The Ukrainian artist Fedir Krychevsky, who was a refugee, a very handsome man and a romantic spirit, became a symbolic figure within Ukrainian modern art. He was a master of historical painting and portraiture, and was one of the founders of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts in 1917. During his life, Krychevsky witnessed two world wars, the revolutions of 1905 and 1917, the end of the Russian Empire, the emergence of an autonomous and independent Ukraine with its own cultural institutions, revolutionary turmoil, anarchy, pogroms, changes of power, the establishment of the Soviet Union and establishment of the machinery of the Soviet regime. Despite all the cruelties of those times, or perhaps because of them, human dignity is the main theme of his works. This summer’s exhibition The Master And The Time: Fedir Krychevsky, presented at the National Art Museum of Ukraine from June 23rd to August 13th, takes a closer look at the artist’s work, life and times. It will display the original paintings and graphic art works of Krychevsky, as well as unique archival documents and photographs. This biographical text is based on the published memories of Eugen Blakytny (Nakonechny) who studied painting under Krychevsky and worked with him in the 1930’s.

Fedir Krychevsky was born on May 22, 1879 in Lebedyn, a town in the Sumy region in north-eastern Ukraine. His father Hryhorii, was a doctor of Jewish descent, but converted to Orthodox Christianity and married a Ukrainian woman, Paraskeva. Fedir’s brother Vasyl (1873 – 1952) was also a famous artist in his own right.

From his early childhood onward, Krychevsky was fascinated with Ukrainian folk decorative art and the vivid natural colors of magnificent Ukrainian rural landscapes. When teaching art and painting, he would often recount childhood memories to his students. As little boys, his father took Krychevsky and Vasyl to local town fairs where artisans would sell handmade textiles and ceramics and some local kobzar (Ukrainian folk musician) would sing ballads about the heroic deeds of the Cossack times. In addition to that, in his teens Krychevsky was a frequent guest to neighboring houses of descendants of Cossack gentry, families such as the Myloradovych and Kapnist, where he could view rich private collections of European art. Later on Krychevsky, as a mature artist, would always strive to synthesize folk and professional art in his own work, and to teach his students a similar approach.

Krychevsky received his education at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (1901) and the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1910). In 1901, he completed his graduation painting on canvas — Noah with Sons in the Vineyard. The young artist painted this scene — the sons laughing at the drunken naked father — as a typical motif from Ukrainian peasant everyday life, with grotesque and honest humor. Because the Moscow art school was quite democratic, Krychevsky received the title of a non-class (that is non-fee paying) painter.

In Moscow, Krychevsky made friends with Ivan Myasoyedov, an art student from the Poltava region. The new friends spent their vacations together, traveling all over Ukraine and portraying nude models (young peasant women) to improve their painting skills. The period of his studies was vivid and perfectly romantic.

The well known artist Grigoriy Myasoyedov, Ivan’s father, resided in the village of Pavlenky, in the Poltava region. While the young artists stayed at the Myasoyedov home, they would live according to a special daily schedule, combining painting practice with gymnastic exercises and weightlifting, healthy rest and food. They would wake up at 6 am, to do their physical exercises, have breakfast, and afterwards paint from life for 5 to 6 hours without interruption. Such a combination of physical exercises with art was associated at the time with classical antiquity — the worship of a healthy lifestyle and the beauty of the naked body were linked. Thus, Fedir, Ivan and other young enthusiastic artists would wear clothes that resembled ancient Roman togas, and would crown themselves with grapes while singing hymns to the good life.

In 1902, Krychevsky and Ivan Myasoyedov found themselves lucky enough to be present in London at the coronation ceremony of King Edward VII. The talented young artists were most likely included in the official Russian imperial state delegation not only because of their painting skills, but also because of their athletic handsome looks.

Impressions from the London trip can be indirectly found in Krychevsky’s Portrait of a Mother (1904) – namely, the obvious influence of a Victorian era masterpiece, painting in oil on canvas Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 by James McNeill Whistler (it was painted in 1871 and is colloquially known as “Whistler’s Mother”). Krychevsky’s Mother is much like the original symbolist painting seen to be wearing a black dress and sitting turned to her left side, with her image seen in profile. However, Krychevsky searched for his own approach with the subject matter. He created a contrast between the dark silhouette of the dress and the vivid richness of the milieu in which the most attractive element is a colorful Ukrainian kerchief. Krychevsky’s Mother is much more emotional then Whistler’s depiction, and it fully abides with the Ukrainian painting tradition which is inclined to express intense feeling through color.

Twice Krychevsky started studying at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts. The first time he entered the class of the renowned artist Ilya Repin, but had to leave due to health issues. The cold and humid climate of Saint Petersburg often had a bad influence on the physical and mental well being of Ukrainian newcomers who were used to warmer weather. His second attempt to enter into the Academy was successful however.

