This essay forms the core of the book “Orwell & The Refugees: The Untold Story of Animal Farm”

“If you look into your mind, which are you, Don Quixote or Sancho Panza? Almost certainly you are both. There is one part of you that wishes to be a hero or a saint, but another part of you is a little fat man who sees very clearly the advantages of staying alive with a whole skin. He is your unofficial self, the voice of the belly protesting against the soul.”

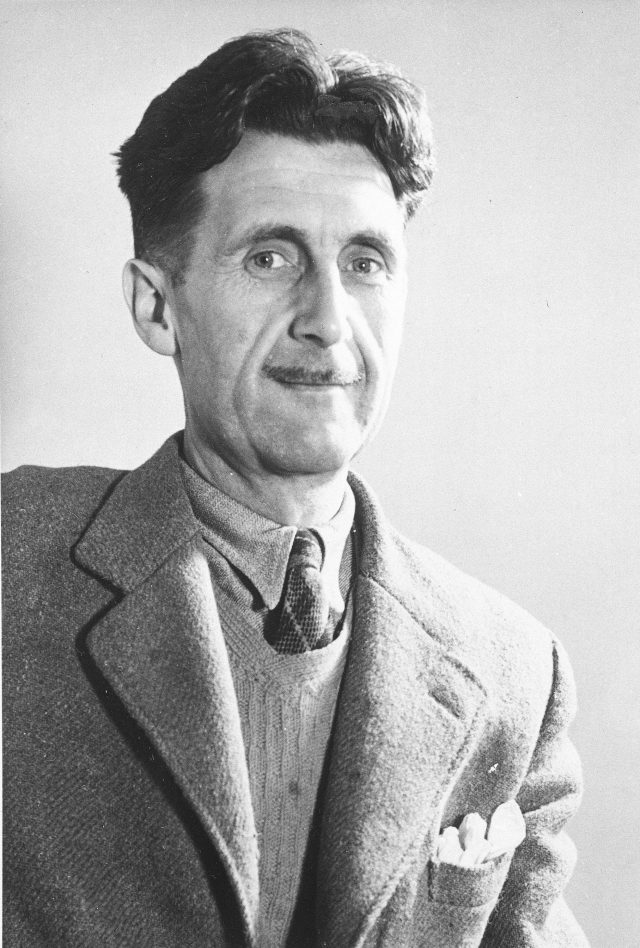

— George Orwell, essay, “The Art of Donald McGill”

My grandfather Olexji liked to tell my mother this fable about a wild man:

A ship of missionaries anchors off an island. Scouting the seemingly uninhabited island, the missionaries come across a wild man jumping over logs and screaming at the top of his lungs. When the missionaries ask him what he’s doing, the wild man responds that he’s worshipping God.

“No, no, that’s not how you worship God,” says a missionary. “We will stay with you and teach you the Lord’s Prayer.”

So they stay with him and teach him how to pray, and after a few days, they set sail for the next island. Soon they spot an object on the water approaching their ship. As it gets closer, they see that it’s the wild man, running towards them on the water, screaming, “Fathers! Fathers! I forgot a verse!”

As the missionaries stare, open mouthed, one finally says, “No, it is you who must teach us.”

This fable sums up George Orwell. He was the wild man worshipping truth in self-imposed isolation. He lived in wretched clothes he defiantly wore to mock “polite society,” with its wars and shallow caste system. His convictions, eventually, defied orthodoxy. And like that wild man, there were likely horrible things we never got to learn about Orwell, the reluctant saint.

“Every life viewed from the inside would be a series of defeats too humiliating and disgraceful to contemplate,” said Orwell, who famously demanded in his will that no biography ever be written about him.

The truth about Orwell, or any individual as he himself points out, is complicated. There was Orwell the womanizer who enjoyed prostitutes when he lived in Burma and cheated on his first wife and muse Eileen O’Shaughnessy—a talented poet whose poem “End of a Century, 1984” and love for making up stories about farm animals are said to have influenced her husband’s two greatest novels; there was Orwell the privileged tramp who had the safety net and support of his family to fall back on; Orwell the attempted rapist, according to an account by his childhood friend, first love, and intended victim, Jacintha Buddicom. And the list can go on about what an aggressive, disagreeable, contradictory person Orwell was. If you meet your idols, prepare to be disappointed.

