A scholar of Stalinist architecture muses on its strange revivals in 21st century Russia and Ukraine.

During each of the past two summers, I spent a little over a month in Odessa, taking intensive Russian-language courses. I was attracted to the city by the maritime location, the high-quality language instruction – and crucially – by the relative absence of notable socialist-era architecture in the core part of the city center. As a writer on the afterlives and legacies of socialist state architecture, I figured that I could take a holiday from my work in Odessa. I would not be distracted by grand Stalinist ensembles or by particularly exotic specimens of late Soviet modernism, and thus could concentrate on my homework.

Indeed, on its surface, Odessa is a strange place to spend several weeks if you’re an enthusiast of 20th century state socialist, or modern architecture of any kind. Odessa – or at least the extensive, densely built-up central district, which constitutes the city core – is essentially a complete 19th century ensemble. It is a tight and well-preserved grid of Neo-classical and Art Nouveau buildings, pivoted around a monumental seaside set piece. That very theatrical ensemble centers on the famous Potemkin stairs (of Eisenstein tumbling pram fame), the monument to Duke Richelieu (the beloved first French Governor), and is flanked by several colonnaded administrative buildings, and the ornate opera house (a late 19th century addition to the ensemble). Odessa was bombed much less during the Second World War than other Soviet and East European cities, so there simply wasn’t the room, nor the desire, to create a grand socialist dream upon a Tabula Rasa.

If one looks more closely however, the picture becomes a little more complex. There are, in fact, a substantial number of Stalinist apartment blocks dotted around the city center, which were often built where bombs fell on older tenement houses. Most of these slot neatly, almost disconcertingly so, into the Tzarist-bourgeois cityscape. They bear little resemblance to the grandiose Socialist Realist edifices of Warsaw, Kyiv, Moscow or Berlin. With the exception of the over-the-top postwar train station, the bas-reliefs decorating their facades are more likely to feature horns of plenty or scenes of domestic bliss than muscular proletarians or glorious vanquishers of fascism.

There are a few 1930s Constructivist buildings here and there, which were for the most part built by architects from Kyiv and other Soviet cities. The most notable of these is the vast, monumental residential building meant for NKVD employees, which occupies the site of a demolished monastery in Odessa’s most prestigious district, adjacent to the city’s largest park. This summer, I was taken on a long walking tour of Odessa’s Constructivist heritage by the architectural historian Yuliya Frolova and by the archaeologist Cyrill Lipatov. “People are indifferent to the value of these buildings” Lipatov informed me. “They all love this eclectic 19th century stuff, which is everywhere, but they ignore the city’s modernist heritage. In Paris, London, Moscow or Warsaw – even in Kyiv! – people appreciate the modern movement. But in Odessa they simply ignore it”.

Beyond the historical core, of course, the majority of the city is composed of enormous, planned housing estates (micro-districts, as they were called by Soviet planners; or dormitory districts, as they are known by the city-dwellers themselves). I went for a walk around Cheremushki, the oldest of the micro-districts, built during the 1950s and 1960s. The streets are wide and lined with trees, the gardens and common areas are well-tended to. My guide, the architect-artist Alexey Belkorenko, showed me how Cheremushki looks on Google Maps – it’s abundantly green compared to the remainder of the city. There is a large, well-kept park, still called Gorky Park, after the renowned 1930s Socialist Realist writer who spent time in the city. The central building in the park is a large modernist cinema, still called the Kino Moskva. Cheremushki and other places like it are where most Odessans actually live.

