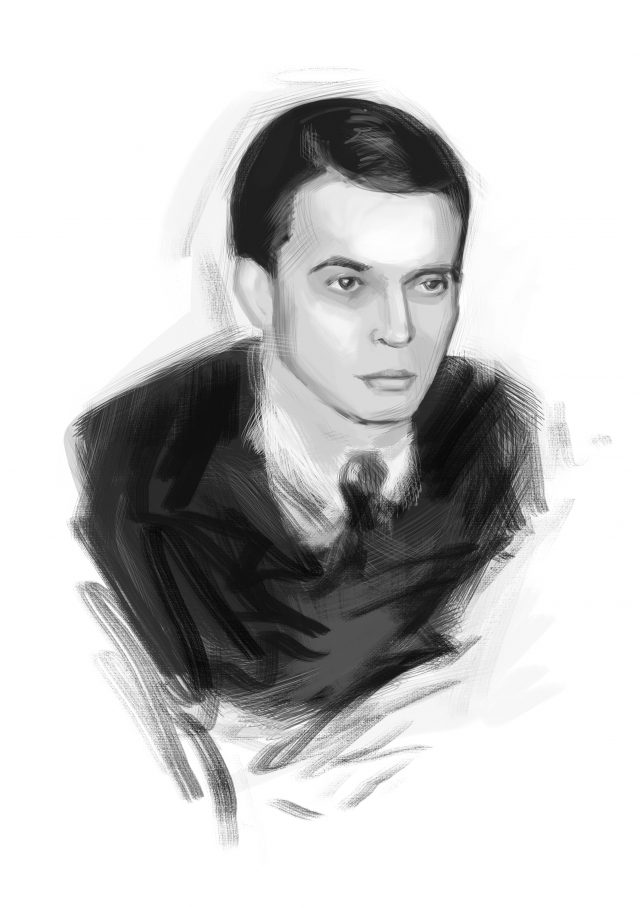

The poet Pericles Stavrov is known to lovers of literature as one of the great poets of the 20th century. This article is based on selections from Yevgeniy Demenok’s book on Odessa literary culture.

For a large European city, Odessa is young. But it is rich in influence. At just 220 years old, the “Southern Palmyra” is traditionally called the ancestor of two modern states: Israel and the Greek Republic. It was from Odessa that the youthful “Hovevei Zion” (“Lovers of Zion”) movement, founded by Leon Pinsker and with Moses Lilienblum, went to Palestine to reestablish the Jewish state. And it was in Odessa in 1814 that local activists founded the secret society “Filiki Eteria,” a national-patriotic organization whose activities led to the overthrow of Ottoman rule and the revival of Greek independence.

But Odessa’s Greek history predates the city itself. In the VI century BCE, there were two Greek settlements and harbors where modern Odessa now stands. Relics of antiquity — amphoras, earthenware, anchors — continue to be found in the city center today. And the surrounding region was sprinkled with Greek colonies: Tyras, Nikoniy, Isakion, even the powerful Greek polis of Olbia.

In its first city plan from 1794, Odessa is divided into two sections, military and Greek. And the first census of the city’s population, taken in 1795, shows that 224 of Odessa’s 2,349 residents were Greek.

As it grew, Odessa quickly became a reliable harbor for the Greeks. After the Turks brutally killed the Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory V, in 1821, he was buried in Odessa’s Holy Trinity (Greek) Church. By the beginning of the 19th century, Odessa had become one of the largest cultural centers of the Greek world. Greek writers like Yannis Psycharis and Dimitrius Vikelas traced their roots to Odessa. The city boasted a Greek theater and a Greek school. From 1878 to 1895, the city even had a Greek mayor, Grigory Marazli. The writer Psycharis even gave an enormous boost to the burgeoning literary movement in Greece with “My Journey,” a book promoting vernacular Greek.

But perhaps one Odessa Greek writer crossed cultural boundaries more than any other: the poet Pericles Stavrov. As a new literary style flourished in early 20th century Odessa, Stavrov emerged among acclaimed writers like Isaac Babel, Eduard Bagritsky, Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov.

However, in the Soviet period, Stavrov’s name was nearly forgotten. This is not surprising: he was an émigré. After experiencing the horrors of the civil war, the endless regime changes, war, communism, and poverty, Stavrov used his Greek citizenship to escape Soviet Russia in 1926.

The poet Yuri Terapiano, who knew Stavrov well in Paris, wrote in his memoirs:

“Stravrov did not want to follow the example of many of his colleagues, to remain a Soviet writer, and so he went abroad — ‘to his fatherland, to Greece.’ But, as he himself later said, ‘in his country’…Stravrov and his wife were always considered ‘Russians,’ and they themselves felt good only among Russian émigrés.”

Like thousands of so-called “Russian foreigners” from the Empire’s south — born, raised, and educated in Russia — “Stavrov remained faithful to the Russian cultural tradition to the very end,” Terapiano wrote, “living abroad for a long time, [but] thinking and writing in Russian.”

Pericles Stavrovich Stavropoulos was born in Odessa in 1895. In 1918, on the eve of the Bolsheviks’ arrival, he graduated from the law faculty of Novorossiysk University. A year before graduating, Stavropoulos began writing poetry, much of which was published in “Bomba,” an Odessa magazine. His early works strongly imitated the experimental verses of Russian futurist poet Vladmir Mayakovsky.

For example, in one of his earliest poems, “In Cinematography,” the young Pericles Stavropoulos writes:

“Вы! В грязной панамке!

