The penal institutions in which the Soviet Union imprisoned dissenters had as their purported aim not simply the act of isolating and punishing political opponents but also of “correcting”, or “re-educating” them. It is therefore ironic that contrary to the intentions of its operators, the Gulag became a de facto university for free thought and a space of fecund intellectual and political cross-fertilization. It brought together some of the Soviet empire’s most original, courageous and enterprising individuals, people from vastly different ethnic and regional backgrounds, and provided them with an opportunity to interact. It gave them the opportunity to take part in an ongoing process of mutual self-discovery, self-development and self-empowerment. Who would have imagined that in the harsh conditions of such improvised discussions, “seminars” and joint actions, a unique forum for a novel Ukrainian-Jewish encounter would be created and would serve as an incubator for future Ukrainian-Jewish Understanding And Cooperation.

In the post-Stalin era Ukrainians who had been accused of “nationalism” consistently formed the largest group of political prisoners within the USSR. These included: participants in the anti-Soviet resistance movement of the 1940’s and early 1950’s; members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, or UPA, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalist, OUN, as well as members of the banned Ukrainian Catholic Church; patriotically minded intellectuals imprisoned in the 1960’s and early 1970’s; and finally representatives of the Ukrainian human rights and national rights movements that crystallized in the 1970’s.

By contrast relatively few Jews in were imprisoned for asserting their Jewish identity or for taking part in the Zionist movement. Following Stalin’s death in March 1953, the anti-Semitic repressions that followed the notorious “Doctor’s Plot” came to a relative halt. Those who ended up in the corrective colonies, prisons, psychiatric hospitals and places of exile were imprisoned mainly for non-conformism (both political and artistic), and in later decades for their human rights activism. The situation changed after the 1967 Six-Day War when more and more Soviet Jews sought to emigrate from the Soviet Union but were refused permission to leave. Many of them thereby became disaffected “refuseniks”. In June 1970 a group of sixteen refuseniks (two of whom were non-Jewish) unsuccessfully attempted to hijack a small aircraft to fly them from Leningrad to Sweden. They were given heavy sentences for “high treason”, including, initially, the death penalty, and the much-publicized case catalyzed the nascent refusenik activism. Subsequently, campaigners for the right of Jews to emigrate were prominent in the Soviet human rights movement and among political prisoners.

While Ukrainians and Jews imprisoned for political reasons in the post-Stalin Gulag shared a common temporary fate, their backgrounds and sensibilities differed. They likewise did not share a common view of the past or of ultimate concerns. Stereotypes and prejudices cultivated by the Soviet and Nazi totalitarians, as well as by Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish bigots and xenophobes, persisted among both groups. The divergences in their political outlook and priorities stemmed from their own particular understanding of the past and the challenges of the present. Yet their shared predicament as political prisoners and determination to persevere and survive created the basis for solidarity. In turn, this process encouraged a fruitful exchanges of views, a sensitization to one another’s concerns and paved the way for mutual understanding and cooperation.

In the 1950’s Jewish inmates of the Gulag witnessed the remarkable resilience of the UPA veterans and representatives of the clergy and hierarchy of the Ukrainian Catholic Church. Contrary to Soviet propaganda, they did not encounter Ukrainian anti-Semites, Holocaust deniers, or apologists for the Nazis. The Jews found that they had no problems getting on with them. And in the 1960’s and 1970’s the next generation of Soviet dissenters who ended up in the Gulag also quickly discovered that the anti-Ukrainian nationalist and anti-Jewish/Zionist myths being generated by the Soviet regime, aimed in no small part at sustaining enmity between the two peoples, did not hold up in frank and open discussions. Such open dialogue between the Ukrainian and Jewish political prisoners would never have been possible outside of the Zone (Gulag).

Former Jewish prisoners, such as Avraham Shifrin, brought out heroic images of Ukrainian modern-day martyrs, such as the Ukrainian Catholic Metropolitan (later Cardinal) Josyf Slipyj. By the 1970’s Jews were not only standing side by side with their Ukrainian colleagues in the struggle for political prisoner status, but also transmitting to the outside world news about, and even the works, of leading Ukrainian dissenters, such as the poet Vasyl Stus. The Jewish dissidents Mikhail Kheifets and Arie Vudka memorized his poems, as well as those of other Ukrainian poet prisoners and on emigrating from the USSR made them known to the wider world. Having arrived in Israel, some of the Jewish former political prisoners, most notably Yakiv Suslensky, sought to improve attitudes towards Ukrainians and their example and openness to dialogue also had a corresponding positive impact on the Ukrainian diaspora. With the appearance of a Jewish dissenter, Iosif Zisels, in the Ukrainian Helsinki Group which formed in 1976, the dissident Ukrainian movement for human and national rights appeared to come of age. Zisels was the irrepressible representative of a political nation in the making, a process which was subsequently accelerated in the late 1980’s by the socially inclusive (as opposed to exclusive), strategy adopted by Rukh (Ukraine’s Popular Movement for Renewal).