Much like the freedom enjoyed by the wild man, Orwell’s self-imposed isolation was necessary. “Between the ages of about 17 and 24 I tried to abandon this idea [of being a writer], but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books,” he explains in his 1946 essay Why I Write. The fact that Orwell chose a life of poverty in order to pursue writing is a well-known aspect of his legend. One biographer, in particular, as though determined to expose this “saint of the left,” seemed to relish pointing out that when he was down and out in Paris and London, Orwell’s family regularly sent him money. Even those who knew Orwell personally, like the anarchist writer George Woodcock, acknowledged that though Orwell dressed like a tramp, his mannerisms and accent exposed that he had gone to Eton—arguably the most prestigious boys school in the world. Yet Orwell gravitated to the fringes of society, for that was where he was most comfortable—and free.

After giving in to his nature and becoming a writer, he shared the painful consequences of choosing a life of poverty in his anxious third novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying. Full of wrenching details describing an impoverished life, it’s about a man who leaves his comfortable job at an ad agency and works in a bookshop in order to have the time to write. It was Orwell’s protest against materialism. Like his tragic hero, Orwell worked in a bookshop when he first began taking writing seriously.

For the last decade of his life, he lived in declining health and modest means, subsisting on writing book reviews and articles. An on-air gig at the BBC in London from 1941 to 1943 did not last long, because he wanted to stop delivering what he viewed as propaganda. In fact, he was actually producing top-notch programs on literature, science, and psychology with leading thinkers. Unbeknownst to him, he was being considered for a raise just before he quit. Orwell’s short time at the BBC was indeed prolific. But with the war, government censorship of the media was in full effect, and Orwell left to finish Animal Farm, an expose of England’s important ally, the Soviet Union.

“What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing an art,” he stated in Why I Write. “Looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.” He goes on: “Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole.”

With Animal Farm, Orwell exposed Stalin and the Soviet Union at a time when to do so went against the prevailing ignorance. American capitalism had experienced a great moral crisis in 1933 when it embraced doing business with Stalin just after the mad dictator had intentionally starved to death an estimated 6 to 10 million of his own citizens. We will never know the exact number of victims, and that is part of Stalin’s crime. Influenced by the blatant lie filled “reporting” of Walter Duranty, the Pulitzer Prize– winning Moscow bureau chief of The New York Times, Western governments turned a blind eye to Stalin’s genocide. Duranty swept it under the rug with a media cover-up that he orchestrated.

Despite the ideological differences, the titans of U.S. industry salivated over the prospect of selling to the Soviet Union. To modernize his massive nation, Stalin paid for services and equipment by selling 1.7 million tons of grain to the West; of course Stalin had so much grain to sell because he seized it from Ukraine—the breadbasket of Europe—effectively starving to death millions of Ukrainians in the terror famine known as Holodomor. Stalin also wanted to break the collective back of Ukrainians, since they had fought for their independence during the Russian Revolution and were nationalistic.

When Stalin’s approval rating in the West was at its highest, thanks to cheerleaders like Duranty and George Bernard Shaw, he had already become the vilest mass murderer in history. Stalin’s genocide is a shocking tragedy; if he had been held accountable, it would have sent a message to future evil dictators. If the West had brought Stalin to justice, Hitler would have been shown that he would not be able to get away with his “Final Solution.” Instead, Hitler began building his first concentration camp in 1933, on the heels of Stalin’s genocide famine—a news story in Germany during Hitler’s rise to power.

Unfortunately, justice was made impossible due to a Western media plagued by corruption and censorship. During Orwell’s time, all information was tightly controlled by a small number of reporters and editors, many of whom curried favors with the Kremlin. These were the wind- mills Orwell quixotically fought against. It drove him to help others read through the lines of the mainstream media. His articles, essays, and books aimed to rub the fog off the rosy glasses of a generation enamored with Stalin’s strength, confusing it for the hopes and dreams of the Russian Revolution.

