The recently published “Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine” by Mayhill C. Fowler (University of Toronto Press, 2017) details the transformation of the cultural landscape (and theater production and reception, in particular) that took place on the territory of present-day Ukraine from the late Russian Empire, through the Civil War and early decades of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The story, which takes place nearly 100 years ago, remarkably resonates with the challenges Ukrainian artists and cultural actors face today, as they struggle to establish adequate conditions for the production and reception of their work in independent Ukraine. At the same time, it provides a much-needed historical foundation from which to analyze the chronic problems in the Ukrainian cultural sphere. This piece was written by the Ukrainian-American Larissa Babij, The Odessa Review’s theater critic.

I moved to Ukraine from the United States after the Orange Revolution. Within a few years, I was engaged in the emerging local contemporary art scene, testing out the ways in which the bonds of community could serve as a substitute for institutions. By 2011, people I had known separately — the artists of the R.E.P. group, performers of TanzLaboratorium, art managers trained at the Soros Center for Contemporary Art, and certain forward-looking curatorial staff of the National Art Museum of Ukraine — were crossing paths more frequently and working together more closely. Often these collaborations took place informally.

What drew us together was concern for the cultural landscape of Ukraine, an interest in experimental art practices, and a desire to shift modes of presentation and discussion of art away from old fashioned Soviet customs. We understood that if we didn’t exercise our individual agency in public space to talk about and defend our interests, the Ukrainian culture infrastructure would keep serving the ideologically capricious state, image-conscious oligarchs, or the entertainment industry, but not us — the artists.

It was exciting living in the midst of constant crisis with a small circle of collaborators (some of whom became my closest friends) available at any hour to discuss the issues that troubled me. As long as I had a place to sleep and food to eat, it seemed possible and necessary to maintain a practice of looking, listening, thinking, speaking, and acting in the public sphere indefinitely. But sooner or later the past catches up with you. The conditions in which we were working, which were rooted in events and cultural developments of nearly a century past, proved more powerful than our individual words and actions. And the choices and priorities of various members of our circle began to coincide less and less.

Fowler’s book reconstructs the historical conditions that shaped the Ukrainian stage, leaving the cultural legacy we encounter today. Based on a decade of meticulous research in documents in Russian, Ukrainian, Polish and Yiddish, it presents us with the complex and multidimensional story of the formation of the Ukrainian SSR through the interrelated efforts of artists and officials. This history of the theater begins in the borderlands of late imperial Russia (with its many cultural centers) and advances through the early decades of the Ukrainian socialist state, showing how Soviet policies began to centralize political and cultural power in Moscow by the 1930’s.

The narrative of this important historical work simultaneously follows the lives of individual actors (the theater director Les Kurbas, playwright Mykola Kulish, arts official Andrii Khvylia, among others) and the transformation of cultural infrastructure (and policy) as the new Soviet state emerged and solidified its methods for controlling the lives of its citizens. Intricate, semi-formal social networks — shaped equally by personal ties and official roles — influenced the creation of artistic works which were more than merely reflections of a particularly tumultuous time, but also invested in shaping the emerging Soviet Ukrainian culture.

Today, to speak of the Ukrainians Kurbas and Kulish as peers of Moscow-based artists such as Solomon Mikhoels and Mikhail Bulgakov requires both acknowledging the bias toward Moscow that prevails in Western scholarship of Soviet culture and elucidating how this perspective was formed. “Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge” is a reminder that high-quality art was being produced by people of various ethnicities in multiple languages outside of Moscow in the early decades of the Soviet Union. But it also shows how that work slowly lost status in relation to Moscow, in the process actually becoming less compelling as artistic experimentation gave way to the dictates of state policy.