By 1910 Krychevsky was finishing his artistic studies. Among his graduation works was the painting The Bride, which features scene depicting the dressing of a bride for a traditional Ukrainian wedding. The painting not only illustrated folk customs, but also conveyed ideas of deeper national aspirations. The image of the bride standing in the center and accompanied by bridesmaids is full of dignity and young vital power. It might be perceived as a symbolic Ukraine, happy and magnificent as it should be, according to the artist’s vision.

After a year-long journey abroad to European cities, granted as a grace gift to successful alumni of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, Krychevsky returned to Ukraine. He settled in Kyiv and worked as a professor and director at the Kyiv Art School from 1914 to 1918.

The revolutionary events that began in 1917 and which lasted in Kyiv until 1920 were not conducive for creative activity however. In 1918 Krychevsky became the rector of the newly established Ukrainian Academy of Arts. Immediately, the new institution faced a lack of funding. During the most discouraging months, Krychevsky would leave on his own to return to his native village in Shyshaky, Poltava region. The local nature and its monumental landscapes would inspire the master and only there the artist could work freely and fruitfully.

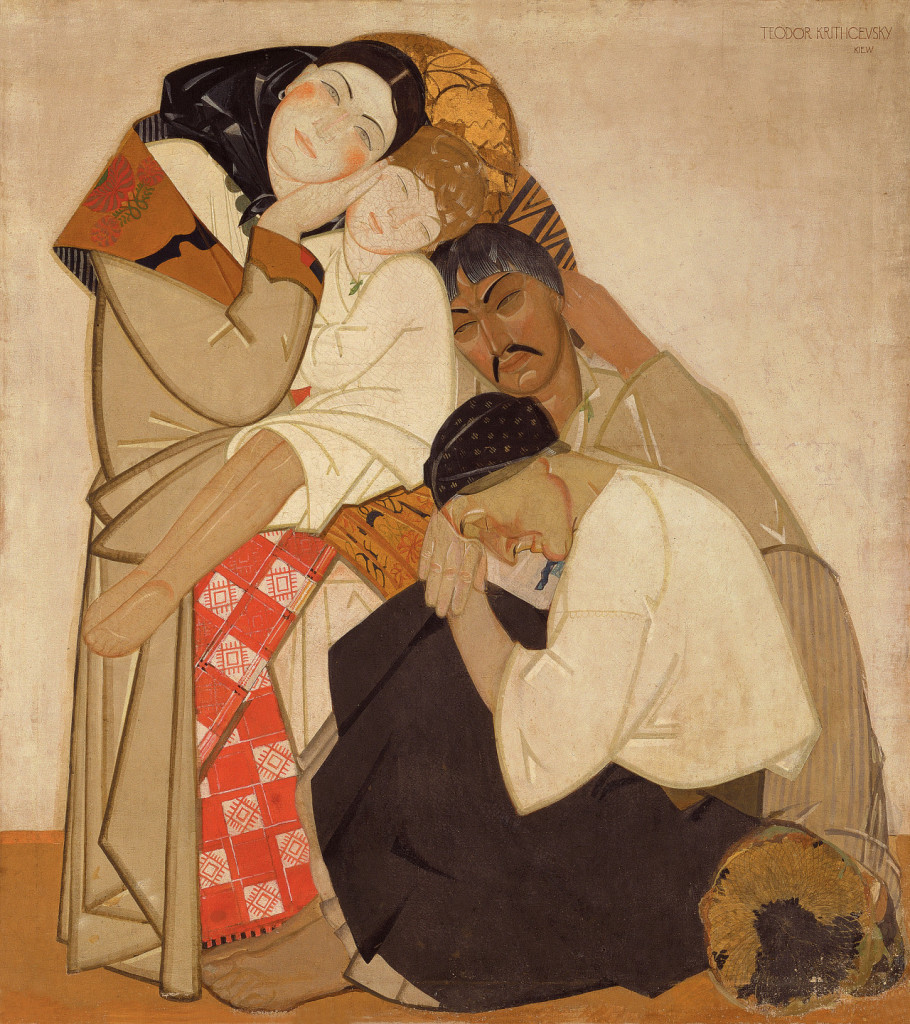

In the 1920’s, during the so-called “Ukrainian Renaissance” period, Krychevsky continued to teach at the Kyiv Art School, but at the same time he also studied fresco painting and created a series of paintings in tempera technique. The most significant work of the period was the triptych Life (1927). Here the author chose a broad subject, with deep philosophical meaning embodied in Art Deco and national themes. In the work he touched on the themes of love, family happiness and the homecoming of a son, injured during the war. That is how Krychevsky, who himself had experienced both fortune and suffering, interpreted life. The triptych was exhibited at the 1928 Venice Biennale and received warm welcome from international art critics.

