One of the more unusual exhibitions of last year’s art world calendar took place at the Yeshiva University Museum in New York City: “Odessa: Babel, Ladyzhensky, and the Soul of a City.”

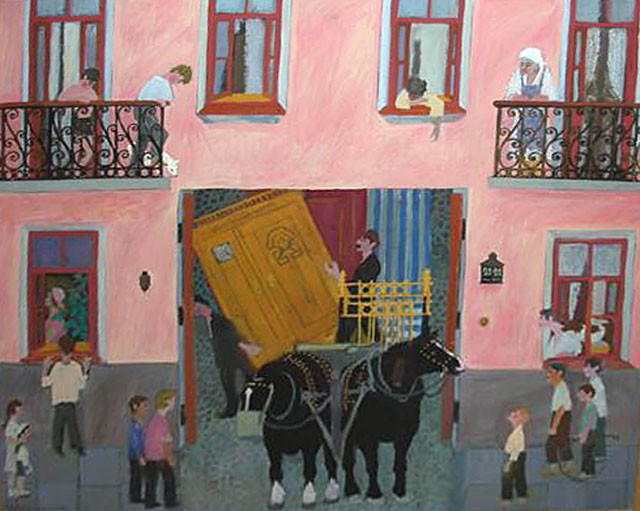

The exhibition runs March 27, 2016 to January 15, 2017 and constitutes an approach through the eyes of two natives who depicted the city with remarkable vividness. If Isaac Babel is one of the great names in Russian literature and a consummate master of the short story, the second name is much less familiar. Yefim Ladyzhensky, a generation younger than Babel, was an artist who while earning a living in Moscow as a painter of theatrical scenery, privately painted scenes of his childhood in Odessa, depicted — as David K. Shipler wrote in the New York Times in 1983 — as “a festive, bustling city of gaily painted trams, sailors and holiday crowds in white, of flower vendors and brass bands, amusement parks and fish stalls, horse-drawn carriages, communal baths, cafes and fashionable people at the opera. There were also bar mitzvahs, marriage feasts, synagogue scenes and other Jewish themes the Soviet authorities didn’t allow him to exhibit.” In 1978 Ladyzhensky emigrated to Israel, where he hoped that his depictions of Jewish life would find a receptive public. But the young nation was not so interested in a nostalgic look back at the world of yesterday, and the painter was unprepared for life as an artist under capitalism. “He was unable to adjust to the free market in art, refusing to sell paintings or to let gallery owners bargain with customers over prices,” according to Shipler. “He felt it was demeaning.” In 1982 the artist hanged himself in his studio. Interest in the work of Ladyzhensky is currently experiencing a renaissance.

Ladyzhensky’s work came to me as a complete surprise. It seemed to present a complete and self-contained world in which memory has been reordered by imagination to distill the truth of a child’s fascination with the color and variety of the not-quite-comprehensible world around him. Along with the tempera paintings based on his own recollections, the exhibition also included drawings illustrating Babel’s “Odessa Stories.” It struck me that it would be fascinating to see the reaction to Ladyzhensky of a contemporary painter whose work has also flirted, at times, with illustration — which has long been a taboo for serious artists — so I asked the Russian-American painter Sanya Kantarovsky to discuss Ladyzhensky’s work with me. Born in Moscow, Kantarovsky grew up in Rhode Island and now lives and works in Brooklyn. Figures and actions in Kantarovsky’s paintings are metaphors for social or psychological situations — they suggest stories rather than limn them — but for his 2015 exhibition “Apricot Juice” at Studio Voltaire in London, he drew more specific inspiration from Babel’s close contemporary Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. As I suspected, Sanya’s response was illuminating.

— Barry Schwabsky

Barry Schwabsky (BS): So what was your take on the exhibition?

Sanya Kantarovsky (SK): I was impressed by the show. Ladyzhensky really captured a particular Benya Krik ethos in the pictures, and although they’re quite provincial and Jewey in that Chagallesque way, there is something quite complicated about most of them, both formally and in terms of the affect they’re laden with. It was especially sad thinking about the fate that befell on this Odessa. The Odessa massacre was the single largest mass killing by the Nazis, and before the war the Jewish population comprised nearly a third of the city.

