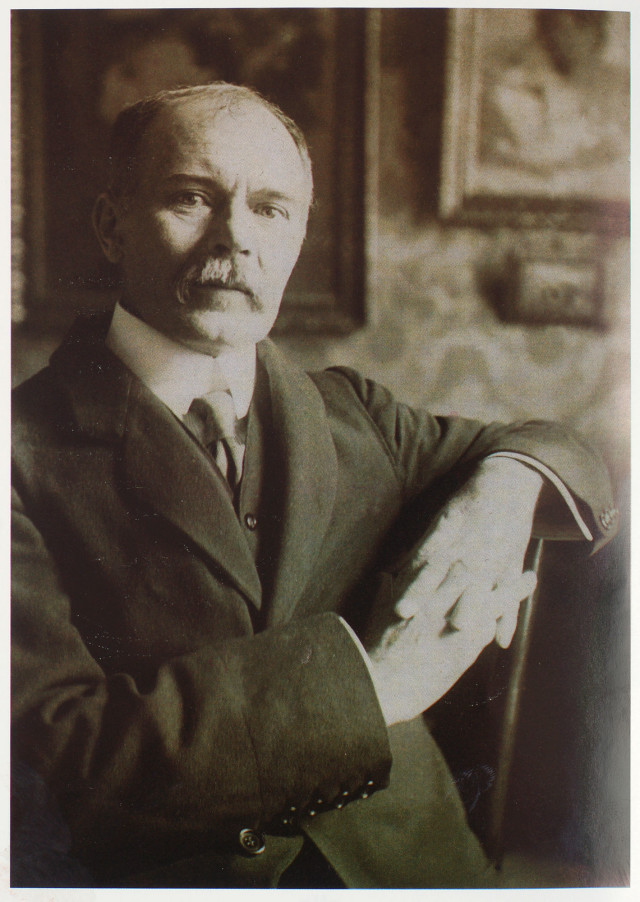

Amongst Odessa’s numerous artists, Pyotr Pavlovich Gansky remains relatively unknown. Despite the artist’s Odessa ties and his remarkable work, he has only recently received recognition in the city, as both a talented pre-Revolutionary painter and “the first Russian impressionist.”

In the Odessa Museum of Fine Arts, an exhibition took place featuring the work of the forgotten Odessan artist Pyotr Pavlovich Gansky, coinciding with his 150th birthday. The exhibition offered art enthusiasts much to reflect on, not least the fate of the creative heritage of Russian impressionism.

With his cantankerous spirit Gansky would likely have argued for the right of the creator to deliver their “pure” art directly to the audience, without any sort of mediative middleman or institution, though today we are more accustomed to the “withdrawal from context” approach. Yet without incorporating Gansky’s own story into our reflection on his surviving works, his paintings might be considered by the viewer to be no more than frivolous watercolor and pastel pieces — perhaps appealing, but fatally colored by the Odessan commercial artistic impulse: “come, don’t be stingy, buy a painting!” However, when considered alongside the artist’s biography and his sketches and drafts, these works acquire the features of artistic treasures.