By the end of 1920’s, the Soviet regime had become stronger and gradually the sovietization process had began to pervade all spheres of social life, creating more and more limitations on creative freedom and artistic activity. The Ukrainian Renaissance was effectively terminated by the events that are now known as the “Executed Renaissance” (“Rozstriliane vidrodzhennia”) when thousands of outstanding Ukrainian writers, artists and scientists were repressed, arrested or shot during the Stalinist purges of 1930 – 1940. The Holodomor, the artificial and politically motivated man-made famine of 1932 – 1933, cost Ukraine at least another 3 – 7 million lives, though many historians speculate that the actual figures were much higher. The Ukrainian peasants were forced to adopt Stalinist collectivization and industrialization plans.

In 1926 – 1932 Fedir Krychevsky wrote his masterpiece Self-Portrait in White Sheepskin Coat. It is a manifesto of a Ukrainian artist who is guarding national culture and identity. Around the same time Krychevsky completed his monumental painting Dovbush. It portrayed a famous Ukrainian folk hero of the 18th century, the peasant leader Oleksa Dovbush who rebelled against the regional wealthy landlords and gentry and was often compared to Robin Hood. Besides Dovbush, the painting includes many characters — common Hutsuls, who are a local ethnic Ukrainian group residing in the Carpathian mountains. Krychevsky skillfully conveyed the Hutsuls’ high-minded nature and nonconformity. The large several-meter tall canvas was exhibited in the Kharkiv Art Museum, but was tragically lost during World War II.

The Native Land (1935), another large canvas by the master, portrays a woman holding a child, standing among the high trees against a picturesque background. It is a utopian and dreamy fantasy, reflecting the artist’s belief that his native land, Ukraine, must have a happy future.

In his later works, Krychevsky always made an effort to avoid direct Soviet propaganda themes. Even when Krychevsky was commissioned to paint the canvas Conquerors of Vrangel (1934 – 1935) about Red Army troops defeating the anti-Bolshevik Pyotr Vrangel’s troops in Southern Ukraine, the artist managed to create an ambiguous image. According to the unofficial author’s concept work, in the center of the painting he portrayed a Ukrainian, on the left is his brother — a Belarusian, and on the right — the Russian who is standing separately and facing away from both.

The relationship between the artist and the conformist administration of the Kyiv Art Institute was deteriorating. Since Krychevsky was an non conformist defender of Ukrainian culture, his foes were actively searching for compromising evidence and finally accused him of harboring a sympathetic attitude toward the short lived independent Ukrainian State that had been led by Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky in 1919. During the late 1930’s, such political accusations basically constituted a death sentence.

An old friend whom Krychevsky had helped during his studies in Saint Petersburg, wound up saving Krychevsky from the Stalinist purges. While he attended the academy, Krychevsky had helped a fellow student combat a disgraceful practice. At the beginning of the 1900’s, Saint Petersburg Art Academy students were unfairly exploited by their professors. They would make high-quality copies of world-known art masterpieces, and were paid mere pennies for the labor. The professors, on the other hand, would sell the excellent copies for decent money and would have the paintings be exhibited at the Hermitage. As Krychevsky had enjoyed patronage in the highest circles of the Imperial Court, he was able to force the administration of the Academy to return all the money gained from one such well-sold copy to a poor student — Isaak Brodsky.

During the terrifying time of the 1937 Stalinist purges, Brodsky was by this time already a famous artist, and as a favorite of Joseph Stalin, was also the first painter to be awarded the Order of Lenin. In the winter 1937 he unexpectedly came to Kyiv and visited the Kyiv Art Institute. There, at an official administrative meeting, he severely criticized and condemned the administration of the Institute and thus saved not only the reputation, but also the life of Krychevsky.

Rescued by fate and friendship from the Stalinist repressions, Krychevsky was able to continue his work. In 1937 – 1940 the artist created another masterpiece, Dreamy Kateryna, which was inspired by a tragic poem of Taras Shevchenko. It featured a gorgeous young peasant girl symbolizing innocence, purity and the beauty of youth — the perennial themes of the artist. The girl dreams about commonplace happiness: children, a family and her own home. In Shevchenko’s poem, however, Kateryna ends with a cruel fate when she is betrayed by her beloved and faces a life of wandering and neglect.

Krychevsky stayed in Kyiv throughout the Nazi occupation. With the Soviet army approaching to retake the city in 1943, he attempted to emigrate west in the footsteps of his elder brother Vasyl Krychevsky. As he attempted to settle in Europe, he fell ill and was captured by the Soviet SMERSH (abbreviation of “death to spies”) the special troops of the KGB. For a year he was imprisoned in Königsberg (Kaliningrad) before being released..

Miraculously, in 1944 Krychevsky returned to Kyiv. By this time he was seriously ill, exhausted, homeless and deprived of all his pre-war positions and titles. The great artist died three years later in Irpin, a suburb of Kyiv.

Danylo Nikitin is a curator and research associate at the Ukrainian National Art Museum in Kyiv.