This rendition of a classic modernist poem was translated by Boris Dralyuk, the Executive Editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Read our long interview with him here.

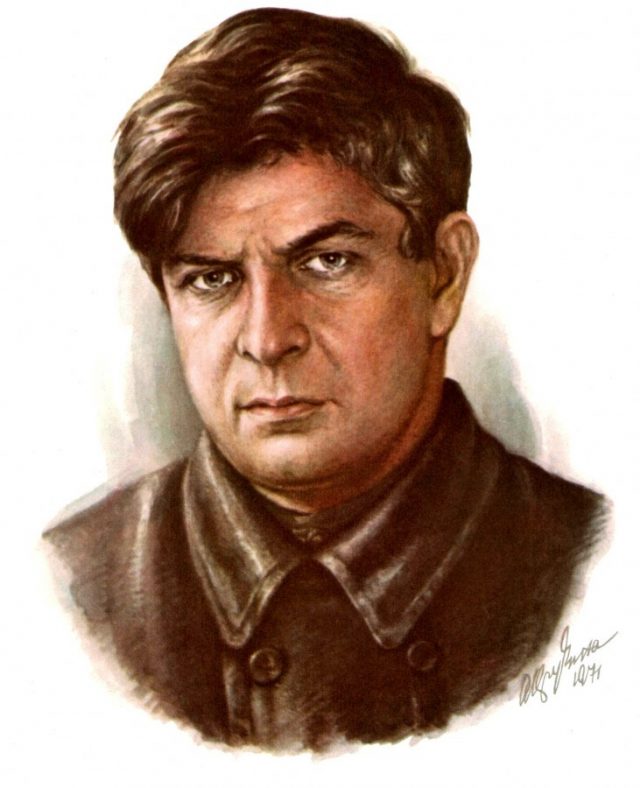

In the Soviet era, Eduard Bagritsky’s name was as familiar to Odessans as that of Isaac Babel — and it may still be. But unlike Babel’s, the name was a nom de plume, derived from the Russian word “bagrianyi”: scarlet, the color of blood. The poet was born Eduard Dziubin, to a secular Jewish family in Odessa in 1895. He began writing verse at an early age. Some of these youthful efforts appeared in a little anthology in 1915, under another (female) pseudonym: Nina Voskresenskaya. The anthology featured mostly Odessan poets who had fallen under the influence of the Russian Futurist; it bore the transparently Mayakovskian title Automobile in the Clouds (echoing the famous futurist’s “A Cloud in Trousers”) and inspired one reviewer in Petrograd to label the contributors “the Oscar Wildes of Deribasovaksaya Street.” Although Bagritsky would refine his technique in the years to come, youthfulness and vitality remained the hallmarks of his work. He was, in every sense, a romantic poet, who longed for adventure and sought out the sublime. No wonder, then, that he derived so much inspiration from the Black Sea. As Babel put it: “He’s just like his poems… He loves the sea, a sailor’s salty speech, and a fisherman’s boat on the horizon.”

In keeping with his love of adventure, Bagritsky supported both the February and October Revolutions of 1917 and joined the Red Army in 1919. His poems of the 1920`s and early 1930`s wed beauty with horror; some are purely romantic, others treat serious subjects — including violence, morality, and the place of Jews in Russian and Soviet society — with uncompromising honesty. Bagritsky died in 1934, in Moscow, after a lifelong struggle with asthma. The advent of Socialist Realism that same year would make such uncompromising honesty unacceptable, and even fatal.

The poem below, “Smugglers” (Kontrabandisty, 1927), may be one of Bagritsky’s most romantic offerings — a freewheeling sea chantey that glorifies the work of Odessa’s Greek smugglers, as well as (“more proper[ly]”) that of the patrolmen charged with tracking them down. As a proud Odessan, I’ve carried the poem in my head for decades, repeating its refrain over and over again. In my translation, I drew on the spirit of English chanteys and ballads, and found special inspiration in John Masefield’s “Sea Fever.”

Smugglers

Over fish, under stars,

the little boat races —

three Greeks are aboard,

smuggling goods to Odessa.

Jibing and tacking,

skipping over the waters,

are Yanaki, Stavraki,

and Papa Satyros.

The wind — how it whoops!

How it whistles right past —

sets the nails ringing,

rattles the mast,

and moves with a ripple

neath the hull in the dark:

“Wonderful trade! Excellent work!”

Let the stars sparkle,

let their light pour

on cognac, and stockings,

and condoms galore…

Aye, the Greek sail!

Aye, the Black Sea!

Aye, the Black Sea!..

Thief upon thief

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

The hour of midnight —

a dangerous time.

Three border patrolmen,

darkness and wind.

Three border patrolmen,

six eyes on watch –

six eyes on watch

and a fast motor launch…

Three border patrolmen!

A thief on the lookout!

Throw down the launch

in the Ottoman sea,

so that the waters

buzz at the stern:

“Wonderful trade!

Excellent work!”

So that the petrol,

like a bat out of hell,

shoots through the pipes

to the ribs and propeller.

Aye, starry midnight!

Aye, the Black Sea!

Aye, the Black Sea!.

Thief upon thief!

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

How I would love

to sprawl on the deck,

with the breeze in my whiskers,

in the fast-flying dark,

to see all the stars

glimmer over the bowsprit,

to shatter my voice

on the Black Sea’s argot,

to hear through the wind —

so bitter, so cold —

the tongue-twisting prattle

of the sentinel’s motor!

But perhaps it’s more proper

to spy on a thief,

with a gun in my fist,

as he flees through the mist…

To sense the strong wind

as it brushes my veins,

while I follow the sails

of thieves on the run…

Then, all of a sudden,

to meet in the night

a mustachioed Greek

without taking fright…

Aye, pound in my veins,

harder and harder,

my harborless youth,

my fury and ardor!

Let the stars rain

like blood from a wound!

Let me race onward —

a shot past the moon,

Let the waves sound —

a fanatical chorus!

Let my lips curl

round those venomous words —

I’ll sing till I’m hoarse,

so awfully free:

“Aye, the Black Sea,

wonderful sea!..”

1927

Pingback: Eduard Bagritsky’s “Smugglers” and Ryszard Krynicki in the TLS – Boris Dralyuk()