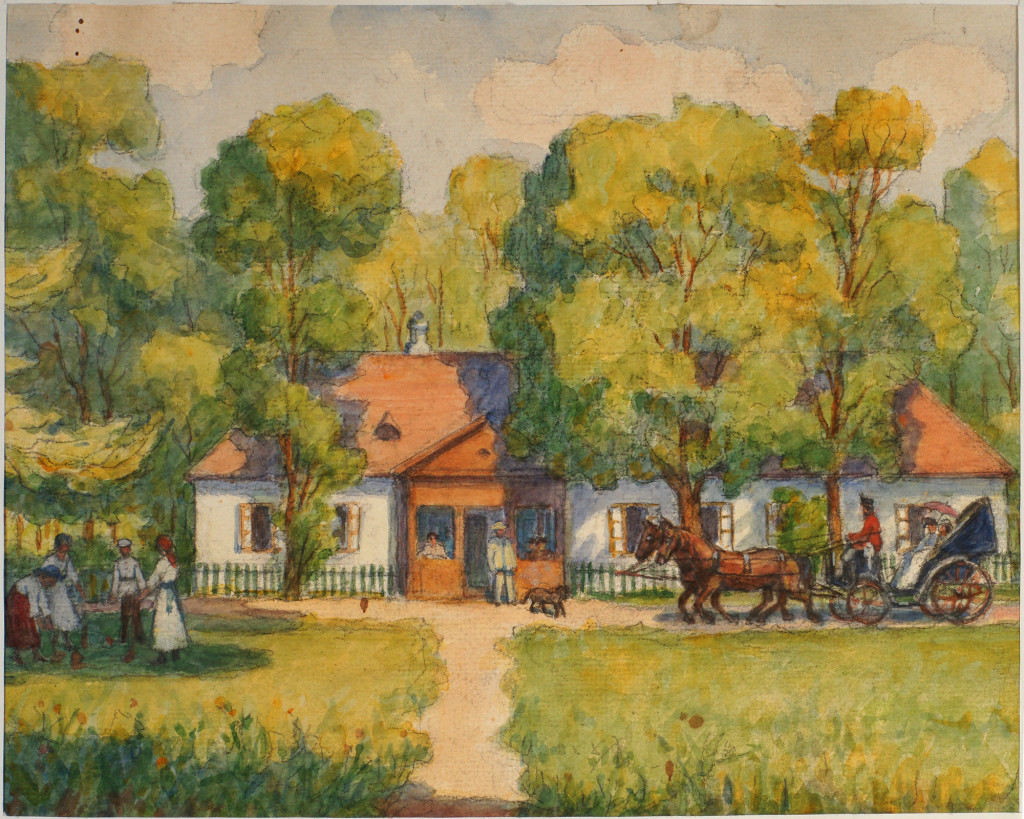

Gansky was born in 1867 on his’s family estate near the village of Nikolaevka in the Ananyevsky district. His parents, Pavel Petrovich and Elena Zimnitskaya moved the family moved to Odessa in 1870. Despite being the first-born son, stories and correspondence between family members suggest that he did not enjoy a good relationship with his parents.

This may explain Gansky’s unusual early education. We would expect that given Gansky’s status having been born to an Aristocratic familly, he would have been sent to the prestigious local Rishelyevskaya Gymnasium, his father’s alma mater, but he was instead sent to live with his relatives in Elisavetgrad, to study at the decidedly less glamorous school there.

It appears that it was in Elisavetgrad, Gansky’s creative journey began. After studying under the artist Pyotr Aleksandrovich Crestonostsev, Gansky travelled to St. Petersburg, where he volunteered at the St. Petersburg Academy of Art for four years. He continued his education in Paris, at the Jerome School of Fine Arts. After 1890, the artist would spend his winters in Paris, returning to Odessa in the summer. He already spoke with the authority of a master when he appeared at exhibitions of Odessan artists in the Parisian salon, and he would mingle with French creative society at it’s highest levels.

