It should be no surprise that Ukraine’s political revolution has also given birth to a literary renaissance, one that is firmly connected to the the forces of contemporary technology.

One of the main causes for the recent explosion in modern Ukrainian literature is the political tension that the country is currently going through. This is a natural process. The surge in national consciousness, the torturous process of a society building a new identity, the emergence of the country’s intellectual elite to the forefront of the culture – these are all contributing factors. All of these events have transpired rapidly within the past two years and Ukraine has attempted a total overhaul of its system and society. The efficacy of this attempt can be debated, but one thing is certain – the publishing industry in Ukraine is experiencing a true revival. Many new publishing houses have opened, and even new talented authors have appeared on the literary scene. Some of these names have faded into the literary background, while others have been making an unprecedented impact, breathing fresh air into modern Ukrainian literature. Even looking at Odessa alone – which is not to imply that Odessa is not an important city in the context of writing – it will become quite obvious that we are witnessing the rise of a veritable “New Wave” of Ukrainian literature.

In these circumstances, it becomes especially important to differentiate between quantity and quality. On one hand, the revival of the literary community, its influx of diversity and the life it brings to the city is indisputably a positive thing. On the other hand, due to the sheer volume of creative output, we are bound to see a lot of mediocre attempts at poetry, shallow analytics and simply untalented writing. The popularity and omnipresence of the “blogosphere” and the social media in general are increasingly a defining factor in the production of literature just as they are in every aspect of contemporary culture. In particular, Facebook – a platform with enormous mass appeal – has become not only an arena of free speech for the city’s intelligentsia and creative spheres (such as Odessa opinion leaders Aleksandr Roytburd and Boris Khersonsky), but has now began to “manufacture” heroes on its own, dragging new names from obscurity and into the sudden spotlight. In fact, Facebook is turning into a veritable foundation of literary potential, and serves as fertile soil for emerging young authors to draw from.

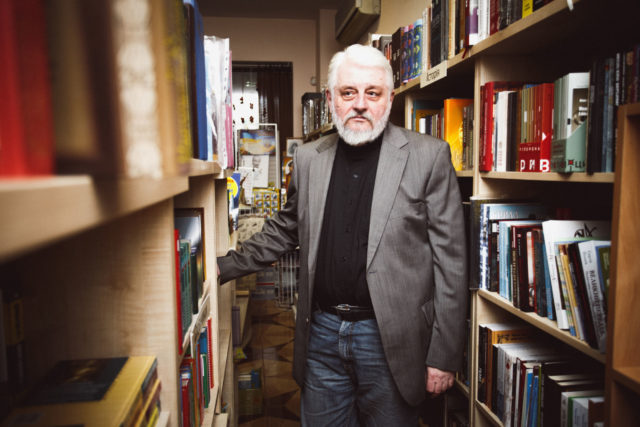

Of course, in the case of an established writer such as the poet Boris Khersonsky, Facebook cannot be said to have influenced his writing in any significant way. Khersonsky (a regular contributor to The Odessa Review) is one of the major figures in today’s literary Odessa whose first poems were published back in the late 1960s. His prose and poetry have appeared in many renowned publications throughout the years, including in the Russian expatriate press. Starting in the 1990s, he has been putting out new material regularly. In the early 2000s, Khersonsky became the laureate of several international awards, including the Austrian Literaris award for his masterful 2010 book “Family Archive”. For him, Facebook is just another platform for the dispersal of his poems, editorials and his notes as a psychiatrist as well as his historical and cultural investigations. A distinction must be made here between Facebook and other internet platforms with a similar purpose, such as LiveJournal, which has been fading from popularity in the Russophone world. Facebook provides one vital asset to creators which other media platforms don’t – the capacity of instant two-way communication. The author can gauge the public’s reaction mere moments after publishing his work. Discussions arise instantaneously, both on-topic and tangential ones. After all, this is the main purpose of creative works — to stimulate thought, to encourage the exchange of ideas, to hone the dialectic of a critical argument.

Everything changed two years ago as a result of the tragic events that swept the country. This was a watershed moment for Ukraine’s self-determination, and the support of the Ukrainian and international intellectual community was needed more than ever. During this time Khersonky’s personal Facebook, regardless of his intentions, became a battlefield of opinion for Odessa’s intelligentsia. It should be noted that it also made an impact outside of Odessa as well – his essay on the hypocrisy of Russia’s “brother nations rhetoric” made quite an impression in Russian literary circles.

