Translated from the Russian by Alexander Cigale

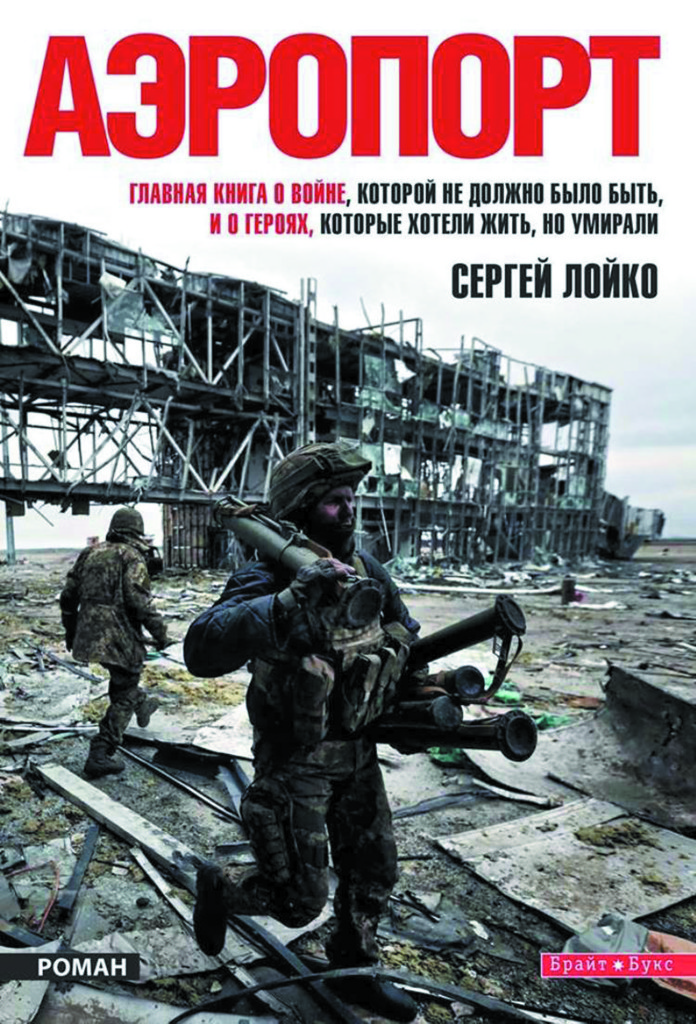

The battle for Donetsk Airport was one of the bloodiest and hardest fought in the now three-year conflict between Russia and Ukraine. The Ukrainian soldiers who defended the airport from attack by Russian–backed separatist forces came to be popularly known as “cyborgs” for their bravery and unrelenting stoicism. The airport’s control tower became a symbol of Ukrainian resistance. Surrounded inside the bombed out ruins of the once gleaming new airport, Ukrainian forces put up stiff resistance for months, before the air traffic control tower and other structures in which they huddled finally fell.

Sergei Loiko spent 23 years with the Los Angeles Times as a photojournalist, reporting from a number of active war zones. Born in Moscow in 1953, Loiko served in the Soviet army and later earned a degree in philology before becoming a translator and reporter for the Associated Press as well working in British television production. He has covered armed conflicts, revolutions, and wars in Romania, Tajikistan, Chechnya, Georgia, Afghanistan, and Iraq and created the well–known documentary book ‘Shock and Awe’ about the war in Iraq. Loiko was the only foreign correspondent to have been embedded (for four days) with the Ukrainian “Cyborgs” during the 2014 siege of Donetsk Airport, and later spent hundreds of hours conducting interviews with veterans of the battle.

The novel “Airport” is a fictionalized account of what Loiko witnessed in the midst of the fighting, and many of the novel’s characters and plot lines are based on specific individuals that he met and events that he experienced. The novel is considered by many to be the main cultural artifact to have come out of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

The novel was translated by the Russian-America translator Alexander Cigale, who won a 2015 NEA Literary Translation Fellowship. His “Russian Absurd: Daniil Kharms, Selected Writings” is just out from Northwestern University Press’s World Classics series.