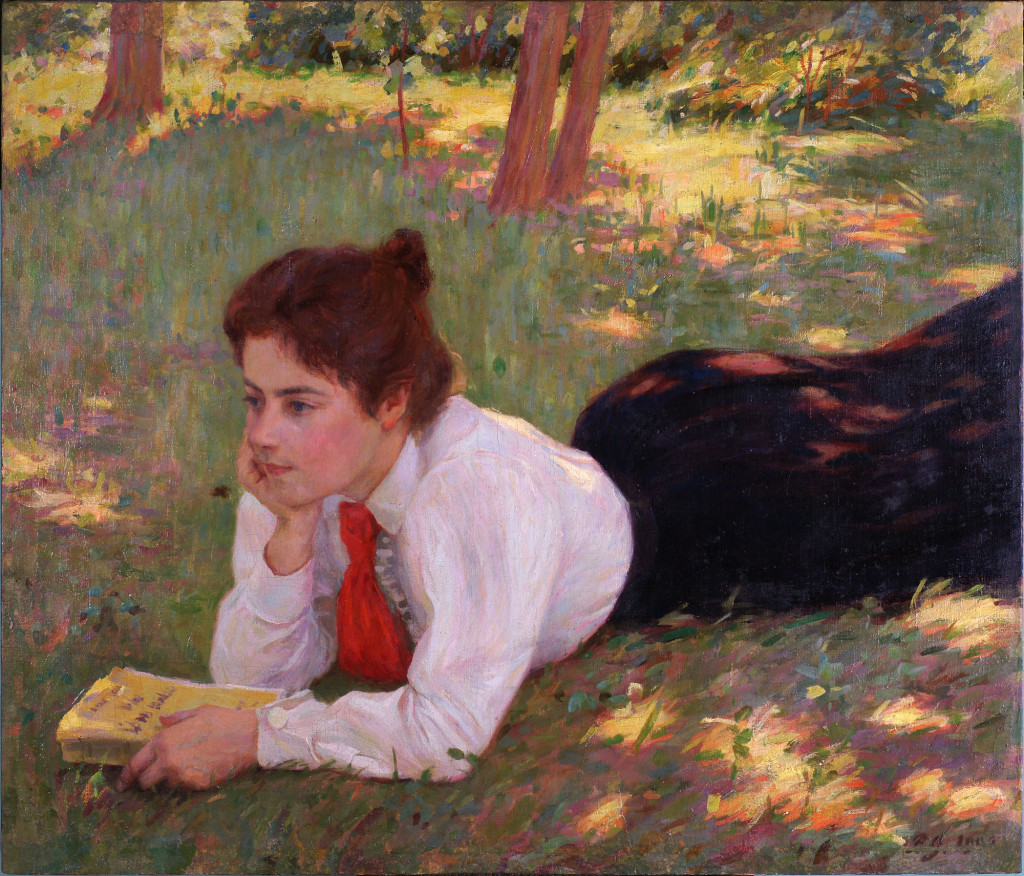

The portraits presented at the Salon exhibition featured personalities close to Gansky — his sister, his brother, his niece. The image of the carefree girl which appears on the poster for the exhibition is a portrait of Sophia Bystritskaya (née Ganskaya), Gansky’s sister. Married to an Imperial officer, she found herself unable to return to her homeland after the revolution, and remained in exile in Paris. From 1920, after Gansky himself emigrated, until the end of his life, Sophia and her family were his closest friends. Sophia’s daughter, Kira, preserved an archive of her uncle’s work until the 1990s, when they would appear in Tallinn. Eventually, they made their way home to Odessa.

Another portrait, darkened with age, depicts the acclaimed astrophysicist Alexei Pavlovich Gansky, the artist’s brother and one of the founders of the Simeiz department of the Pulkovo Observatory. He would become known for his work in Odessa, St. Petersburg, Paris and Potsdam. He rubbed shoulders with the most well-known scientists of his day, from Pierre Janssen and Maurice Levy to Herman Karl Vogel, and traveled as far afield as Novaya Zemlya in the Arctic Circle, and to the top of Mont Blanc, which he scaled on nine separate occasions. Gansky joined his brother on an expedition to Spain in 1905, and helped to illustrate a solar eclipse. Gansky was also commissioned to paint his brother and his colleagues, including Janssen, whose portrait hangs at the Pulkovo Observatory along with that of Alexei.

As a wealthy landowner, Gansky was arrested by Bolshevik forces and sentenced to death in 1919. After he had spent several months awaiting execution in prison, he was freed by the volunteer army that stormed the city. The details of his arrest are confirmed in the diary of Vera Muromtseva-Bunina, as well as in the records of arrests and interrogations relating to the Bolshevik case against the “Russian Peoples’-State Union,” of which Gansky was a member. He was the only member of the organization to avoid execution. His miraculous survival appears to be the result of a ransom paid by none other than Ivan Bunin himself. In an entry in his wife’s diary from 1919, she notes that “the liberation of the artist Gansky cost seventy thousand rubles. Bargained for a long time. He was arrested, accused of being a landowner and a rabid anti-Semite. He sat in the jail at Marazlievskaya and painted portraits of his captors.”

Ivan Bunin himself never mentioned Gansky in his diaries, but he appears even before 1919 in Vera’s diary. In 1918, she writes about having tea with the artist: “Yesterday evening we had tea with the Nedzelskys. They were joined by the artist Gansky, the first Russian impressionist […] between Gansky and Talinov there was a very tense conversation about the Jews. Gansky is an outspoken, almost maniacal anti-Semite.” Gainsay was very often an unattractive character in his private relations.

On a Sunday in 1994, more than 50 years after Gansky’s death, two women appeared at the Odessa Museum of Fine Arts. With them, they carried a reticule containing a stack of sketches and family photos. They were sure that the museum would be at least vaguely familiar with the name of Pyotr Pavlovich Gansky. As they displayed the contents of the reticule to the museum’s staff, the creation of the largest museum collection of the “first Russian impressionist” was set in motion. Ten years later, these two women — Tatyana Kashneva and Elena Posdnyakova — plan to donate dozens of Gansky’s works to the museum, making for a total of 84 of Gansky’s pieces in the museum’s collection. More than 60 of these will be displayed at another exhibition which will take place later in 2017.

The exhibition of Gansky’s work is beautifully and fittingly complimented by the neighboring exhibition of the beloved avant-garde painter Tatiana Yablonskaya (also in celebration of her 100th birthday). The well-known Ukrainian and Soviet avant-garde artist has more in common with Gansky than might be expected, as evidenced by details in her biography which emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Impressionism played an important role in her work, as noted by both scholars and the artist herself. Gansky’s pre-Soviet art — which is also characteristically Ukrainian, despite the artist’s self-declared “Russian-ness” — is clearly evoked in Yablonskaya’s Soviet-era works.

Gansky was many things — an artist and a philosopher, a man of both talent and violent prejudice. Ordained as a Jesuit priest in 1928, he sought to bridge the gap between Orthodoxy and Catholicism. With his longtime friend, the painter and explorer Nicholas Roerich, he endorsed the Roerich Pact and signed it before Pope Pius XI.

Before the Revolution, the artist signed his work as Pierre Gansky, an affectation displaying his European education and socialization. In the 1920s, his signatures disappeared from his work, and in the press he was referred to as Pierre Hanski, his Russian and Ukrainian background further receding into obscurity. Gansky’s work was similarly lost to history, but today Odessa is fortunate enough to finally reclaim his art and legacy, three quarters of a century later.