Khersonsky on the other hand was very guarded about his Facebook page. He saw it first and foremost as a sort of interactive writers’ diary. It can be said that the platform helped him solve certain creative issues. In 2015, after the release of Khersonsky’s “Open Journal” the nature of this problem-solving process became obvious. It is doubtful that Khersonsky would have been able to collect the distinct texts comprising the work into one book if it was not for the fact that his Facebook entries from 2014 gave a clear and complete image of Odessa’s thoughts and reactions to the Euromaidan events. Khersonsky says about his book:

“This was a time that broke me apart…but did not manage to break me finally. From the fragments, I was able to construct a new meaning, a new identity. Facebook made this process transparent – maybe even too transparent, but what’s done is done. I understood this clearly once again, looking at the pages of my journal.”

At that point, during the “Revolution of Honor”, the Facebook page of another Odessa intellectual was garnering a lot of popularity: Aleksandr Roytburd. Probably the most important modern Ukrainian painter, Roytburd’s approach to his blog was entirely different from Khersonsky’s. He did not shy away from satire and ridicule. The writing style was intentionally flawed – no punctuation marks, drastically shortened and simplified semantic structures, a generous amount of profanity. Roytburd positioned himself as especially close to “the people” – and the people responded favorably. He discussed extremely complex topics in simple and down to earth terms, many of his points conveyed through his characteristic cynical, dark sense of humor. A public demand for a book by Roytburd arose. Of course, the public wanted this to be another collection of Facebook and blog entries, as this medium was proving to be a ruthlessly clear way of conveying a message and Roytburd’s posts were unique, insightful and politically biting. However, true to his individualistic nature, Roytburd refused to satisfy this demand. He would still release a book, which was presented at the 2016 Book Arsenal. His work is not a book in the conventional sense – rather, it is an extensive catalog documenting his entire creative path as an artist. Texts make up a significant portion of the book. They deal with modern Ukrainian art, Odessa art schools and artists, Roytburd’s autobiographical sketches and memories, an analysis of the city’s (and the country’s) current cultural situation. The text is of a high quality, characterized by the author’s bold use of metaphor and allegory, drawing parallels between his writing and painting style. The book makes for very interesting reading, and it is fairly evident that Roytburd honed some of its incisive, direct style from his writings and exchanges on Facebook.

Boris Khersonsky and Aleksandr Roytburd are merely the most famous and obvious examples. Their creative legacy was established well before the era of Facebook, and the social internet platform did not have any serious impact on their art rather serving as a conduit. But today’s literature is rife with bona fide “internet heroes”, whose rise to fame was facilitated by social media such as Facebook. Some of them have already been able to publish collections of their works, while others are still waiting for their moment in the sun.

Stas Dombrovsky’s example perhaps illustrates this phenomenon best of all. Praise of Dombrovsky is not often heard in Odessa. His world is a bleak place where thieves, addicts and other rejects of society are illustrated with supremely powerful writing and complex language reminiscent of Andrei Platonov. It is a world totally devoid of romanticism, even in its trite “criminal” variety. A world that promises a future that will surely only get worse. The Odessa publishing company Stellar took a risk when they released a collection of his poetry and prose, most of which was taken from the author’s Facebook page. However, that risk paid off. Presented in book format, Dombrovsky’s gritty observations took on a kind of sophistication and a deeper meaning. The bare nerves, the high tension of his writing created a startlingly powerful – if often dark and unflattering – image of the author’s worldview.

Another writer to come to prominence out of social media is Vitaliy Grinchuk who appeared in Odessa’s literary community recently and unexpectedly. It was after seeing his writings on Facebook that Sergey Bakumenko as well as Stas Dombrovskiy, started inviting him to their literary evenings, where Grinchuk easily outshone all the other authors. The audiences loved him: his texts had an attractive way of addressing the unpleasant realities while retaining a subtle Odessa charm. Stories about the working class Moldavanka neigborhood, old ladies, trams and neighbors were delivered with exceptional humor and an awareness of hidden aspects of life. Grinchuk’s tales are alive with real characters the likes of which have not often been seen in Russophone literature since the time of Maxim Gorky. But the most distinguishing feature of his prose is his wonderful philosophic rumination, as well as a signature tendency toward innuendo that gives the text the quality of a parable. Grinchuk’s writings have been published in periodicals and a complete collection of his stories would become a literary event of national significance.

The literary merits of social media platforms can certainly be debated. But one fact remains indisputable – it was the internet, and Facebook in particular, which has given us an entire lineup of new, vivid and gripping authors: Odessa’s Stas Dombrovsky and Vitaliy Grinchuk, Kyiv’s Lembit Koroedov, Gorky Luk, Pavel Belensky, and Yuliya Batkilina from Kharkiv, among many others.

Alexandr Topilov is a musician, critic, and author of the book ‘That’s all there is’.