Out of respect for (and fear of) Stalin, Animal Farm was rejected by four publishers, including his usual go-to Victor Gollancz. Jonathan Cape agreed to publish it then backed out after consulting with “an important official in the Ministry of Information” who, unbeknownst to him, was a Soviet agent. Cape claimed Stalin wouldn’t like it. Orwell joked in a letter to a friend: “Imagine old Joe (who doesn’t know one word of any European language) sitting in the Kremlin reading Animal Farm and saying ‘I don’t like this.’”

T.S. Eliot, on behalf of Faber & Faber, wrote a letter lecturing Orwell on being too hard on Stalin; Eliot called the “public spirited” pigs best qualified to run the farm.

In his essay, “Freedom of the Press,” Orwell exposed the media’s self-censorship. He wanted this essay to be the introduction to Animal Farm, but the small publisher that played savior, Secker and Warburg, thought it best to leave it out. They did not want to court any more controversy; for even the wife of Frederic Warburg tried to stop her husband from publishing the book, out of gratitude to the Red Army. In the end, Animal Farm did not come out until after the war — August 1945.

Orwell must have known what message he was sending by continuing to dress like a tramp after the success of Animal Farm, his first literary and commercial hit. Dressed as an urban wild man in ragged old clothes, Orwell’s political conviction notoriously extended to his wardrobe. “Clothes are powerful things,” he wrote in Down and Out in Paris and London, where the right jacket could hide an empty stomach and desperation for a job, any job. His friend Woodcock writes: “John Morris, who disliked Orwell as a result of their association at the BBC, suggested in Penguin New Writing that this sartorial eccentricity manifested a childishly self-conscious rebellion against the proper standards of polite behavior.”

Polite behavior, Orwell knew, could mask the vilest cruelty. Witnessing the absurd injustices of the caste system while growing up in India and serving in Burma as a police officer, Orwell felt compelled to turn his passionate experiences into prose that would change the world. “Our job is to make life worth living on this earth, which is the only earth we have,” he wrote in Reflections on Gandhi, published in 1949 just before his death.

As a writer, he longed to create heaven on earth by ending injustices by exposing uncomfortable truths. His mind was his weapon, as exemplified by Winston daring to keep a journal in the Thought Police world of 1984. He was a novelist with a reformist spirit, an activist for common sense. He even changed his name from Eric Blair to George Orwell, so as not to embarrass his parents. His pen name celebrates his love of nature, namely the English countryside: George is the patron saint of England, and the River Orwell was a favorite retreat.

As a novelist, Orwell was clearly first and foremost a social critic. The majority of his novels are journalistic rather than dream-inducing page-turners. (He referred to himself as a pamphleteer—one who prints and distributes one’s political convictions, a popular activity during World War II and an early form of blogging.) In Down and Out in Paris and London, Orwell, after many pages painting a gripping destitute world, speaks directly to the reader about why the luxury industry must cease to exist. He argues that if only people would accept that money does not buy happiness, then the poor souls stuck in the worst jobs of the hotels and restaurants of Europe would no longer be trapped in indentured servitude. In the middle of a cinematic adventure, Orwell speaks directly to the camera.

Immediately after Animal Farm, Orwell began working on another book, writing, “It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I do know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write.”

That book was 1984. Orwell wrote it in a passionate frenzy right before he passed away. As he lay dying from tuberculosis, at the young age of 46, Orwell protested that he still had more books in him. It’s up to us to continue writing for him; there’s too much at stake not to continue his fight for heaven on earth.

Andrea Chalupa is a writer, journalist, and producer in New York. Andrea helped launch online video for Condé Nast Portfolio and AOL Money & Finance. She oversaw the translation of her grandfather’s Soviet memoir about growing up under Stalin and his years as a tortured political prisoner in a secret NKVD prison.