Since 1997, the intellectual journal Krytyka has projected an alternate future program for Ukraine: democracy, openness, internationalism. For twenty years, The journal has been a “must read” for anyone interested in the intellectual side of the development of contemporary Ukrainian culture.

Since 2014, that vision of the country has gone mainstream.

When Julia Bentia was studying in Kyiv’s Tchaikovsky National Music Academy during the mid-2000’s, all her professors read and wrote for one publication. They also recommended it to their students.

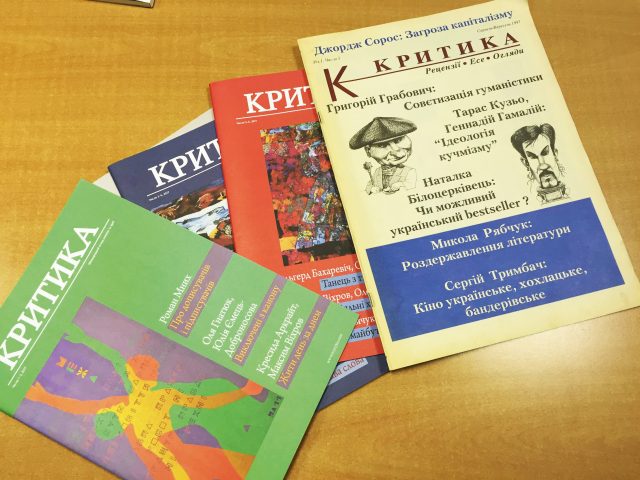

That was how Bentia got her start reading Krytyka, Ukraine’s premier intellectual journal. Founded in 1997, Krytyka has grown into many things. First and foremost, it is a platform for discussing and debating the most important artistic, social and political issues in Ukraine.

But as Bentia discovered, the journal also constituted a community — a publication that unites scholars, intellectuals, artists and others interested in indepth analysis of the challenges facing their country. In 2016, after a decade of reading Krytyka, Bentia became its executive editor.

Now, as Krytyka marks its 20th birthday, she and her colleagues are working to chart the publication’s future in a changing Ukraine.

“For me, [Krytyka] was always a platform where you could talk about important issues and serious publications. Krytyka always kept its eye on the humanities”, she says. “Now, it’s important that we keep the focus on things like constitutional reform”.

On Two Shores

Long before it’s foundation, Krytyka existed as an idea in the mind of George Grabowicz, the Dmytro Chyzhevs’kyj Professor of Ukrainian Literature at Harvard University. While leading Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI) during the early 1990’s, Grabowicz worked to establish contacts with Ukrainian scholars. Ukraine had just gained independence in 1991, and HURI was actively involved in the process of bringing the country’s academia up to speed “after the dark night of Sovietism”, he explains.

When his term as HURI director ended in 1996, Grabowicz got further involved with Ukraine. Initially, he considered creating a Ukrainian-language publication that would be an extension of “Harvard Ukrainian Studies”, HURI’s journal. But soon he realized that what Ukraine needed was not a purely academic journal, but something with a broader public resonance.

“The implicit model for me was always the New York Review of Books, that I read, admired, and thought was a journal of intellectual horizons”, Grabowicz says. He particularly appreciated that publication’s ability to cover a broad range of topics — from literature to politics.

Cooperating with Ukrainian colleagues such as the public intellectual Mykola Riabchuk and the late writer and literary critic Solomiya Pavlychko, Grabowicz launched Krytyka in August 1997. The first issue — whose design suggested a clear homage to the New York Review of Books — featured an article on the “Sovietization of the Humanities” by Grabowicz, a text on the ideology of then President Leonid Kuchma, and an essay on Ukrainian film. In another article featured on the cover, Ukrainian poet Natalka Bilotserkivets asked, “Is a Ukrainian bestseller possible?”

That eclectic mix — arts, politics, and the politics of art — made Krytyka a hit in Ukrainian intellectual circles. After putting out two issues in 1997, Krytyka went monthly. Then, in 1999, it also became a publishing house.

“In the course of 17 years, we have published over 200 books”, says Grabowicz, who serves as Krytyka’s editor-in-chief. “Many of those were translations of other publications that we felt were also important to do in Ukrainian. But many were new — especially various projects related to Ukrainian intellectual history”.

Changing Ukraine

Implicit in Krytyka’s mission are efforts to push Ukraine towards democracy and reform. In 2017, these are widely seen as key goals by all sorts of people across the country, but they were important for the journal from the beginning.