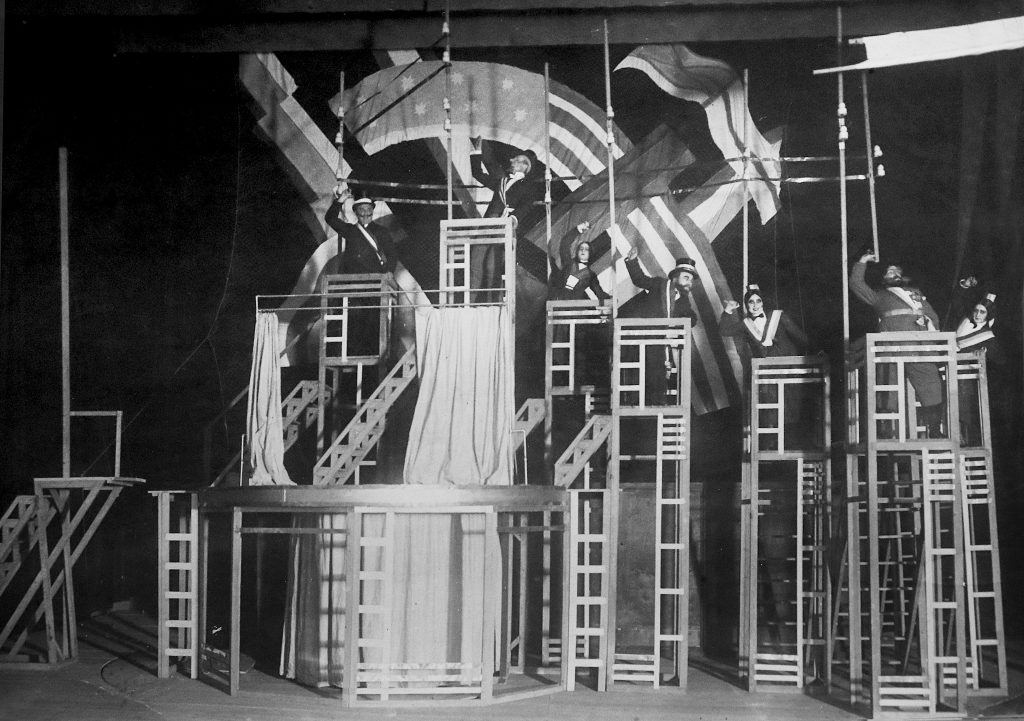

This project requires reconstructing Ukrai ne’s multiethnic cultural landscape at the turn of the 20th century — where theater was performed in Ukrainian, Yiddish, Polish and Russian — to demonstrate how those conditions led early Soviet artists and activists to make their decisions while shaping early Soviet cultural policy. Although theater flourished in late imperial Russia along established networks, Fowler notes, “actors, dependent on the whim of fickle audiences and philistine patrons for survival, could be stranded by entrepreneurs and left destitute in a remote village”. Early Soviet artists, convinced of the importance of their work to further the socialist project, demanded that the state guarantee their livelihood and provide the resources for enacting their artistic agendas, including audiences. Initially, they were successful: “Kulish, [Ostap] Vyshnia, and Kurbas all depended on state institutions, and all worked with state institutions, to make art”. Artists in the Soviet Union enjoyed social prestige, and as long as they were connected with and valued by the state apparatus, they were generously supported — given space in which to rehearse and show their work. These artistic elites were also provided with apartments, often in central and desirable neighborhoods.