Серый слизняк,

Сюсюкающий над зализанной самкой,

Подтянитесь и сядьте ровнее!

Сегодня вы — граф де Реньяк,

Приехавший из Новой Гвинеи,

Чтобы похитить два миллиона

из Международного банка.

А ваша соседка с изжёванным лицом,

Дегенератка со склонностью к истерике,

Уезжает с очаровательным подлецом

В какую-нибудь блистательную

Америку!”

“You! In the dirty panama hat!

A grey slug,

lisping over a female with slicked down hair,

Pull yourself together and sit up straight!

Today, you are the Count of Regina,

Arrived from New Guinea,

To steal two million

from the International Bank.

And your neighbor with the chewed up face,

A degenerate inclined to hysteria,

Is leaving with a charming scoundrel

For some kind of shining America.”

As the years passed, Pericles Stavropoulos changed his style. He was enthralled with the works of Fyodor Tyutchev and Innokenty Annensky. In Paris, where the poet moved from Athens (via Bulgaria and Yugoslavia), he published two collections of poems under the pseudonym Stavrov: “Without Consequences” (1933) and “Night” (1937).

After the publication of the first collection, Stavrov entered the circle of the Parisian “younger literary generation,” and became a participant in émigré writer Dmitri Merezhkovsky’s “Green Lamp” literary society. The Russian émigré poet Georgy Adamovich wrote that Stavrov’s poems “reach the mind and heart, as something creatively tense and unquestionable.”

Take, for example, his poem “This White Distance:”

“Всё прошло, развалилось, опало

В светлой сырости осени злой,

И взлетает последняя жалость

Легче крыльев за бедной спиной.”

“Everything has passed, collapsed, fallen

In the light dampness of cruel autumn,

And the last pity takes flight

Lighter than wings on a suffering back.”

In the 1930’s, Stavrov and the French writer René Blech opened a small bookshop, “Un- der The Lamp,” in the heart of Paris’s Latin Quarter. The shop became a daily gathering place for Russian and French writers. The Soviet satirists Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, both Odessans, even visited their friend Stavrov there in 1934. Working with Peruvian writer Victor Llona, Stavrov had just translated the duo’s novels into French. During the visit, he presented Ilf a copy of his first collection of poems.

Almost seventy years later, in 2003, that book became the genesis for “On the Beat of a Wing,” the only collection of Stavrov’s poetry and prose to ever be published in Odessa. Ilya Ilf ’s daughter Alexandra had shown the collection to Odessa journalist Yevgeny Golubovsky. He had also found a number of early poems by Stavrov (still Stavropoulos at the time) in Odessa newspapers and asked the the Paris-based poet and journalist Vitaly Amursky to seek out a second collection of Stavrov’s writing.

In 1939, on the eve of World War II, Pericles Stavrov was elected chairman of the Association of Russian Writers and Poets in France. Although the Nazis would eventually close all Russian public organizations in France, the Union continued to operate covertly. Stavrov’s apartment became a secret meeting place for writers.

During the Nazi occupation, Stavrov began to write short stories, which he published in the “New Russian Word” journal and other publications from 1945 onward. He also translated his own stories, as well as the works of writer Ivan Bunin, into French and published them in French journals. Bunin was an old aquantance of Stavrov’s — they had met in Odessa in 1918.

In 1945, after the liberation of France, Stavrov and poet Sergei Makovsky began publishing a literary magazine called “Meetings.” Sadly, it didn’t last long due to financial troubles. In his last years, Stavrov also wrote articles on art and was preparing to publish a book of his stories. Unfortunately, it never saw the light of day. Pericles Stavrovich Stavrov died in 1955. Until the last months of his life, he played an active role in the literary life of “Russian” Paris.

Although Stavrov never returned to Odessa, his last years brought one final Odessa-re- lated event: In the late 1940’s and ‘50s, Stavrov wrote and published a series of essays about his Odessan and Parisian friends and acquaintances — people such as the writers Yuri Olesha and Eduard Bagritsky, the religious philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev, and Russian poet and French Resistance member Boris Vildé.

In the anthology “Ten Centuries of Russian Poetry,” the late Yevgeny Yevtushenko writes of Stavrov:

“He was tacitly considered a third-rate poet. Spoiled by the sheer variety of talents in [Russian] literary emigration, readers and critics were inattentive to his work. Meanwhile, being a stable third-rate [writer] in Russian poetry is a very, very honorable rank. I myself unfairly excluded his poems in ‘Verses of the Century.’”

Pericles Stavrov is one of those poets who does not deserve to be forgotten. Dear reader: reread his poems and remember the Odessan’s rare talent:

“Утро рассветною пылью туманится

В розовом облаке перистых чаяний,

День начинают святые и пьяницы

Для ожиданий, намеков, раскаяний.

…Как на беду ничего не случается.

Жить очень хочется.

Жизнь продолжается.”

“The morning is fogged with dawn’s dust

In pink clouds of plumy hope,

Saints and drunkards start their day

For anticipation, intimation, repentance.

…Unfortunately, nothing is happening

I so want to live. Life goes on.”

Yevgeniy Demenok is a writer, journalist, and cultural historian who has authored five books. He is a winner of the Paustovsky’s Municipal Literary Prize for his 2014 book ‘New, on the Burliuks.’ He is a founding organizer of Odessa Intelligentsia Forum and a member of the Presidential Council of the Worldwide Club of Odessans.