhere, and so, when we do, we are apt to dissipate to excess. We never cared anything about ice-cream at home, but we look upon it with a sort of idolatry now that it is so scarce in these red-hot climates of the East.

We only found two pieces of statuary, and this was another blessing. One was a bronze image of the Duc de Richelieu, grand-nephew of the splendid Cardinal. It stood in a spacious, handsome promenade, overlooking the sea, and from its base a vast flight of stone steps led down to the harbor—two hundred of them, fifty feet long, and a wide landing at the bottom of every twenty.

It is a noble staircase, and from a distance the people toiling up it looked like insects. I mention this statue and this stairway because they have their story. Richelieu founded Odessa—watched over it with paternal care—labored with a fertile brain and a wise understanding for its best interests—spent his fortune freely to the same end—endowed it with a sound prosperity, and one which will yet make it one of the great cities of the Old World—built this noble stairway with money from his own private purse—and—. Well, the people for whom he had done so much, let him walk down these same steps, one day, unattended, old, poor, without a second coat to his back; and when, years afterwards, he died in Sebastopol in poverty and neglect, they called a meeting, subscribed liberally, and immediately erected this tasteful monument to his memory, and named a great street after him. It reminds me of what Robert Burns’ mother said when they erected a stately monument to his memory: “Ah, Robbie, ye asked them for bread and they hae gi’en ye a stane.”