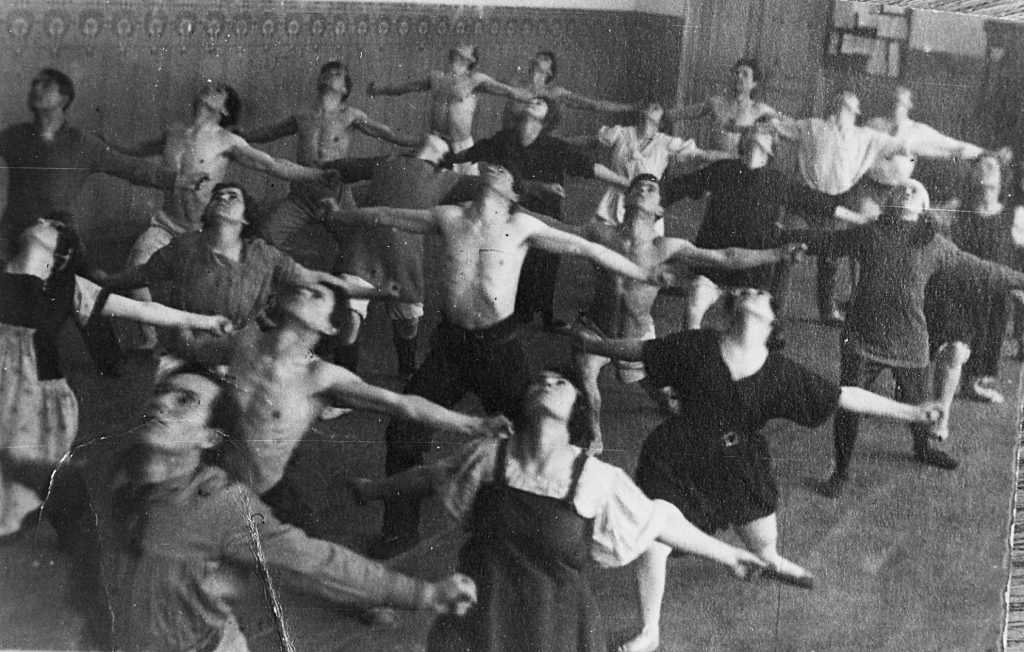

To someone who has tried to survive while pursuing artistic work in the 21st century (Fowler was a professional actress before embarking on her career as a historian), the investment of the early Soviet state in cultural production is incredible. Work in the arts is dependent on access to resources, which in today’s world are often scarce. Rehearsal space is rented by the hour; contracts regulate work hours and overtime pay; art workers need additional jobs to support themselves. In contrast, certain early Soviet theaters would regularly exceed their annual production budget, and would receive more funding the next year. The production of quality artistic works, considered valuable to the project of developing the new socialist state, was more important than the ability to manage allotted resources. The 1920’s were a fruitful period for art, theater, and literature in Soviet Ukraine. Artists experimented not only with the forms their work would take when demonstrated before an audience, but with the ways in which that work would be produced. The artists were living and socializing together. The space of artistic work, ideological debate, political and personal life overlapped to a considerable degree, allowing ideas to ferment in an amorphous space.