BS: You won’t be surprised to hear that I saw the show in a different way. Putting aside for the moment the works on paper that were literally illustrations of Babel and speaking specifically of Ladyzhensky’s paintings, I was surprised by how un-literary they are, first of all, and secondly how far they are from the fantastical folk surrealism of someone like Chagall. What struck me first of all was the firm but not rigid geometrical structure that Ladyzhensky gave to most of his paintings. There’s a lot of repetition of similar small units within any given painting but never in the spirit of horror vacui that we find in naïve or outsider art. It’s more of a rhythmic structure with variable accents. Although the way he puts paint down is totally different — as would have to be the case given that Ladyzhensky used tempera rather than oil or acrylic — something about the way Ladyzhensky depicts the Odessa streetscape put me in mind of Martin Wong’s depictions of New York’s East Village in the 1980s. Spatially, Ladyzhensky’s compositions are more complicated than Wong’s, but I feel a connection. Maybe it does have something to do with articulating a minority viewpoint on one’s surroundings.

SK: I can see why you thought of Martin Wong. I think at first glance, the first similarity that jumps out at me is both described urban architecture with a particular attention to its skin — in this case bricks. In both there is a kind of democratic depth of field — we see every brick of the wall painted with the same attention as a heads in a crowd, or watermelons in a truck. I also agree with you that in Ladyzhensky’s paintings, (as well as in Wong’s) this meticulous, almost handicraft is less related to values of folk and “outsider” art than to a kind of reverie of looking and describing one’s city as a dense entirety. I remember in “LA Plays Itself,” LA’s often short depth of field in films was compared to New York’s immediately recognizable corners. LA’s anonymity on camera allowed it become many other cities. New York betrayed itself almost immediately — it was always New York. It seems to me, that perhaps to both Ladyzhensky and Wong, this attachment to detail had to do with a desire to describe their home cities in their dense entirety, ensuring them against loosing their specificity and becoming backgrounds. I’m not quite sure how you see this relating specifically to minority viewpoints — I also begin to think of Weegee’s photographs and Jacques Tati’s films. As far as the Chagall comparison, Ladyzhensky’s pictures are certainly more blunt and flatfooted — no flying people or rose colored sheep. However, they do betray a kind of archetypal Jewish tenderness and naivete which marked Chagall’s oeuvre. Its the one characteristic of the paintings that actually felt out of sync with Babel, whose stories operated through a darker, drier sort of humor.

BS: Yes — Ladyzhensky is much more indulgent toward his characters than Babel ever is. At the same time, though, he portrays people at a much greater distance. There is typically a multitude of little figures scattered around the rectangle — they never come close to filling the space, which is dominated instead by the setting: buildings and streets. There is no close-up view of the face. Each figure has its own idiosyncratic characteristics, but they are not really important. The figures are fungible. Whereas Babel, I think, is a narrator in the mold of the Old Testament, in whose words all the important meaning resides precisely in that which “we are not told,” to borrow Erich Auerbach’s words from his famous analysis of the Biblical story of Abraham. “Where is he?” asks Auerbach of Abraham, and goes on: “We do not know. He says, indeed: Here I am — but the Hebrew word means only something like ‘behold me,’ and in any case is not meant to indicate the actual place where Abraham is, but a moral position in respect to God, who has called to him—Here am I awaiting thy command. Where he is actually, whether in Beersheba or elsewhere, whether indoors or in the open air, is not stated; it does not interest the narrator, the reader is not informed; and what Abraham was doing when God called to him is left in the same obscurity.” Although Babel sets his stories in Odessa, he never describes the city. There is no loving graphic detail. It is the blank stage across which his larger-than-life Jewish gangsters stride like giants — never like the little people of Ladyzhensky — and the author allows (again quoting Auerbach on Genesis) “the externalization of only so much of the phenomena as is necessary for the purpose of the narrative, all else left in obscurity; the decisive points of the narrative alone are emphasized, what lies between is nonexistent; time and place are undefined and call for interpretation; thoughts and feeling remain unexpressed, are only suggested by the silence and the fragmentary speeches; the whole, permeated with the most unrelieved suspense and directed toward a single goal (and to that extent far more of a unity), remains mysterious and ‘fraught with background.’” The figures in Ladyzhensky’s paintings may be busy, but their activity has nothing of this depth — though it certainly has its own very different kind of charm and poignancy.