Author’s Note:

Dear Reader! When in another twenty-thirty years or so, your grandchildren are grown up and able to read this book, I hope that the things it describes will be perceived as nothing more than a fantasy, Cyborgs vs. Orcs, or something of the kind.

“People did not want war. They wanted to live. And so they lived. The soldiers also wanted to live. But instead, they died.”

This is a book about a war that should never have happened. It is a book about heroes, who had no wish to die. No one wanted this war. But still, it happened.

This novel is neither reportage, nor an investigation, nor a chronicle. It is a creative fiction, based on facts. It is not only, and not so much, about war. It is also about love, treachery, desire, betrayal, hatred, fury, tenderness, valor, pain and death. About your present, past and, may God forbid, your future life.

Although based on real combatants, all of the book’s heroes are fictional characters. Any resemblance to persons living or dead is no more than a coincidence.

The majority of the military scenes and events are based on true facts and stories, some of which have been transposed in time and space, something that, however, does not make them any less real. Besides my observations of 2013–2015 during my trips to cover Ukraine’s Maidan revolution and the subsequent war, the plot of the book also contains stories and episodes based on hours of interviews with soldiers and officers of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

It is my hope that this book will be of interest to many, regardless of their age or character. It may prove appealing to some and not to others, but I would like to believe that it will leave only a very few feeling indifferent.

With my respect and gratitude to the reader!

CHAPTER I: YURKA THE TRAIN ENGINE

“And we ventured further— and I was seized with fear.”

Alexander Pushkin, “Imitation of Dante.”

January 15, 2015. Town of Krasnokamensk (Red Stone). Airport KAP.

On the landing strip, in dense fog, growling, having broken off their barking, ragged and gray, the shaggy mass of strays writhed, churning. Having gone feral over the period of the war, the starving dogs were now tearing away like wolves at the pieces of a still-living body (if one were to believe the image on the infrared scope from a distance of some seventy meters) of a separatist1.

The others had retreated an hour ago, carrying away their killed and their wounded. Failing in their attempt to rescue this one, they had left him behind.

At first, he was moaning while raising his good arm, as though in a gesture of drowning. Then, growing silent, he seemed to have lost consciousness. After a few seconds, like a ground blizzard or the Mongol cavalry, out of nowhere, the swarm of hounds descended on him, drawn by the aroma of blood.

Alexei lowered the infrared scope and suddenly sensed an unbearable pain deep beneath his left shoulder blade. His left sleeve began stretching taught and burst with a snapping sound. And then the other one, as though sliced with a switch blade.

On the cold concrete, gouged with bomb shell ruts, lying among the twisted wreckage of half-melted metal, was not the separatist but he himself. And the dogs were tearing away at him, tearing him to pieces.

***

“Alyosha! Alyoshenka! Rise and shine, my dear. We’ll be late….”

The embrace of Ksyusha’s warm familiar voice, tore him out of the fangs of the canines. He awoke. And now, still swallowing the chilly air of the underground, he was catching with his open mouth the drops of cold sweat running down his face in rivulets from under the helmet.

Ksyusha was nowhere to be found. She was not, any longer, even among the living.

With the occasional pangs of ruthless recognition of the irremediability of this, gradually, in waves of resurrected memory and in phase with the amplitude of the bare dim light bulb swinging to and fro under the poorly illuminated ceiling, with its stains and cracks, Alexei returned to the room — the only place in Krasnokamensky Airport (KAP) that was hardened against the large caliber machine gun bullets. Or more precisely, to what had remained of it by the middle of January 2015 of our Christian era.

Indeed, it was the most modern Airport in Ukraine, and one of the best in Europe. Built, by the way, only three years ago, for that very same Europe’s football championship. Now it reminded Alexei of the carcass of a leviathan gnawed down to a skeleton by the sea’s predators and spit out upon these shores by the merciless fate of an inexorable tempest.

The Airport’s complex of buildings had stretched out for scores of acres before the war – many of its structures and compounds, built during both the flowering and the collapse of the USSR and over the period of the subsequent decomposition of the now untrammeled Ukraine.