When he founded Krytyka, Grabowicz hoped it would be a platform for initiating projects that Ukraine’s established academic institutions were uninterested in pursuing. For example, Krytyka has already published seven volumes in a projected 35 volume series of the complete works of 19th century Ukrainian writer, critic and folklorist Panteleymon Kulish.

“That may sound very specific, but initially, for me, Krytyka was meant to be a kind of project that would be the basis of a renewed Ukrainian Academy of Sciences”, Grabowicz says.

That didn’t happen the way Grabowicz hoped. Twenty years later, the Academy of Sciences remains largely unreformed since the Soviet days, so Krytyka has often had to proceed alone.

If one needs an example, one only needs to take the case of reforming the orthography of the Ukrainian language. During the Soviet period, the authorities altered the language’s vocabulary and orthography to bring it closer in line with Russian. In the early 1990’s, some minor reforms were made in the opposite direction, but they largely left the Russified standards in place. Finally, in 1999, the National Committee of Linguistic Standards proposed a significant reform to de-Russify the language. However, it was never implemented.

Krytyka was one of several publications that decided to write and publish in a reformed orthography, contradicting the government’s official guidelines. They call their specific variation on this orthography “dyvnychivka” after Vadym Dyvnych, who has served as Krytyka’s copy editor since nearly the beginning.

The nature of “dyvnychivka” is complicated, covering issues like when to use the letters г (“h”) and ґ (“g”), as well as how to transliterate foreign names and how to spell words borrowed from Greek. However, in essence, it constitutes “a break from practices of violent Russification”, Dyvnych says.

Krytyka’s social engagement is not just academic. The journal has also helped delve into critically important yet challenging issues for Ukrainian society.

For example, Krytyka has published several volumes on the Holodomor, the 1932-33 Soviet man-made famine that killed over 4 million Ukrainians — a historical trauma that is important in Ukraine’s national narrative, but remains hotly debated abroad. In covering subjects like this, Grabowicz believes that Krytyka’s contribution may lie less with its specific publications than its approach. He credits the journal with creating a new standard for intellectual opinion writing and a community of writers dedicated to using that approach to advance democracy and political openness.

“We have managed to create a kind of consensus of liberal, pro-Western, pro-Democratic opinion implicitly focused on partnering with colleagues from neighboring countries and from the West”, Grabowicz says.

At times, Krytyka’s publications have even been prescient. While helping upload articles from past issues to the Krytyka website, Julia Bentia noticed that her colleagues had predicted many things — including Russia’s attitude toward Ukraine.

“No one had any illusions”, she says. “You can trace this through the texts”.

Looking To The Future

As Krytyka marks its 20th birthday, it is increasingly confronting the challenges of the 21st century. Surprisingly, few of those challenges are specific to Ukraine. Although the country has experienced revolution, war, and the start of a broad reform process since 2014, these events have not altered Krytyka’s core mission significantly, Grabowicz says. In many ways, that is because the journal was ahead of the intellectual and historical curve.

“After the Revolution of Dignity, after Euromaidan, after the flight of [ex-President Viktor] Yanukovych, many of the things that we had been arguing for are now part of the new national consensus”, he says.

The larger challenge is adapting to a changing economic and technological environment. Like virtually any specialized publication with an intellectual readership, Krytyka has always struggled with funding. The economic crisis that followed the Maidan revolution and the start of the war, has also been a blow. Still, the journal is chugging along.

A more delicate problem however may be in adapting to changing technology. Currently, Krytyka is published every other month — although it hopes to become a monthly journal again in the future. It has also recently changed its format, becoming a smaller publication. Bentia admits it can be challenging to adapt to a world in which social media is shortening attention spans and internet users expect free content.

“One of our problems is that, with the internet, people want to read shorter texts”, she says.

But these changes bring their own advantages. Krytyka first went online in 2007. It took a while for the site to develop, Grabowicz admits, but by 2014 or 2015, it had become “professional”. And unlike the print journal, Krytyka’s website is available in both Ukrainian and English.

Naturally, the Ukrainian site is more active. But the journal has a strong and ever-changing pool of authors and talented translators. It translates Ukrainian texts into English and foreign-language writing into Ukrainian, bringing together intellectual analysis of Ukraine from around the world, Bentia notes. It’s website is now more popular than the print edition, making Ukrainian intellectual thought available to a broader, more international audience.

Most importantly, Krytyka is not afraid of different views. Its journal and website cultivate the kind of environment it wants to see in Ukraine — intellectual openness, pluralism, and internationalism.

“Krytyka is a bridge between Ukraine and the world”, Bentia says.

Matthew Kupfer is Senior Editor at The Odessa Review.