A profile of the an artist, director, promoter, set designer who who is arguably the most interesting man now working in Ukrainian theater as he prepares fore the premiere of his opera “Babylon,” which is set to open this August.

I have come across very few arts visionaries who seem to alter the energy of those around them, and who, even with their outlandish ideas, change reality by the force of their imagination. What is now real was once imagined, in the words of William Blake. Some people I would put in this precious category are Malcolm McLaren, Joseph Beuys and Fela Kuti. I would not hesitate for a second however to add to that list Ukraine’s Vlad Troitsky as an important cultural catalyst for all of world culture full stop.

Troitsky has been the director of Kyiv’s storied Gogolfest every year since its inception, showcasing hundreds of Ukrainian artists of all stripes. This year’s fest motto is “Don’t wait – do something”. He was also instrumental in turning the Arsenale in Kiev into the modern, dynamic art centre it is today. He is always on the go, but believes that one of the secrets of happiness (“and I am a very happy man” he says) is to live in the present rather than the past or future. He has kept off Facebook and limits the negative feelings he gets from overexposure to media, but knows exactly what is going on politically.

Troitsky holds a seductive and positive line on Ukraine’s cultural situation. For him, Western Europe is “tired and cynical”, a place where everyone feels things are always getting worse — but that is not so in Ukraine, where things are on the up. Russia is an authoritarian, backward looking place that wants to send women back to the kitchen — Ukraine is a dynamic cultural place that holds more possibilities than ever. It is, after all, the most fertile area of Europe, the place with the richest, darkest soil. A feminine country — with a strength that implies that there is “a lot of shit”, corruption, war and all the rest, but “step by step”, it steadily improves. “It’s not so cool for a bureaucrat to be driving a flashy car that he has afforded through taking bribes now”, he asserts.

Troitsky isn’t a head-in-the-clouds sort of guy, but he does have a bracing grip on the big picture. His new opera “Babylon,” which will open this August, is his reaction to the rise of populist nativists embodied by Brexit, Trump and Le Pen. Countries and cultures don’t understand each other, and don’t want to anymore. It is typical for Troitsky to draw direct parallels between personal and state relationships. “The EU was a romantic idea,” he says “but like all romances there is the romantic phase and then…” relationship experts argue a power struggle phase and a “Dead Zone,” when you don’t know who is sitting opposite you at breakfast. Troitsky believes “Ukraine is at a romantic phase, which is why it is so powerful.”

His ideas would be interesting from a theoretical point of view, but what gives Troitsky his power is that he turns many of them into reality. Whoever it was that said magic is the correct combination of will power and imagination could have been thinking of Troitsky. There was a feeling that Ukraine needed more contemporary music — Troitsky essentially dreamed up and put together the wildly popular neo-folk Dakha Brakha (in a not dissimilar fashion to the way that McLaren put together the Sex Pistols). Since then, he has been art director to Dakha Brakha and the all female “freak cabaret” group Dakh Daughters.

Full disclosure if it can be called that: the first UK gig of Dakha Brakha, ten years ago, actually took place in my front room in Hackney, East London. It was attended by ten people. Now the ladies play to adoring crowds of thousands at the WOMAD and Glastonbury Festival, playing original and soulful music that is rooted not only in Ukrainian, but also in global culture. Likewise for the Dakh Daughters, whose video of them playing at the Euromaidan is a great introduction to their work. Now they too are touring internationally to critical acclaim.

Troitsky mentions that when Dakh Daughters played the Vienna Festival recently, a feminist gave them two reactions – she got a wonderful sense of freedom from the band, but was suspicious of Troitsky as a sort of patriarch daddy figure. The band replied that if she got this sense of freedom – why try and impose her ideas of feminism on them? It’s true that in this band there is a singer who is a married mother, and another who tells everyone she had an affair with an artist and his wife at the same time. That is a sort of freedom, perhaps. Troitsky might also say that in Western Europe there is a feeling that the sexual electricity between men and women is not what it once was — a diminution of the life force. For him, the “intellectual, sexual” Dakh Daughters on stage are the greatest ambassadors of the new Ukraine. Certainly, the two bands have inspired plenty of other groups to form, and if a Ukrainian musical renaissance is no longer a ridiculous or wishful idea, he is as much responsible for it as anyone.