All of it, including the pearl of the Airport — the new terminal that is — was now in such ruin from the relentless firefights and bombardments that the SCC — the airport’s Security Command Center (as opposed to the Socialist Community Choir) — remained the only place with a floor, ceiling, and walls intact. It was inside the SCC that the recursion to the common-day reality of Alexei Molchanov – American photographer and former citizen of Russia – out of the fog of clinical amnesia first began.

The airport’s perimeter, for some few thousand meters, was so creatively disfigured by war that it at times seemed to Alexei that this was not even Stalingrad or Brest Fortress, but some Hollywood backlot set straight out of the latest blockbuster movie about World War II or the Apocalypse. He would not have been surprised had Spielberg himself materialized and, with the magic words: “Cut!”, the separatists and the cyborgs would, mingling together, amble off to remove their makeup and throw back a few rounds. But Spielberg did not make the expected appearance.

***

Surveying the ruins, it was impossible to conceive how all these chewed up by battle metallic ribs, along landing strips extending out from the central building, were still capable of standing. Same for the former building itself – bullets, shrapnel and shell rounds now for the most part simply penetrated through its ghostly hollows without meeting any resistance, if some of them were of course not to worm into the human flesh of those that had by now been defending something that was impossible to defend and which by any sane calculation was never worth defending for some two hundred and forty days.

Just as it was impossible to understand why those attacking it would wish to continue to spray the transparent ruins with lead and fire. And then send into the fray yet another wave of “volunteers,” the majority of whom would soon be returning to the country of their birth in numbered wooden boxes, jam packed into the refrigerated containers of a “humanitarian convoy”. To meet them, across the uncontrolled border, streamed new Russian “volunteers” and the regular troops of the Russian Army, together with thanks, armored vehicles, pieces of artillery, rocketry systems. Moscow was still denying everything, refusing to acknowledge the obvious….

By the tenth month of war, despite the short and shoddy periodic instances of cease fire, the Airport came to represent the vortex in the whirlwind of war, consuming, without thought or feeling, everything that both sides had flung at it — both the hardware and the men.

***

For their inhuman persistence and obstinacy, the enemies called the doomed men Cyborgs. They fought as though the fate of the war was being decided at this God-forsaken Airport. Moreover, not one of the cyborgs could have, eloquently or ineloquently, put into words why he would continue surviving here through each new day, as though it was his very last, why he was fighting with such ferocity. If we discard the readymade slogans, the explanation could be reduced to something like this: I am fighting because I am fighting….

The officers commanding the Orcs (that is what the Cyborgs called the enemy for his horde-like effacement and the impossibility of comprehending why he was even here or what he was seeking to accomplish) believed that the Airport must be taken at all costs in order to “even out the frontline” in the event of yet another “armistice”.

***

As the inevitable conclusion drew closer and closer, the men remaining in the Airport were a ragtag crew of foolhardy warriors — marines, paratroopers, rangers, sappers, some nationalists who had volunteered. Moscow was particularly insistent about the presence of the nationalists, declaring that the Airport, or the strategically important heights above Krasnokamensk, was controlled by a “fascist-Banderist punitive force, and the foreign mercenaries at their service, sent by the ‘Kiev junta’ to achieve the destruction of the brotherly hard-working people of the Donbass,” whom the Kremlin had for some reason elevated to the status of “our compatriots”.

The leader of this group was one of the last officers remaining alive. The Cyborgs obeyed his commands unquestioningly.

Were it not for the constant, even if not very effective, air support and the more or less regular resupply and rotation, one might think that the higher ups had entirely forgotten about them, that the Cyborgs and their Airport simply didn’t exist. That they themselves had the right to decide when to say “enough is enough!” and abandon the battlefield.

No matter how things were going, the order, when it came, consisted of exactly two words — “Hang on!” — and was fulfilled as though it were a commandment. The Ukrainian news outlets covered the Airport with reluctance, without any specific references, and no video or photos. At best, the screen would be commandeered by some tongue-tied personality – some or other high-ranking officer in a tailored uniform. Looking on with the dull eyes of a fish, he would, dispassionately mumbling, intone something about the figures or losses and announce some list of the place names of the military confrontations, occasionally including Krasnokamensk Airport among them.

