As a documentary, “Myth” could have easily descended into hero worship. It had all the prerequisites: a talented and extravagant protagonist, a patriotic theme, and a receptive audience.

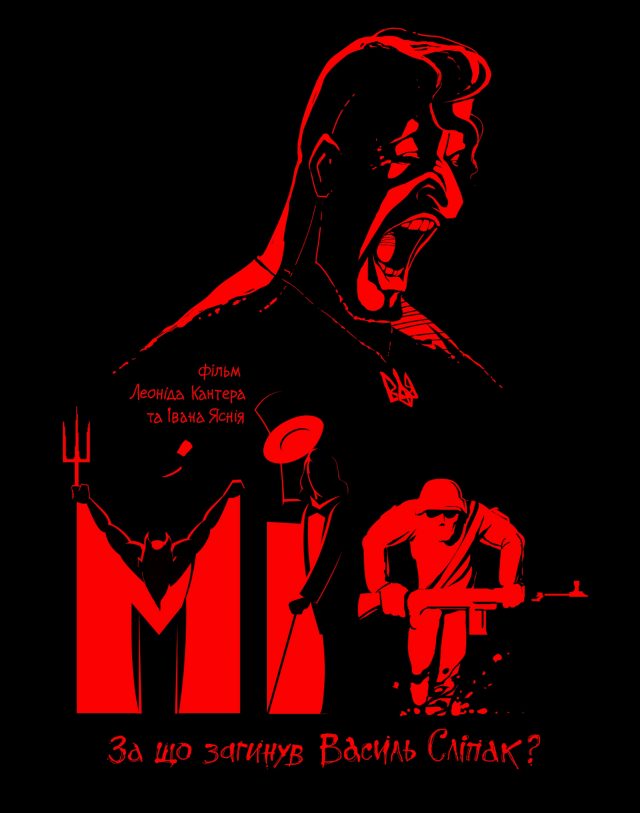

But despite the film’s title, the co-directors Leonid Kanter and Ilya Yasniy abstained from overt mythmaking. Instead, they created a nuanced, multifaceted profile of Wassyl Slipak, the Ukrainian opera singer who abandoned his life in Paris to fight and, ultimately, die for his country.

The result is an unexpectedly touching, at times meditative reflection on both Slipak himself and the nature of sacrifice and war.

Born in 1974 in Lviv, Slipak demonstrated remarkable vocal talent from an early age. He studied at the Lviv Conservatory, and then joined the Paris National Opera. Slipak’s unique voice and his theatrical manner made him a star of the opera world.

Then, in 2013, demonstrators took to the streets of Kyiv to protest President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision not to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union. They were met with armed force from the country’s security agencies.

Slipak felt called to return home. However, due to his contract with the Paris National Opera, he could not simply leave for Ukraine. Instead, he became a Euromaidan activist in Paris, gathering donations for the protesters and later for the military. He even began wearing the traditional Ukrainian chupryna Cossack hairstyle.

Eventually, he took leave of the opera and returned to Ukraine to fight in the Right Sector battalion’s Voluntary Ukrainian Corps. There he chose the nom de guerre “Myth,” a reference to the character of Mephistopheles from the Faust opera.

After a tour in the Donbas, Slipak returned to the stage in Paris. But something about the war had altered him as an person. Going against the advice of friends, he eventually re-joined the war effort. On June 29, 2016, he was killed by sniper fire near Luhanske in Ukraine’s Donetsk region. President Petro Poroshenko posthumously awarded him the title of “Hero of Ukraine.”

On its own, Slipak’s story is a fascinating tale of how the Euromaidan revolution and the War in Ukraine changed the lives of Ukrainians. But in the hands of Kanter and Yasniy, it becomes something much more. Although both directors are clearly motivated by patriotism, they avoid falling into nationalism’s worst traps. Their portrayal of Slipak and the people around him is complex and deeply humane — even when covering politically fraught territory.

The film includes extensive interviews with Slipak’s ex-girlfriend Liza, who appears to be from Russia. In essence, the opera singer chose the Ukrainian armed forces over her, a decision that she cannot entirely comprehend. Yet instead of the potential political significance of the decision, the directors focus on the human side of the story.

The documentary presents Slipak as an over-the-top, maximalist personality. Yet it also does not shy away from his shortcomings. Soldiers in his battalion admit that he probably wasn’t the best fighter in the group. Friends admit to not entirely understanding his decisions.

A parallel narrative — based on Italian author Gianni Rodari’s 1958 children’s book “Gelsomino in the Country of Liars” — gives the film a philosophical message. “Myth” begins and ends with Parisian children sitting in a classroom and listening to their teacher read the book, which tells the story of a boy who uses his loud voice to call down the lies of a pretender to the throne.

There’s an inherent comparison in the fable: Gelsomino was able to save the Country of Liars and drive out the autocratic ruler. Slipak lost his life, but Ukraine’s is not yet saved.

However, the most chilling moment of the film comes near the end. When Slipak was hit by sniper fire, one of his comrades-in-arms had a camera running. While we don’t see Slipak being shot, we do see the other soldiers’ frantic and ultimately unsuccessful efforts to resuscitate him.

Taken as a whole, “Myth” transcends a simple profile of Slipak or a war documentary. It forces the viewer to confront the grim realities of armed conflict and the human sacrifices it requires.

The directors clearly admire their protagonist, yet they demonstrate a humility often lacking in patriotic art. Instead of telling us that Slipak’s sacrifice was right, they are content to simply pose the question and let us answer it ourselves.