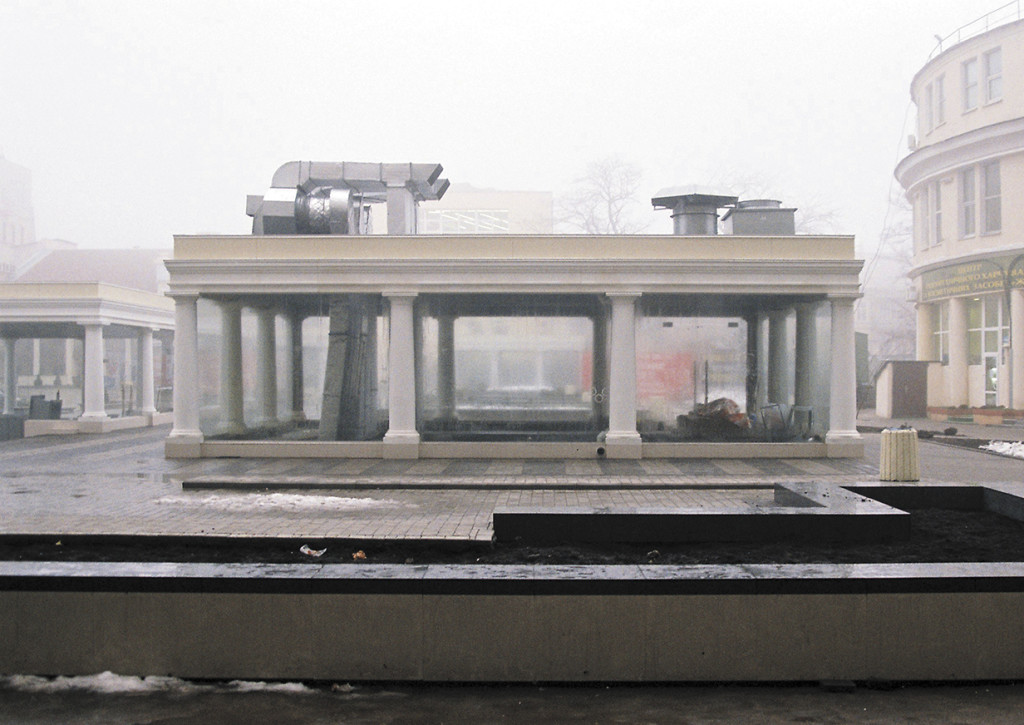

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, and the abandonment of the strict (if not always humane) planning regime which characterized the era, the development of the city fabric has taken on a distinctly hodgepodge, profit-driven character. In effect, a number of rather monstrous eyesore structures have been perched in the very center of the city (not to mention outlying districts, such as the resort suburb of Arcadia, which has been almost completely disfigured during the past quarter century). Completed in 2003, the Afina (Athens) Shopping Mall is a sprawling oval pile of limestone, stucco, glass and steel. It looms high over the city’s Greek Square and the main tourist thoroughfare, Deribasovskaya Street. Afina mimics the style and shape of the old Round House (or Mayorov House), which had stood on this site since the 1840s. It was demolished during the 1990s to make way for the ‘Capitalist Realist’ retail castle that stands there today. The Afina is surrounded by an awkwardly landscaped obstacle course of fountains, mini-staircases, faux-antique bollards and quasi-Grecian monumental sculpture. In the center of this obstacle course is a bust of an ethnically Greek 19th Century Odessa Mayor, Grigory Marazli (Grigoros Marazlis), remembered in Odessa as a legendary reformer and modernizer. The Greek-born developer behind Afina, who unveiled the bust together with the city Mayor in 2016, makes no secret of his wish to be identified as a modern day Marazli. It’s worth noting that the new bust was, in fact, the second monument to Marazli unveiled outside Afina. A larger one, dating back to 2004, was unceremoniously relocated in 2008 to make way for the entrance to an underground car park (leaving the elaborate colonnade which had flanked it flanking nothing).

The quaint completeness of the city’s 19th century appearance is also neatly disrupted, by the enormous cargo port – the Black Sea’s busiest – which hugs the coastline of the city center. Many visitors are additionally shocked by the sprawling, 1960s passenger terminal, which sits carbuncle-like at the foot of the Potemkin stairs. They are often even more amazed by the high-rise, glass-fronted Odessa Hotel, a wart on top of a wart, built atop the concourse of the terminal during the 2000s by an overzealous developer. The hotel is already derelict.

Non-Stalinist Neo-Stalinism: Capitalist Realism, Odessa Style

The Odessa Hotel – built in a provincial Neo-1990s postmodern style – is, in fact, rather unusual in Odessa, as it is one of the few recent buildings completed in the city in what is a vaguely “contemporary” aesthetic. Nevertheless, for all its shininess and symmetry, it is broadly consistent with the reigning style of architecture in Odessa during the last twenty years. Practically all recent housing and commercial developments in the city are finished off in a luxury Neo-Stalinist idiom, for which critics Bart Goldhoorn and Phillip Meuser have coined the phrase “Capitalist Realism”. That coinage naturally echoes and builds upon the grandiose official aesthetic of the Stalinist epoch – Socialist Realism.