By contrast, in the Russian news, the story of the events at the Airport would constantly occupy the lead. And so it indeed seemed as though some band of “ultra-fascists” were holed up at the Airport, who without cease, both day and night spray the town of Krasnokamensk from all types of heavy artillery.

In this version, the town should have long ago been erased from the face of the earth. In actuality, the firefights touched only a limited number of buildings peripherally adjacent to the Airport. In Krasnokamensk itself, more or less, daily life went on as before. The town’s hospitals, stores, schools, and even some factories all remained open for business. Public transport was running unmolested down its streets. Electricity, gas, and even heat flowed, just as before the war, with only occasional interruptions.

By January, the separatists had come to control the entire town, with the exception of the Airport, named after the great Russian composer and local birthright, Sergei Prokofiev. He would never have been likely to imagine, even in his most unrestrained flights of fantasy, the intensity of the fighting that would ensue between Russia and Ukraine for the Airport bearing his name….

***

Alexei began to gradually distinguish beyond the filthy table, some three meters away from him, a colorful group consisting of five Negroes…, oops, Afro-Ukrainians, wearing disparate military uniforms without insignia of distinction in various stages of unlaundered raggedness, and similarly variegated flak jackets and helmets. As if by force of some mysterious will, assembled here around this single table were warriors from various nations and epochs. Their common trait was the jet-black color of their faces, drawn-in looking and overgrown with bristles, fiery, sleepless eyes, but toothy white smiles.

The Afro-Ukrainians were laughing and cursing, somewhat reminiscent of miners who had just ascended out of the drift cut, with the headlamps on their helmets still burning. Despite the almost 10 months of war, no separate Ukrainian vocabulary of swear words had yet been invented nor, by the way, the operative Ukrainian combat jargon acquired. In the Ukrainian Army, including among those at the Airport, everyone with the exclusion of the commanding officer, who was from the Western part of the country, spoke in “the great and mighty” Russian tongue. In their short-wave radio communications, they also spoke Russian (if for no other reason than to be sure that the servicemen on both sides got the message). Truth be told, this Russian was somewhat non-standard, easily distinguishable by ear from clean Russian.

The Ukrainian soldiers controlled the first and the second stories. The third story and the basement were, for the most part, controlled by the Orcs. The basement, repeatedly mined and cleared by both sides, was joined to the underground infrastructure of the Airport by endless below-ground passageways. Rumor had it that some of these tunnels extended far beyond the Airport’s boundaries.

***

“Mike, Mike, do you copy? Damn it, do you copy, Mike!?” the commanding officer, Stepan, nom de guerre Bаnder (precisely so: Bаnder, not Bаndera, with an accent on the first syllable and without the “a” at the end), was trying to get through to the brigade’s headquarters for the hundredth time, but hearing in response only the crackling of the interference, he finally gave up and flung his walkie-talkie on the table. The lukewarm instant coffee splashed on his dirty hand.

“At Aeroport we do not wash! At Aeroport we scratch ourselves! Only those wash who are too lazy to scratch themselves!” The commanding officer yelled out in Ukrainian, having caught Alexei staring at him.

Everyone in the room had heard the joke so many times, they often repeated it themselves. And yet, they broke into a chorus of laughter all the same.

At the Airport, water carried the price of gold. The “limos” — the IFVs (infantry fighting vehicles), the APCs (armored personnel carriers) and MT-LBs (light armor transport vehicles) — making it through rarer and rarer, brought ammunition, reinforcements, personnel replacements once every two-three days, and carried away the wounded and the dead. And, of course, they dropped off produce, medications and water. But quite often the supply of water was so short that the fighters had to quench their thirst with the glucose and saline solutions also delivered, for lack of drinking water.

