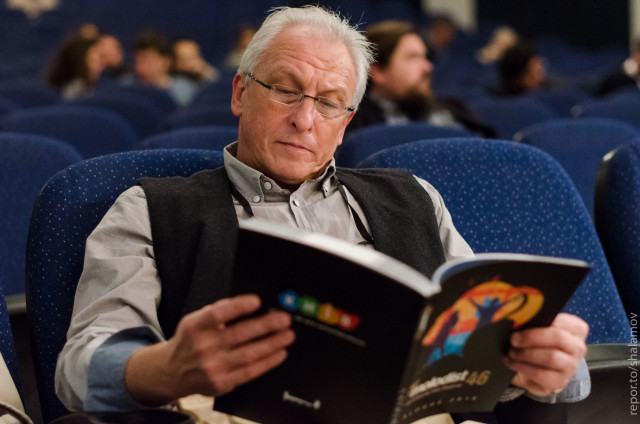

Listing every role that Alik Shpilyuk has played as an observer of the history of the Ukrainian cinema industry would be a near impossible task. He has worked as program director of numerous Ukrainian film festivals and is always to be found at Ukraine’s pavilion at any major European film festivals. Yet above all Shpilyuk is a passionate lover of film, a booster of Ukrainian cinema and a man who cares very deeply about making sure that Ukrainian audiences have a chance to see the best foreign film. This Autumn Shpilyuk was a member of the jury for Kyiv’s storied Molodist Film Festival. Shpilyuk met with The Odessa Review’s Managing Editor Regina Maryanovska-Davidzon during the hectic final days of the festival.

The Odessa Review (Regina Maryanovska-Davidzon): Mr. Shpilyuk, what were your impressions of the 46th Molodist Film Festival?

Alik Shpilyuk: Oh, so we will begin with a very global question?

OR: Yes, share your thoughts as jury member.

AS: Well, the impressions are that, finally, the entire time I was thinking to myself that I started torturing juries in 1991 and now, after 25 years, I got roped into being part of one myself (laughs). I also pity my foreign colleagues who don’t have time for anything except watching the competition program, without lunch or dinner…

OR: There have been complaints, that you were cruel when you were a programmer – making them watch 20 films in 6 days for example…

AS: I agree. It is inhumanly difficult work. I have it easier in the sense that I don’t need to walk around my home town, I know it already. The problem is that often, the thing to be most regretted is that you can’t watch what you’d like on the big screen. Of course, now you can always get links to everything, but some films you really do want to see on the big screen. But if you’re on the jury, then naturally you have responsibilities and you are not in command of your own time. On the other hand, it is always a pleasant experience, because you get a week filled with conversation about cinema, arts and culture with very decent people. I think this year we had a very nice jury in every respect, despite the fact… or maybe because we didn’t have any women on the jury, there were no emotional or distracting moments (laughs). And we remarked in our discussions that despite there being five people who represented completely different cultures, because one is a European, another a Canadian, nevertheless we always found common ground. We had disagreements and debates, but overall our views on cinema and on the program in particular were homogeneous, I’d say.

OR: What is it like to be on the jury after being part of the organizing committee for the festival for 10 years?

AS: What is it like being on the jury? In truth, it was odd, even after working on it for 10 years, but after working for 10 years and then not working for 15 years, and just attending as a visitor. Besides, last year and for a few years before that, I was on the FIPRESCI festival jury here at Molodist, you could consider that good practice. Although with the FIPRESCI, the work is lighter in volume and because it’s only full length features. After 15 years of attending the festival, though, you can understand all its complications, its drawbacks. If you get on the jury for the first time without knowing anything, some things can irritate you, stress you out, shock you even, but if you are internally prepared, you realize that it’s just that kind of festival… (laughs).

OR: In your opinion, what does the Molodist festival offer to beginning foreign filmmakers? For Ukrainian directors it’s obvious. Yet, for foreigners, how important is participation and the prize itself?

AS: It seems to me that there is a certain atmosphere of sincere interest because it is completely and totally directed at the cinema loving public. Both in relation to the competition and non-competition programs. So the competition gets the attention of people interested specifically in young cinema. I’m not sure if this festival gives more opportunities than others, but since it is specialized and designed for debuts and student films, it’s always beneficial for young filmmakers to be noticed, acknowledged, given some advice. So it offers as much as any other festival concentrating on young cinema. Moreover, the festival prides itself on following young filmmakers from their student works, to their the first short film debut, and afterward to their first full feature. If this really happens, that is a great stimulus for participants. I know that the traditional, if not slogan, then at least the mantra of the festival is that “Molodist introduced the world to currently well known filmmakers…” and then there’s a list of those who at one point had debuted their films in the Molodist competition programs, and subsequently became prominent, sometimes cult favorite directors who are closely followed. It’s nice, of course, if Molodist really discovered any of these artists for our viewers. I think the international audience came to know them not through the Molodist festival, but they could have been first noticed here. Again, I will say that for young debuting directors, any encouragement, any notice at an international festival is useful, pleasant and important.