The “commonsensical” understanding of this sort of architecture is that, on one level, contemporary Neo-Stalinism is a legacy of the taste for grandeur and enormity consolidated in the former USSR during the Stalin years (and extending further back to the Tzarist period as well). Part of the blame for the grandiosity of post-Soviet Neo-Stalinism is often laid at the door of the aesthetically monotonous character of the architecture of the immediately preceding epoch: the late Soviet 1960s-1980s. The narrative is that, as soon as the Soviet Union disintegrated – and with it many planning regulations and restrictions on private initiative – a process of aesthetic “overcompensation” began. Private property was introduced more or less out of the blue and the psychological desire to overcompensate merged seamlessly with the capitalist imperative to accumulate without restraint and to consume with conspicuity.

However, Goldhoorn and Meuser’s analysis points out that the singularity of post-Soviet Capitalist Realism does not lie purely in the sudden embrace of an unfettered market. This style, in fact, was developed in a top-down manner during the 1990s in Moscow, as the big Soviet state-run construction enterprises morphed into privately-owned property development consortiums. However, these mega-firms retained their centralized administrative apparatuses and their connections to big-gun political decision makers in the municipal administration. In Moscow the developer-municipality complex was utterly dominated by the towering, charismatic figure of Yuri Luzhkov, the powerful city Mayor between 1992 and 2010 and husband to the capital’s largest property developer, billionaire Elena Baturina. Luzhkov made it a personal mission to impose his taste on the city he reigned over, attending planning meetings and censoring construction projects which did not adhere to his “aesthetic principles”. In the summary of architectural historian Alexander Rappaport, these principles are: “in the center we only build historically, glass only in the suburbs, no smooth facades”.

To be sure, the origins of Capitalist Realism are multi-faceted, connected also to global trends in international Post-modernism during this period (the family resemblances to “Trumpitecture”, the style characterizing the new American President’s real estate investments are difficult to ignore). They cannot however be reduced to the aesthetic preferences of one person. Still, within the former Soviet sphere, this Neo-Stalinist style fanned out from Moscow to other cities, and arrived eventually in Odessa. As I walked around Odessa with Yulia Frolova and Cyrill Lipatov, Yulia told me stories about ready designs being bought wholesale by Odessa developers from Moscow-based companies, and reproduced in their new location as minimally-adjusted facsimiles. Thus, the monumental, 20-something story, multiple tower “Capitalist Realist” complex Tchudo Gorod (Miracle of the City) is an almost exact copy of a similar project in Moscow. More frequently, when no such direct borrowing occurs, the designers of Odessa complexes cite freely from facades or planning compositions which had already been tried and tested in Moscow.

There are plenty of Capitalist Realist buildings in other cities throughout the former communist world, of course. But the difference between Odessa and other post-Socialist, as well as Ukrainian cities (such as Lviv, Kharkiv or even Donetsk) not to speak of Moscow, is twofold: firstly that there is almost only neo-Stalinist architecture being built in Odessa now; and secondly, confusingly enough, is that there is relatively little Stalinist architecture present in the city itself. Yet it is here, in Odessa, that the “aesthetic principles” enshrined by former Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov in 1990’s Moscow exert a particularly unchallenged impact on a pre-existing urban fabric. It is thus that Non-Stalinist Odessa is busy turning itself into one of the world’s purest examples of a Neo-Stalinist urban landscape.

The Satirist Architects of Peresyp

Although there is not much of an architectural alternative to Capitalist Realism on offer in contemporary Odessa, the city’s hegemonic style does have its homegrown ethnographers, artistic (re)interpreters and satirists. The members of MNPL (or Monopoly) Collective, a tight-knit group of young architects, designers and (most of them Odessa natives), scour the city for aesthetic and anti-aesthetic inspiration. They photograph the bizarre grandiosity of the Capitalist Realist mega-developments. But they also pay attention to a different kind of slapdash vernacular aesthetic. It is an aesthetic that populates pavements, courtyards and facades in every nook and cranny of Odessa. The architects regularly upload their findings onto social network platforms such as Instagram, Tumblr and Facebook.