I first met Troitsky a decade ago, when he was about to bring a version of Macbeth to London’s Barbican Theatre. I was immediately struck by that inimitable sense of a positive vision allied with a steely will power. Soon I was staying at his place in Kyiv, and every morning, even if the river Dnieper was frozen over, he would go swimming. He talked of going to a shamanic retreat in Siberia where you would be buried in an ice hole for days.

In fact, Troitsky was born in Siberia, but has lived in Kyiv for the last 35 years. At the collapse of the Soviet Empire, Troitsky built up a business which included shops on the main Khreshchatyk boulevard in Kyiv. Being an avant-garde theatre enthusiast, he bought a building in downtown Kiev twenty years ago and called it the Dakh Centre of Contemporary Theatre Arts. He set up a school for modern theatre, enrolled himself in it and invited directors that he admired, such as Igor Lysov, to come and lecture. In some ways his work aims to revive the theater milieu of the Soviet times, when Eastern European directors such as Tadeusz Kantor and Jerzy Grotowski produced idiosyncratic, physical theater that was among the most innovative in the world.

To return to my first night in Kyiv – we ended up at a fashionable restaurant which usually has a stylish, minimal décor. Except this time, the Dakh Centre for Contemporary Arts theater company covered the place with straw. There were live chickens everywhere, several actors were dressed as Ukrainian peasants, and a gang of musicians with drums and violins played in a music style that they described to me as “ethno-chaos”. Next, a dozen stunning girls arrived, dressed in bridal white. We went outside to an old amphitheater, where bonfires were lit and the brides began to rhythmically strike large sheets of metal with hammers. The movers and shakers of Kyiv’s fashion, media and business worlds were there in force and the event was judged to be a great success. The restaurant got lots of publicity and the theater company was paid enough to keep them going for a few more weeks. Which is not beside the point, as it survives by performing these kinds of stunts. There was the opening of a nightclub called Guerrilla, where the dress code was Soviet military chic (though the notion of Soviet chic has declined understandably in the last few years).

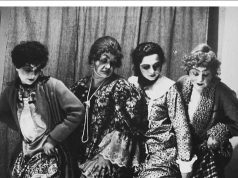

The company’s version of Macbeth loosely followed Shakespeare’s story, though with fairly little dialogue. Sometimes there were four witches and sometimes two — these were beautiful young sirens rather than old crones. Troitsky focused on the essential, archetypal elements of the play, and created a highly ritualistic piece using dance, masks and music to tell the story in an almost trance-like atmosphere. The mesmerizing music reflected his interest in the vocal traditional folk music of the Carpathian Mountains. It was also the first time that I heard the captivating music of Dakha Brakha. The play premièred in its original form a week before the Orange Revolution in November 2004, and the Macbeth tale of politics taken to extremes had obvious and striking contemporary resonance. Troitsky and his theater company were activists then, too, behind numerous “happenings.” One of these was the act of delivering thousands of old shoes to the Russian embassy and keeping up the morale of protesters by performing for them. There have been many other theater productions, such as a take on the Biblical story of Job, that emerged in the last year. Troitsky talks intensely of his belief in a theater of “intellectual clowning, mystery, ritual and neo – baroque aesthetics”, theater as a vehicle for spiritual self-realization.

His health has suffered in the last few years and he said he had been on a two week Ayurvedic retreat in Kerala India. But “fine words butter no parsnips”, and Troistky is a man of action and not merely of ideas, which is why he is to be treasured. In a TED talk he spoke of his belief that the old days of status and money politics were coming to an end. There would be a new politics of altruism where people got the most pleasure and status from giving things – attention, talent, money. All you would need to do is find people to accept your gifts. Crazily optimistic — especially in the new old Ukraine – but if anyone is likely to bring such a vision down to earth, it could only be Troitsky.

Peter Culshaw is a composer and writer who has been everywhere and knows everyone. He once got very drunk with Fidel Castro. He is the author of ‘Clandestino: In Search of Manu Chao’.