OR: Did you only see the international program now?

AS: Yes, unfortunately I did not see the national program, but I must say that it repeated in many ways the Odessa festival’s national short film program. If there were any newer films, I have seen them in one way or another. For me, it was a good program. It featured the winners from the Odessa festival, a couple of fresh works. A good program, but I couldn’t watch it because the screenings ran during our jury discussions.

OR: Tell us about Ukrainian cinema today. What exactly do you think is going on today? Does Ukraine have a chance to produce a New Ukrainian Wave, like in Romania, for example?

AS: Not yet, because we have not gained the momentum. In the short format, there is development and a very interesting stream of films. Some of them have a length approaching medium form, which is a sign that in a little while they will start filming full length features. Then this wave should start to rise. For now, there are single features, here and there, like that of Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy, who has emerged as a serious star. What will happen with his next film “Luxembourg” — we shall see. That will also be a sign of the way film is developing. I know that right now Arkady Nepitalyuk is making a new film “Priputni” and it should be very interesting. There are indicators that suggest that Ukrainian feature film can gain if not critical mass, then at least a wide or medium scale of viewership. So that there are not rare individual cases, but some kind of statistical majority.

OR: What do you think hinders this from happening, and what promotes it?

AS: What helps, is the appearance of a sufficient amount of reasonable production companies, producers, who know what they’re doing, who have gained a lot of experience doing short films. It helps that the government does offer financial aid, even if it comes with problems and along with wasted effort. And of course it helps that, as I said, there are young filmmakers who have great potential. What hinders it? The fact that Ukrainian audiences don’t want to see Ukrainian films — because no matter how much potential these young directors have, no matter what they do, what kind of prizes they win at international and national festivals, if no one watches their films and they don’t get financial returns for them, I’m afraid all this development will cease. So it’s very important to teach the public to watch these movies.

OR: Should there be a quota for distributors?

AS: I don’t think that a quota would help. Maybe it could be the solution, but I don’t know. Otherwise, what stands in the way? Nothing else really (laughs).

OR: Does Ukrainian cinema have an audience?

AS: No, it doesn’t.

OR: Is this related to the lack of theaters in the country?

AS: Everything is related, of course.

OR: If we don’t just look at Kyiv, as the capital, but take Odessa for example. In a city with a population of one million there are not enough movie theaters.

AS: I totally agree. There is an excellent example with “Nikita Kozhemyaka,” which was very well promoted in Kyiv and Lviv where it took the major part of its box office of the first and second weekend. Distributors said that all other cities, including Odessa, came out to zero and everyone says this is because no one in those cities knew about the movie. It probably has to do with the number of movie theaters as well.

OR: So, what’s more important, the number of theaters or the education of the viewer?

AS: The education of the viewer is important also. Even in Romania, they don’t go to see Romanian films. It is almost the same story as in Ukraine. At least their films have appeared on the international festival scene.

OR: Maybe the fact the Romania is part of the European Union helps, they have more access to European foundations.

AS: Definitely. Another thing that threatens to really get in the way is that there are often unreasonable laws that are enacted by our lawmakers in relation to language regulations and such. On the one hand, there are good laws that allow us to increase the portion of government participation in film production, and on the other hand, there are populist things on the wave of “the most important thing we have now is our native tongue,” and that is a bit detrimental, I’m afraid.

OR: How would you describe young Ukrainian cinema, in a few words? Daring? Or depressing?

AS: In the best cases, the new Ukrainian cinema is daring, inventive, ironic, self-ironic, exploratory. Sadly, in our international competition there was one student film and one short Ukrainian film. There were no debuts, no worthy student films that hadn’t already screened at the Odessa film festival.

OR: What expectations do you have of films that are now in development, besides Slaboshpytskiy, whom you have already mentioned?

AS: It’s too bad I don’t have my list handy right now. I really like some new projects , as well as the projects that are already finished but can’t seem to realize itself at international festivals. I am always interested in the work of Alena Demyanenko and Dmitriy Tomashpolsky, because they have their own unique language and their own unique cinema. New projects that were now accepted to competition are also very intriguing. I am really looking forward to Arkadiy Nepitalyuk’s “Priputni,” also interested in “Shlyakh Mertsya” by Zhora Fomin which is now in production and will likely come out at the end of next year. There is the filmmaker Eva Neymann, who has only just started, and is currently writing her screenplay. And of course Sergei Loznitsa, I am always looking forward to his work. Maybe also the work of Kira Georgievna (Muratova)…

OR: Unfortunately for us, as viewers, Kira Georgievna is now on her well-deserved rest and is retired. Perhaps she got tired of the constant search for financing at her age.

AS: Age — that may be, but I just saw Andrzej Wajda’s final film, and it’s just fantastic.