Flowerpots made out of tree trunks or toilet bowls; tree stumps painted over with the colors of the Ukrainian flag or decorated with multi- colored buttons; dead tree trunks painted white and functioning as portals to luxury health spa complexes; Flinstonesque park benches fashioned out of clay; Art Nouveau plasterwork re-deployed as wiring supports; medieval turrets hanging precariously from bungalow roofs or stuck onto the sides of factories; drainpipes elaborately sculpted to mimic the shape of plasterwork on building facades; fake grass planted around tree trunks or inserted into gaps between bricks; gold-colored iron sheets stuck, in the style of Frank Gehry, onto the fronts of haphazard little sheds; Neo-Constructivist or pseudo-Deconstructivist sculptural formations attached to otherwise unassuming roofs and facades; disembodied Babylonian arches standing in front of dilapidated warehouses.

Several themes recur in the photographs uploaded by the workshop members. There are the elaborate things made out of old tires: polychromatic Towers of Babel, entire children’s playgrounds or paddling pools for plastic pelicans. And, perhaps most significantly, there are the counter-canonical experiments with the classical orders: kiosks shaped like Greek temples; bas-relief smiley faces sculpted onto distorted column capitals; monumental formations arranged out of air conditioners above doorways on historical buildings; ionic columns painted onto unglamorous rough concrete garden fences.

This enormous project of documentation doesn’t take place purely for its own sake, however. Almost every day, the members of the MNPL crew meet in their workshop, located in a disused factory complex in Odessa’s Peresyp district, a tangled dystopia of pipes, wires and dereliction backing onto the peripheral sections of the city port. There, they work the scattergun anti-architecture that they have collected from deep with Odessa’s interstices into grand visions. Visions which are drawn and rendered with the help of sophisticated 3D modeling software.

The group consciously work in the tradition of late Soviet “paper architects”, such as Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin, who spent the late 1970s and 1980s etching, drawing and painting bizarre architectural hells and paradises, unable (or unwilling) to secure any large-scale commissions. Whereas the original paper architects were loath to engage with centrally-planned, patronage-tarnished, mediocrity-laden late Soviet architectural realities, the MNPL workshop rebels against the profit-fetishizing, aesthetically-bankrupt expectations of clients in 21st century Odessa. “We don’t want to build the sort of shit people want”, explains Alexey Belkorenko, one of the collective’s members. Instead, these young anti-architects – trained architects Belkorenko and Viktor Prokhorov, graphic designer Lesha Mikhailov and 3D animator Ilya Soldatov (as well as people who participate in individual projects) – take on a few small-scale commercial commissions here and there, to fund the equipment and time needed to forge their 3D-rendered utopias.

The MNPL crew is occasionally commissioned by large new commercial enterprises or shopping malls in Odessa to design benches for the corridors or artwork for the façade. This is where they begin to experiment with the limits of the city’s aesthetic sensibilities. One recurring theme in their work is the sort of slapdash quasi-classical Ionic or Doric column, typically encountered propping up a private house, shopfront or condo complex somewhere in the city. This sort of column crops up in many of their paper architectural visions and thought-experiments. When they were commissioned to design a decorative billboard for the façade of a new box-shaped suburban shopping center, the MNPL workshop wheeled out this sort of column once more. Their design saw the very same column reproduced numerous times against a plush purple background, and plastered it onto the shopping center’s grey steel façade. The client, says Alexey, was not in on the joke. “They had no idea we were taking the piss. We’re not even sure if we were taking the piss. In any case, they really liked the columns, they thought they were really nice and made their shopping center look impressive”.

MNPL workshop, in other words, work firmly within the stiob tradition of late satire, which blurs the boundary between fiction and reality, humor and seriousness. Their work pays testimony to some extent, also, to the continuity between the vernacular aesthetic of post-Socialist Odessa, and the top-down luxury kitsch of developer-sponsored Capitalist Realism. It is not purely the developers imposing their multi-story Neo-Stalinist castles on Odessa: many Odessans want to live and shop in these castles, too; or at least to plaster, paint or transplant some aspects of their visual language onto their own homes, streets and workplaces.