The use of the life-giving liquid for washing up and, even more so, for bathing, was considered a luxury bordering on the criminal. For that, there were wet wipes – a good thing too that the army was regularly supplied with these by the civilian activists and volunteers. It is precisely they who, in dedicated fashion, equipped the front lines with all the essentials — from toilet paper to military hardware and even firearms.

At times, it was impossible to make sense of how the staff logistics officers of the Defense and Interior departments satisfied the various supply needs of ATO, or the Anti-Terrorist Operation, a modest term used by the higher command to describe the hostilities bordering on an all-out war.

The fighters not so much laughed at the commander’s tired old joke as they were in a child-like way taking pleasure in the fact that they themselves were still alive. That yet another, the fourth of the day, attack had been repelled and the separatists, the Russian regulars, Russian mercenaries, and the Chechens of the Kremlin’s mixed-meat stew of a host had retreated. That the artillery, rocketry or mortar shelling, for who knows what time today, had subsided. And that it was now possible to sit around a table, warming your hands on the enamel mug of tea or coffee and, poking with your knife inside a tin of barley gruel, fish around for a piece of canned meat….

***

“Yurka, tell us again about the helmet,” one of the fighters requested.

Yurka, whose tag name was Train Engine, a young man, a railroad maintenance man before the war from neighboring Dnepropetrovsk, with relish and for God knows what time launched into his tale about how he was sitting in a deep artillery round crater, far off, almost by the separatist position, redirecting the firing, and how a shell-shocked separatist had stumbled into his foxhole….

After the partial expulsion of a string of unprintable interjections, Train Engine’s monologue continued roughly like this:

“So, this friggin’ separatist flops right down at my feet – damn! A machine gun, spanking brand new bullet-proof vest, but no helmet, wearing some sort of sports cap, like, pulled almost over his eyes, shit. I swing around and point my machine gun at him….”

Machine gunner Yurka, physically gifted no less than the brothers Klichko, did not part with his PKM 7.62 caliber machine gun even while doing reconnaissance or redirecting fire, as though he was afraid someone might steal it. Everyone made fun of him for this.

“And he, shit, does a double take, like he can’t believe his own damn eyes, that I’m a Uke. He thinks, like, I’m a, like, one of theirs, a fucking Orc, like, shit. They’re hunting a spotter, damn it, in the fog, that is, well, me, and I’m like, shit, right here with a machine gun. Like, what kind of an idiot goes out on recon lugging around a machine gun, like this, shit?”

His listeners are nodding knowingly in approval, draining their lukewarm (like little orphan Hasya’s piss) teas and the coffees of similar consistency, awaiting new details to arrive that grow more and more picturesque with each retelling.

“Before he comes to his senses, I, like, tell him right off: ‘You mother fucker, you’re unmasking me, you dipshit! Get the fuck outta here! Asshole! Can’t you see I’m hiding out here!’ And he, like, goes: ‘I got fucking lost myself. Fucking fog. The walkie-talkie’s on the fritz, I shit you not….’”

Around the table, everyone is laughing, anticipating the denouement by now familiar to all.

Once again, a chill descended on Alexei’s chest. His heart began again to hammer out the Morse code — arrhythmia. His supply of cordarone had been left behind in his backpack in the back of the APC that had driven off God knows where. He’ll have to dig through the platoon’s pharmacy bag in the SCC’s first aid station, the one with the Red Cross on the large pocket.

“I hand him my Motorolla — like, try mine, bitch!” Yurka accelerates his pace, intensifying the dramatism of his delivery, swinging his arms, fixing the helmet that had slid down his forehead, placing an emphasis on his consonants: “So he, l-l-like, s-s-stretches his hand out… B-b-bends down, b-b-basically, like this… I like g-g-get it, that I can’t damn well shoot him now, the fucking s-s-separatist foxhole is nearby, beyond the shot up APC. And I fucking take off my damn helmet and wh-wh-whack him with it right on the melon!”

Yurka takes his helmet off and almost foaming at the mouth goes on about how he beat that separatist with this helmet on his skull until it, “like,” cracked, “like a watermelon,” about how afterwards he sat over the body of the dead separatist for a long time with the bloody helmet in his hands.