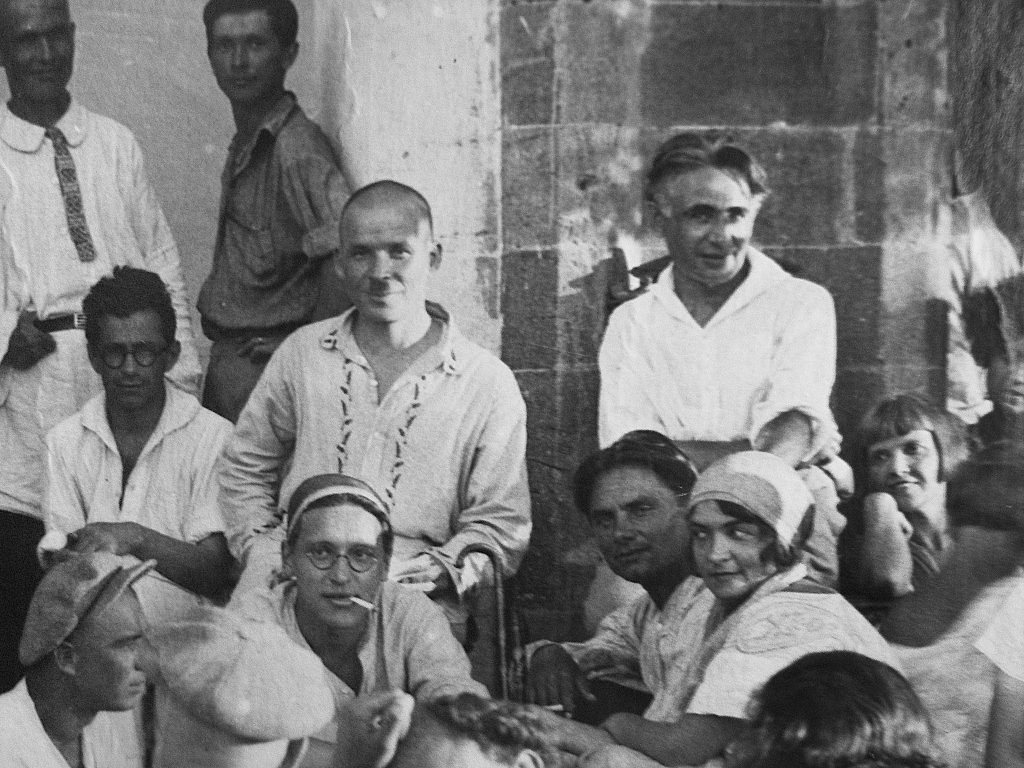

In 1920’s and 1930’s Kharkiv, artists, writers, and officials frequented the same cafes and billiard halls, and later inhabited the same residence for writers, Budynok Slovo [House of the Word]. Bound by ties both personal and official and driven to develop a particular Soviet Ukrainian culture through their art and influence, these elites represented the “beau monde” of the book’s title. While the term may conjure up images of Paris cafes and salons, Fowler points out that in the early USSR, “art was discussed in the state apparatus, in state-owned apartments, or in the editorial boards of state-owned newspapers, among other locations frequented by state officials as much as by artists”. This aspect of early Soviet Ukrainian culture, where a blurring of official capacities and personal relationships informed public artistic expression, was codified in the interdependent roles of “official artist” and “arts official”, a legacy that lives on in Ukraine (and other post-Soviet states) to this very day. Fowler claims, “the structural change of the arts and artists absorbing into officialdom was not imposed by Stalin, but rather resulted from a transformed relationship between artists, officials, and the larger public during the years of civil war and early building of socialism”. Her story shows how the zealous desire to create a new culture for Soviet Ukraine produced an all-pervasive state mechanism that destroyed the very men who brought it into being.

This book challenges the debates that pit Ukrainian culture against the Soviet system. According to Fowler, “[t]he beau monde created Ukrainian culture in a Soviet context, and that Soviet layer was not imposed from above, but… was part of the mentality of the young elites making early Soviet culture”. Ukrainian artists valiantly took on the challenge of creating a culture both Soviet and Ukrainian, and the most fruitful period of cultural production and experimentation in art coincided with on-going debates on the irresolvable problem of what that “Ukrainian” content might be. The new Ukrainian cultural elites had been elevated to their positions by the revolution and they were deeply invested in the socialist project. Fowler insists that the work (and legacies) of Kurbas, Kulish, and their compatriots must be examined in the context of the early Soviet Ukrainian project. For her, valorizing these artists without acknowledging their ideological bias means ignoring a very significant aspect — and the revolutionary fervor — of their work.

Arriving in Ukraine after the Orange Revolution, I noticed how much the work of young critical contemporary artists was directly aimed at exposing current social and political conditions with an eye toward change. These artists were using their creative energy and public visibility to make up for the shortcomings of civil society and to help Ukrainian society transition from one ideological system to another. Fowler’s description of the tireless men gathered around Mykola Kulish’s kitchen table makes me pause:

“‘Ostap Vyshnia, who kept his hands in his pockets and complained of rheumatism until Kulish poured him a vodka; Pavlo Tychyna, the lone vegetarian for whom [Kulish’s mother-in-law] made onion-filled dumplings; and Mykola Khvyl’ovyi, who ‘smoked non-stop and could never sit peacefully in one place.’ These men felt ‘full responsibility for the future of the new art,’ and believed that it was up to them to make culture for Soviet Ukraine”.

I myself remember countless evenings and nights in somebody’s Kyiv apartment, sitting around — now with laptops and video cameras — discussing urgent cultural matters (like the appointment of a politician’s wife as the director of the National Art Museum or the dramatic censorship of a con-temporary artwork by the director of the Mystetskyi Arsenal) and immediately formulating a collective statement or planning a public action. Why had it never occurred to me, while dealing with the endless stream of urgent problems related to Ukrainian culture, that we were following in the footsteps of the artists of 1920’s Kharkiv, where art and life intermixed and work involved both the production of art as well as the construction of the infrastructure to support and display it? I found numerous parallels in this story with my own youthful participation in collective efforts to shape contemporary Ukrainian cultural policy, institutions, and community.

“Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge” maps a transition from desiring, demanding, and creating stable conditions for making and showing artistic work to that of a system where the state and the arts were so deeply intertwined that not only the work produced but also the lives of the artists themselves became accountable to the state. Within a decade, the fervent experimentation of Kharkiv’s Literary Fair was subsumed into the excruciatingly organized world of the Soviet Union of the 1930’s, with its vast network of informers and interrogators (and prison labor camps). It was a world in which an entire artistic or theatrical circle could be executed when one fell out of favor with the authorities. Thus, it becomes clear how the desire to radically change the circumstances one was shaped by can produce other no less (or even more) threatening conditions — ones with the power to destroy a career and life, and even obliterate one’s historical legacy.