It would also be misleading to suggest that these buildings are all simply parachuted into Odessa from Moscow, without any consideration whatsoever for the local context. In Belkorenko’s terms, many of the grandiose structures built during this epoch are examples of what he calls a “provincial contextualist” style. He singles out three buildings in Odessa as paradigmatic examples of such a “provincial contexutalism”: the enormous Chornomorets football stadium in the center of Shevchenko Park, the city’s new airport terminal and the aforementioned Afina Shopping Centre. In each of these three structures, he says, you have this “naïve desire to fit into the context of the city. The airport roof imitates the wavy sea (geographic contextualism); the stadium directly takes elements of décor from the neighboring City Hall building; In Afina, a desperate attempt is also made to blend into the urban ensemble of Greek Square… In effect, you get this spontaneous sensual collage, which very successfully pays testimony to its time and place”. Echoing an argument from architect and critic Dasha Paramonova’s book on Luzhkov-era architecture in Moscow, Belkorenko even argues for the necessity of conserving selected exemplars of this type of architecture, if they were ever threatened by demolition.

Architecture critics tend to dismiss these kinds of buildings as “kitsch”. Of course, say the critics, this kitsch architecture exists in the West too, but only at the “fringes”: on the margins of the profession, in suburbs of cities or in small provincial towns. The sophisticated architects of the Euro-American architectural elite – allege the critics – only mess around with Graeco-Roman, Byzantine or Sumerian associations if they’re being “playful” or “ironic” – as can be seen with the case of the towering figures of 1970s and 1980s American post-Modernism, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown, whom Belkorenko himself frequently invokes as a partial inspiration for the work of MNPL Collective.

This narrative about “kitsch” only being located at peripheries is, of course, highly questionable. A ten-minute walk around London, Washington D.C. or New York – where arrière-garde multi-story monstrosities ride roughshod over city fabrics with impunity – is enough to dispel such an idea. Yet the architecture of first world cities – or at least America’s – may be about to take on a more dramatically “Capitalist Realist” character than they have ever before. The United States President-elect Donald Trump is well-known for his many failed real estate ventures throughout the former socialist world, from Moscow to Kyiv, Baku to Batumi, Warsaw to Yalta. He is also known for his close ties to some of the highest priests of Capitalist Realist aesthetics. Among these are Luzhkov’s court sculptor, Georgian-born Enfant terrible Zurab Tsereteli, whom Trump attempted to recruit to design numerous outsized sculptures in New York – including a gargantuan monument to Christopher Columbus to have been built on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. That monument would have surpassed the dimensions of the Statue of Liberty itself.

Architectural aesthetics are always dependent on politics and economics. Everywhere in the capitalist world, realtor capital is intimately connected to political power and decision making power. But, in most places – especially in the Euro-American heartland – shady links between developers and decision makers have tended to be fairly well camouflaged or disavowed. Even in Luzhkov’s Moscow, the Mayor was not actually a developer himself – he was “only” married to one. In Trump’s America, however, the realtor Trump no longer has an influence on politics – he is politics. He embodies the sum total of the political. Donald Trump is the world’s first property developer president.

Perhaps, then, if we are truly looking for a sneak preview of what shapes and styles will come to populate the Trumpitectural landscape of the New Great America, we should look to the cities of the former socialist world for clues; and, in particular, we should be looking to Odessa. It is in the southern Palmyra where Capitalist Realist politics and aesthetics have taken root to an extent scarcely encountered elsewhere. And, perhaps, if America’s new breed of dissident architects want to start honing their skills of resistance and subversion – and their senses of humor – they ought to start taking lessons from the architectural satirists of Peresyp.

Michał Murawski is an anthropologist of architecture, currently based at Queen Mary, University of London, where he is a Leverhulme Trust Fellow. His work focuses on Warsaw and Moscow and examines the legacies of communist-era architectural fabrics in 21st century East European cities. His book, Palace Complex: The Social Life of a Stalinist Skyscraper in Capitalist Warsaw, will be published by Indiana University Press in 2017.