“Damn it, it took me a while too to realize that I’m like all covered in blood, shit… I splattered the whole damn flak jacket, the vest, my entire face, even my pants… And the separatist, shit, there’s just one fucking solid mess, blood and bits of something, where his head had been….”

Total silence. No one is laughing. They all have their eyes down on the table or gazing at the floor. Today, Yurka’s tale had turned out particularly bloody.

He immediately understood this himself and transitioned to the subject of the man’s documents:

“So I, like, rifled through his pockets. A regular, damn it, I found his draft board card. The kid was from Orsk, damn it. Isn’t that in Siberia or something? A former artillery man. A reservist, damn it. Older than me by a year. And a photo of a gorgeous chick. All lady-like too, like, all done up and shit. Her hair styled, damn it… The commander’s got it along with the documents now.” Everyone’s anticipating that the latter will show the photo of the dead man’s girfriend to them at any moment, but Stepan turns away and once again tries to reach Mike.

What degree of savagery do people descend to in wartime — Alexei thought to himself. And later, it will turn out that the most vivid memory of Yurka’s life after all would be how he had bludgeoned a man to death with a helmet.

Alexei recalled his own “vivid” war impressions, and he began gasping for air. He walked out of the room into the pitch black of the cold terminal. The separatists at the other end of the landing strip began firing up a “snail” with its characteristic chomping sound — the grenade launcher AGS-17, so called for its round casing. “What for? It would just scare the infantry— thought Alexei, who knew something about small arms covering fire. — But all the infantry’s here. Drinking tea”.

Alexei retraced his steps back to the SCC, sunk into the corner onto someone’s bedding, got out one of his two cameras, and carefully removed the lens. He cleaned the camera and the lens from the inside with a miniature blower, clicked his favorite grimy, worn-out 16-35 mm wide-angle lens into place, and wiped it as best as he could with the little cloth from his eyeglass case. His other lens, with which he also never parted, night or day, was a 70-200 mm telephoto.

***

Fourth day at the Airport. A fourth day practically without sleep, without food and water. Communications almost non-existent; he managed to send the photos out only once, on the second day.

He remembered his earlier dream and the disembodied sound of Ksyusha’s voice in it. He remembered Nika’s voice. Entirely different. And yet both living, and desired. He reached for the phone. Looked over at Stepan-Bander. The commander was sitting with his back to him, by turns calling the battalion headquarters, then the brigade’s – equally futile. Alexei opened his messages and read Nika’s latest: “I beg you to come back. There’s nothing you can accomplish there”.

Chunks of plaster came raining down on his head. The room shook and rattled. Ear drums were nearly bursting from the explosions, as if the shells were going off in your head.

“Looks like they’re hailing down with Grads on us again!” Yurka-Train Engine yells out, flinging himself to the floor.

The others are already long recumbent. Their weapons are in their hands, cocked at the ready. Is it possible the separatists are going to try it one more time today?

Once the dust raised in the SCC by the nearby explosions settles and stops getting in everyone’s eyes, it becomes clear that this rehearsal is over. The fighters grab their tin boxes with the extra ammo, distribute among the pockets of their combat vests grenades of various types – the F-1s, RGDs, the frag grenades, for the launchers that attach to the rifle barrels of their automatics – and sling the “flies” and the other RPGs over their backs. They rush out beyond the massive steel door lacerated by shrapnel, taking their positions. Alexei, having forgotten about the pain in his chest, follows after them and, raising the camera to his eyes, on the run, adjusts the settings.

“Batman, report on the losses! Then, assume position!” Bander is screaming at the backs of the fleeing men and, having stopped Yurka with his hand, pulls him closer in, growls straight into his ear: “Keep an eye out for the American. He’s on your head!”

“Look after that fag?” Yurka repeats the question, grabbing with one hand his PKM and two tin cases of ammo with the other.

“You got that, right!?” Bander, rummaging with his hand though his combat vest extracts his cell phone. No signal. He checks his messages. No new ones. The last one, from his wife, yesterday: “I beg you, get him out of there. Love you. Yours, Nika.”