In the early 2010’s, it seemed that Ukraine’s long official tradition of nurturing ideological art in the service of the state had little to offer as a foundation for a new independent Ukrainian culture that might support and appreciate critical artworks. Members of the local contemporary art community looked further afield, traveling to Europe, reading in English, constructing a hybrid heritage in the international tradition of contemporary art. Without exactly disregarding the past, we didn’t peer at it too closely, either. We shared with our early Soviet Ukrainian predecessors an expansive and primarily forward-looking gaze. Kurbas, Kulish, and Khvylovyi looked to their modernist contemporaries in Europe for inspiration for their new Ukrainian socialist art rather than to Moscow and Russia. Theirs was a speculative attempt to create culture both Soviet and Ukrainian, based on dreams for a different future. Could it be that even then, their past caught up to them sooner than they expected — and with tragic results?

“Re-communizing” Soviet Ukrainian theater means reinstating the works and lives of Kurbas, Kulish, and their contemporaries in the context in which they created their works. It means returning to their legacies with the understanding that they were driven by intentions to produce art that would help shape the new Soviet Ukrainian state and bring their socialist dreams into fruition. It also means acknowledging that their stories were first obliterated from memory by the very state that they helped build and only later reconstructed through painstaking scholarly research.

As Fowler’s story advances into the 1930’s, becoming more complex and convoluted, she comments as a historian on the trickiness of using the transcripts of interrogations as source material. Of course, it is impossible to know who really authored a confession or the degree to which the interrogator or interrogated influenced its formulations. As Fowler has learned through extensive archival research, while testimony given under interrogation cannot be taken at face value, it can offer insight into actual relationships, activities, or even political views. Ultimately, “[t]he documents themselves speak to a certain kind of truth because they reveal the way that officialdom functioned, how they exercised incredible authority over artists’ lives, and how connected the secret police was with artists”. This heritage is one that we have to contend with today, and this book offers a courageous counterpoint to the Ukrainian state’s attempts in recent years to shape “national memory” into something unambiguous and ideologically biased.

“Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge“ is a tribute to dreamers, and to those who believe that one’s actions can change the world. It is also a story of failure and an unflinching testament to the monsters that dreams can unleash: “That the Soviet state murdered Kurbas and Kulish in November 1937 is a tragedy… The tragedy lies not only in the state violence, but also in the failure of the monumental task these artists set before themselves. They aimed to change the theater, and from theater the world — and nothing less”. But the book does not end with the tragic deaths in the Gulag of Kurbas, Kulish, and thousands of their fellow Ukrainian revolutionaries and artists (among millions of their fellow Soviet citizens). Fowler carries the story beyond the 1930’s, demonstrating how “the culturally rich Russian Imperial Southwest would become the Soviet cultural periphery”. As power became more centralized in Moscow, Ukraine’s imposed provinciality was emphasized in cultural policy and official decisions that favored stereotyped ethnic tropes over sophisticated work as a reflection of national culture.

Fowler’s unique perspective — based on over a decade of scholarly research and a previous acting career — makes “Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge” not unlike an evening at the theater. The actress-turned-historian invites us, the readers, to look upon the collection of stories and events that she has so painstakingly arranged as material for invoking personal memories and connecting with our own experiences. The book challenges Ukrainian cultural practitioners and scholars — both subject to the country’s weak and dysfunctional infrastructure and work-ing to set up conditions that would be more conducive to critical thinking and artistic reflection in the 21st century — to look hard at this story and interrogate the connections between it and our own endeavors. This requires addressing the complicated heritage of our ruptured artistic tradition — accepting that our national cultural heroes, who were deeply invested in Ukraine’s future, were co-authors of the Soviet project in all its brutality; acknowledging the dangerous power of dreams divorced from memory; understanding that culture develops gradually — and never from a clean slate. Dancing between biographical sketches, historical narrative, and an analysis of the changing cultural infrastructure from late imperial Russia through the first decades of the Ukrainian SSR, the book demonstrates that history is as much a personal matter and responsibility as something contained in books and official narratives.

Larissa Babij is a Ukrainian-American writer based in Kyiv. She translates and writes about contemporary art in Ukraine.