A profile of the young Odessa born film aficionado placed in charge of reforming the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Film Archives.

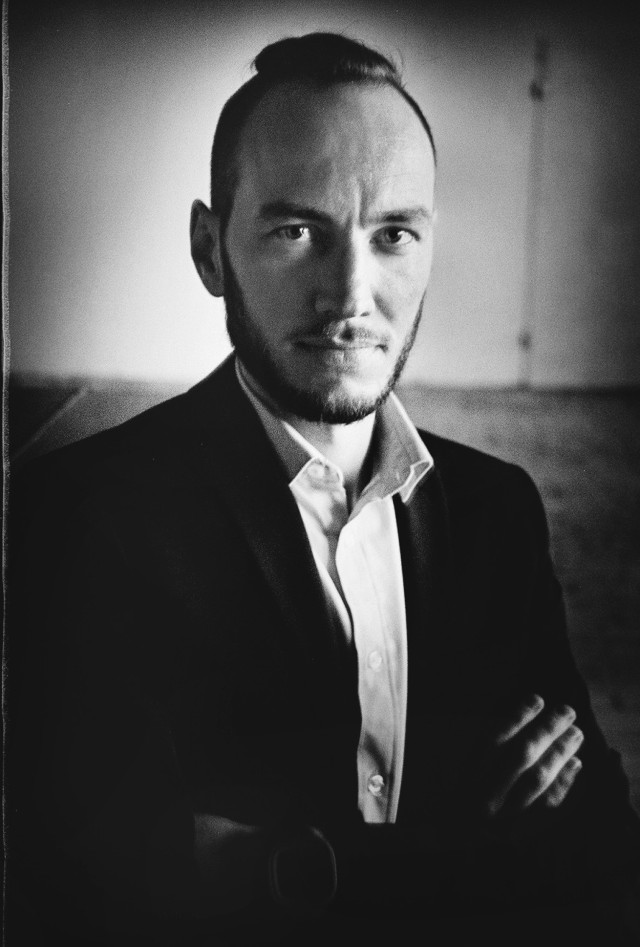

When I meet Ivan Kozlenko at the Oleksandr Dovzhenko Center he is wearing jeans and a light athletic jacket. As director of the center, Kozlenko, 35, has become a reformer in Ukraine’s state cultural sphere, a process that mirrors the more often covered economic reforms that have followed the Maidan protests in other parts of Ukraine’s sprawling state bureaucracy.

As we walk inside the building there is palpable energy as workers tear down walls. Dust is swirling everywhere as Kozlenko leads a group of older men in dark coats to his office, which is honeycombed deep inside the massive Soviet building.

What is now the Dovzhenko center was originally a factory for creating film for movie reels. In 1994 the industrial facility officially became Ukraine’s first film archive, and it inherited the negative prints of films from the Ukrainian studios that had produced them.

“We had to become a post-industrial institution,” says Kozlenko. “We couldn’t be about producing film stock anymore, but had to be about culture and meaning.”

Like many Ukrainian institutions, the center suffered from a lack of funds that has only worsened in the economic turmoil that followed the Maidan protests and the war in eastern Ukraine. When Kozlenko was first named director of the center in 2014, the need for financial creativity was only one of the many pressing demands of the post.

Ironically despite the need to break with center’s industrial past, it turned out that the Dovzhenko Center’s hulking Soviet industrial complex became its most valuable asset. Securing a special decree from the Ministry of Culture, Kozlenko won the right to rent out space and keep all of the revenue for the center. According to the ministry’s rules, normally only thirty percent of the revenue from renting space could be kept, with the rest returning to the Ministry of Culture.

That permission allowed Kozlenko to begin to revitalize and transform the center. He began renting out space to other cultural organizations, turning the building into a cultural center while also creating the revenue needed to fund other projects. Those projects have ranged from developing a new museum of Ukrainian film to creating new scores for Ukrainian silent films.

Kozlenko’s desire to bring music back to Ukraine’s silent films was what won him his first job at the center. In his native Odessa, Kozlenko was a silent film enthusiast and even organized a silent film festival. One day he met with the director of the institute and gave him a copy of the DVD he had made of Ukrainian silent films put to new scores. He was offered a job on the spot.

When Kozlenko started he was part of a new wave of young people that began working at the center alongside the old guard, many of whom had worked making film there for over three decades. As the the veteran staff continued cleaning and restoring the negative reels, the new generation began trying to raise awareness about Ukrainian film, getting around a cost-saving measures banning civil servants from traveling abroad by taking vacation days and raising funds to present Ukrainian films at international film festivals.

Part of the mission of the younger generation is trying to reclaim a legacy of Ukrainian film from the Soviet Union.

“We are trying to get people to not just identify with [Ukrainian] ethnographic culture, but with things that make people innovate,” says Kozlenko. According to him that approach resonates strongly with Ukraine’s youth, most of whom grew up in cities and not the idyllic villages usually used to depict Ukrainian culture. “When they see people from the 1920’s doing things like them then they connect.”

Kozlenko feels it is possible to talk about a Ukrainian film tradition even when Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union because the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic had film autonomy until 1930. In that period Kozlenko says that there was a liberal environment for making film that didn’t exist in the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Those films include the iconic “Man with a Movie Camera” by Dziga Vertov, and “Earth” by Oleksandr Dovzhenko, whom the center is named after.

Part of the center’s mission, however, is also to present Ukrainian film to the world and to reclaim films which are popularly known as “Russian” for Ukraine. In this Pursuit they have received support from people in the field like esteemed British film critic David Robinson, who encouraged Kozlenko to display the films abroad with their titles in Ukrainian transliteration, rather than Russian, to emphasize to viewer that the films were from Ukraine.

That mission has had its challenges. After the British film magazine Sight and Sound called “Man with a Movie Camera” a Ukrainian film, Kozlenko says it was attacked by Russian trolls. In the end they chose to refer to the film without a specific nationality.

Though Kozlenko’s work might be considered patriotic, his own background shows the complexities of modern Ukrainian identity. Kozlenko grew up in a Russian speaking family in Odessa and only made the decision to become a primarily Ukrainian speaker after the Orange Revolution. This means the idea of an inclusive contemporary Ukrainian identity with room for diversity, modernity and civic innovation is also one he is promoting for himself.

Not all of his projects have been without controversy. With a wave of anti-Soviet sentiment following the Maidan protests there was a risk that the films he championed could be rejected as “un-Ukrainian.” In April 2015 the Ukrainian parliament passed its first official de-communization laws, requiring Soviet place names to be changed and Soviet symbols to be removed from buildings and art. No one knew then how far the measures would go.

“We were faced with the prospect that these films could be banned,” he pointed out the irony. “These same films made in the twenties and banned in the thirties for being anti-communist could have been banned in modern Ukraine for being communist.”

So far that has not happened and Kozlenko and his team have continued with their work. Recently they also completed a catalogue of films depicting Ukraine’s Donbas region. Since 2014 the region has been engulfed in fighting, but in the Soviet Union it was a center of industrial projects.

They are working to acquire copies of all of those films, but many copies are only held in Russia and since the Maidan protests many Russian sellers are unwilling to sell to a Ukrainian state institution.

For now Kozlenko’s focus is on taking the center into the future. Digitizing the films, as well as showing and analyzing the films in their archives are all major priorities.

“Most people are surprised to hear that Dovzhenko was a Ukrainian filmmaker.” That is something that Kozlenko and his team are trying to change.

Ian Bateson is an American journalist living in Kyiv.