SK: Hmm. I wonder how much of this emphasis on setting vs. narrative has to do simply with the differences between a literary narrative and a visual one? It’s true that Babel focuses less on describing Odessa itself, but I think that the narratives and the characters that drive them, such as Benya Krik, are very specific Odessite types, a feature that was certainly recognizable to Babel’s audience. But it’s true that in Ladyzhensky’s pictures the city becomes an actual protagonist — and I think these repeating rectangles and shapes, which continuously serve as margins and containers for the tiny figures, assume more of an active role than that of a simple backdrop. I’m reminded of the way that the conquistadores appeared in Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God — minuscule and reckoning with the vast Peruvian Andes around them. The landscape became as important, if not more so, than the figures it contained. A similar thing seems to happen in Ladyzhensky’s paintings. As far as all of the figures being fungible — I’m also not so sure. In a weird way, I think they’re almost like the micro-narratives in the Where’s Waldo books. If you look closely enough you’re rewarded with mini-stories that veer away from the generic crowd towards the specific individuals. And what about the surface? I was struck with the consistent ultra-flatness of it. I guess that this is typical of tempera, but in these paintings, the powderiness felt very important and deliberate. It’s as though Ladyzhensky wanted to somehow de-classify his paintings, and make them feel more like pictures. There isn’t much to grab on to as far as surface tensions, everything feels more or less the same. This decision seems to take on a different form with the ballpoint pen drawings, which also feel deliberately fuzzy. I’m reminded of Balthus’s casein paintings, which had this extremely strange and uniform bumpiness, that also made them feel somehow less like paintings, and more like flat made things.

BS: I see what you mean about the paintings’ flatness. But I’d say it makes them feel more like signs than like pictures — I guess the word “pictures” to me suggests something with more space, as for instance in classical representation. There are at least two kinds of flatness in painting: There’s the modernist flatness that comes after the big history of European pictorial space from the Renaissance through the nineteenth century, and whose impact comes in part from the viewer’s understanding that the artist is deliberately and for sophisticated reasons collapsing all that space into an implacable plane. Then there’s the flatness of folk art. This represents a different path of development, one that skips the Renaissance discoveries of perspective, sfumato, and so on, altogether. From the viewpoint of technique, it is “innocent.” Of course, all the modernists were fascinated by folk art: in Russia, they looked at lubki; in New York, the Museum of Modern Art showed Grandma Moses. But the difference between modernist flatness and folk flatness is usually patent. Part of the fascination of Ladyzhensky’s paintings for me is that they are situated at a place where I can’t decide whether I think that he is a sophisticate who’s adapted the visual idiom of folk art or someone who essentially remained in spirit a folk artist despite having evidently taken on board something of modernism. Florine Stettheimer is maybe a little like that, but we’ve had enough time an experience with her work to sort out the real sophistication from the apparent naivete. Maybe in part because Ladyzhensky is new to me, I find this harder to parse in his case. If I knew more about his biography, and about the specific artistic context in which he was working — which is clearly tangential to anything that emerges from the standard histories in which Malevich, Rodchenko, Tatlin, and so on are the suppressed protagonists of Soviet modernism — I’d be less mystified. But I suspect I’d still be entranced by Ladyzhensky’s unique way of seeing things.

Barry Schwabsky is an art critic for The Nation and co-editor of international reviews for Artforum. His most recent books are “The Perpetual Guest: Art in the Unfinished Present” and a collection of poems, “Trembling Hand Equilibrium.”

Sanya Kantarovsky is a Moscow-born artist who lives in Brooklyn. Upcoming projects include a group exhibition at the Jewish museum in New York and a solo exhibition at the Fondazione Sandretto Rebaundengo in Turin.