A well-known American author, translator and scholar of Russian and Jewish literature muses on what it means to emigrate and to live and write translingually while inhabiting several linguistic cultures at once. The concept of translingualism stands for words and other aspects of language that are relevant or similar in more than one language. Thus to be “translingual” may mean “existing in multiple languages” or “to have the same meaning in many languages.”

I understand the predicament of being a bilingual writer. But I’m still not quite sure what it means to live and write translingually. Both rootless and rooted at once, translingual writers are supposed to work not in one language but in several at once, and not always simultaneously. Yet even in the not so recent the past, translingual writers used to exist all by themselves: artistically homeless and culturally stateless. Does literary translingualism mean that one is betwixt and between, both here and elsewhere? Think of the aloneness of Joseph Conrad in English, Samuel Beckett in French, of Paul Celan in German, Rachel Bluwstein in Hebrew. Is a translingual writer who’s found a new home no longer writing in transit?

Let me turn, briefly, to the story I know best and sometimes call my own, that of ex-Russians—and ex-Soviets—writing in English. When the Russian diplomat Pavel Svin’in (Svenin) lived and published in Philadelphia in the 1810’s, he was most certainly in a league of his own. When Abraham Cahan, the legendary editor of the Forward, and a Russian- and Yiddish-speaking immigrant from the Russian Empire, was learning to write fiction in English in the 1900’s, he, too, had few worthy interlocutors. The St. Petersburg-born Vladimir Nabokov also had few translingual colleagues when he arrived in America from France in 1940.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, many more writers came to the US and Canada from the USSR, riding the wave of the Jewish emigration. These new translinguals—Joseph Brodsky most famously—often felt strapped for style and voice as they forded the Hudson and the St. Lawrence. It has taken at least a generation for Soviet immigrants to find their literary bearings in the New World, and perhaps even longer to form a truly translingual neighborhood—a community—both in their own eyes and in the eyes of the American (and Canadian) cultural mainstream. Many of today’s translinguals—the Leningrad-born Gary Shteyngart, the Moscow-born Anya Ulinich, the Minsk-born Boris Fishman, the Odessa-born Yelena Akhtiorskaya, the Tashkent-born Vladislav Davidzon (editor of this magazine) and others—left the former Soviet Union and its successor states as children or young people. They have their literary great-uncles and great-aunts on both sides of the Atlantic. Representatives of this new wave of American and Canadian translingualism write in English as they hearken back to Isaac Babel, Vasily Grossman and llya Ilf & Evgeny Petrov, but also to Bernard Malamud, Philip Roth, S. J. Perelman and Mordecai Richler. They have translingual literary lovers and partners, friends and next-door neighbors. This doesn’t diminish the fun of today’s translingual literary commerce, but it does make it more of a Russophone—Russian-American and Ukrainian-American—family business, and also something of a community affair. “Whither shall we sail?” Pushkin might ask, if had he been Jewish, had immigrated to the US and mastered the English language.

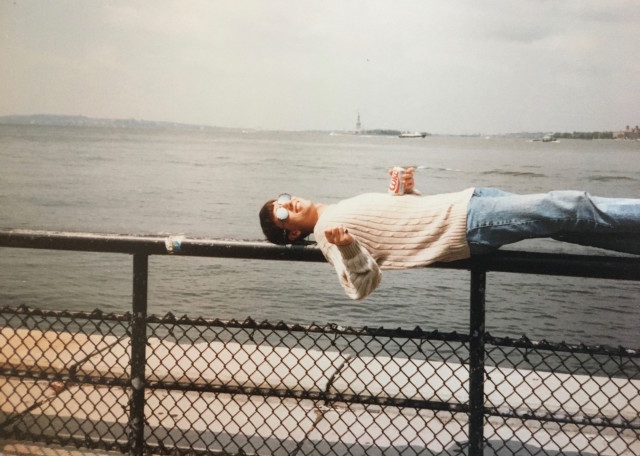

In my book Waiting for America: A Story of Emigration, mainly set in Italy in 1987, a 20-year-old exile from Moscow discovers stories and novels by émigré authors. Back then, the black sand of a seedy Tyrrhenian public beach in the town of Ladispoli was my open-air reading room, and I read Russian-American translinguals as I contemplated living in the New World. Five months later, on a wet November afternoon, I walked across the campus of Brown University and knocked on the office door of the writer John (Jack) Hawkes. Hawkes was a legendary American postmodernist, the most famous writer on the Brown faculty, and I desperately wanted to take his fiction writing seminar.

Silver-haired, witty, verbally perverse, Hawkes listened to my rambling account of leaving Moscow, writing poetry and fiction in Russian, and coming to the US as a refugee. He waited, silently, lips twitching, then asked:

“Have you read Nabokov?”

Hawkes pronounced the second “o” in Nabokov’s name with an extra roundness, as if caressing the stressed Russian vowel.

“Nabokov?” I asked, in disbelief. “Yes, I have.”

“He’s remarkable,” said Hawkes, who was preparing to retire from Brown the following year. In 1965 his novel Second Skin competed with Nabokov’s The Defense and Bashevis Singer’s Short Friday for the National Book Award for Fiction. Saul Bellow’s Herzog ended up taking the prize.

Hawkes had no interest in refusenik politics and no ear for immigrant anxieties. Yet he let me into his last fiction seminar. In the spring of 1988, a translingual novice surrounded by aspiring Brown writers—all of them American-born—I tried my hand at composing in English. Almost thirty years later, I’m still discovering the pleasures of writing in tongues.

Maxim D. Shrayer is the author, most recently, of “Leaving Russia: A Jewish Story” (in English) and “Bunin and Nabokov. A History of Rivalry” (in Russian). He is Professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies at Boston College.