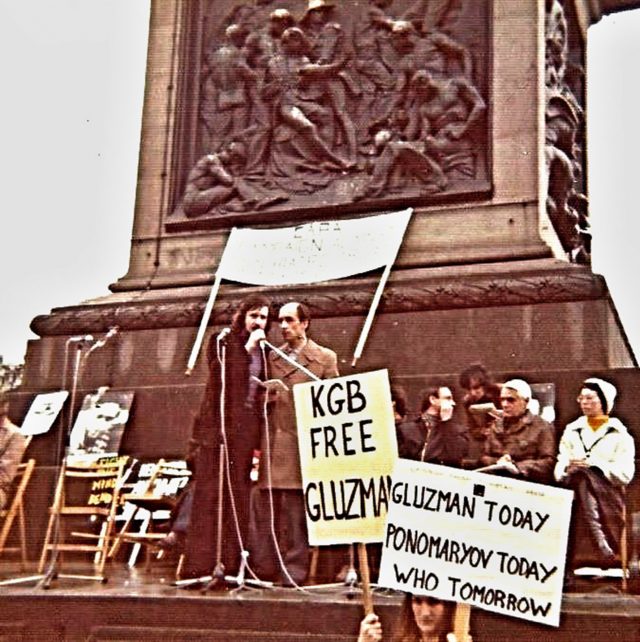

The total number of Jewish and Ukrainian prisoners who were actively involved in this process of rapprochement and alliance-building may not have been that large, no more than two dozen and one hundred from both sides respectively, but it was the quality and the quantity of the participants that mattered. On the Ukrainian side they included such influential icons of the national movement as Viacheslav Chornovil, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Vasyl Stus, Ivan Svitlychny and Sviatoslav Karavansky. On the Jewish side they included Yakov Suslensky, Mikhail Kheifets, Arie Vudka, Boris Penson, Semen Gluzman and Iosif Zisels. Several of the Jewish former political prisoners later recalled how their Ukrainian colleagues had helped them better appreciate the way in which human and national rights were interconnected. That process helped them to rediscover, or reaffirm, their Jewish identity, in contrast to the Sovietized and Russified forms which were tolerated by the Soviet system. For his part, Stus, who shared a pretrial cell in Kyiv with the psychiatrist Gluzman noted that the latter had helped him practically by teaching him the basics of psycho self-analysis. He proudly noted that he had never been an anti-Semite and that the Jews he met in captivity were also not inherently Ukrainophobes.

Incidentally, two of the leading figures in this Jewish-Ukrainian encounter in the Gulag, Sviatoslav Karavansky and Yakov Suslensky, were from the Odessa region. Karavansky, who spent a total of almost 30 years in the Gulag was a staunch defender of Ukraine’s rights, especially its language and culture. In 1966 he filed a formal complaint to the Head of the Council of Nationalities of the USSR Supreme Council in which he elaborated how Sovietization and Russification were aimed at making Ukrainians docile Russian-speaking junior cousins of the Russians. His complaint also underlined that the process was aimed at assimilating other nationalities into the dominant Russian culture, resorting for example to discriminatory policies against Jews through the closure of their cultural institutions and restrictions on their access to secondary and higher education. Karavansky’s wife, the microbiologist Nina Strokata, was arrested in 1971 for her own human rights activities. She was given a four-year-sentence and ended up in the Mordovian corrective colonies alongside other women political prisoners, including the refusenik “hijacker” Sylva Zalmanson.

Suslensky was born in the Odessa region and studied in Odessa. He became a teacher of English in nearby Bendery and was imprisoned in 1970 along with a Jewish colleague, Iosif Mishener, for the crimes of political non-conformism and defending human rights. In the camps, this Ukrainian-speaking Jew formed close bonds with his fellow Ukrainian dissenters. On completing his sentence and emigrating to Israel, Suslensky became a dynamic advocate of Jewish-Ukrainian understanding and cooperation. He founded an Israeli Society for Ukrainian-Jewish Relations and a journal for this purpose called “Dialohy” (Dialogues). Another refusenik, Israel Kleiner from Kyiv, also made an important contribution in this area. Both Suslensky and Kleiner (who managed to avoid imprisonment) published articles in the West describing the ongoing rapprochement between Ukrainian and Jewish political prisoners in the Gulag.

The Ukrainian-Jewish encounter in the Soviet camps resulted into a mutual respect which frequently also developed into admiration for each other. Arie Vudka described fellow political prisoner Sverstyuk as “an angel in that hell” as well as “a sunbeam in the deep darkness of night”. Gluzman, inspired by Stus and another leading Ukrainian poet, Ihor Kalynets, began writing poems in Ukrainian and devoted two of them to Kalynets and Svitlychny. For his part, Kalynets dedicated one of his poems to Sylva Zalmanson. In the late 1970’s Sverstyuk aptly summed up what had occurred: “Above all, I consider the Ukrainian-Jewish alliance from the ethical perspective as a turn towards positive sensibilities, as the dialogue of equals “freed from” the false garb of imitating alien concepts, foreign truth and somebody else’s interests”.

So what did this Gulag experience amount to? The contradictory examples of the “Ukainophobe” Joseph Brodsky and the “Ukrainophile” Kheifets are more than apt to illustrate the radically different possible outcomes of the Jewish-Ukrainian encounter. Having become an American, the celebrated poet Brodsky appears to have detested Ukrainians and what they represented and upheld the traditional Russian imperial position. In his notorious poem of detestation against Ukrainians on the occasion of their achievement of independence, he rehearsed all the familiar prejudices and stereotypes. Yet Kheifets, who was also a Russian Jew, and who had himself been imprisoned for admiring Brodsky as a poet and compiling his works, became in the Gulag a great friend and sympathizer of the Ukrainians. He did a tremendous deal to make their plight and achievements known to the outside world. One wonders therefore whether Brodsky, if he had ended up in the camps for political prisoners (he was imprisoned on the cynical, non-political charge of vagrancy) and experienced the Ukrainian-Jewish encounter within them would have taken a different view of Ukrainians and of their national aspirations.

In short, Soviet political intolerance carried an implicit Russian chauvinistic tinge, and paradoxically provided an unlikely forum — the Gulag — for the more committed and liberal Ukrainian and Jewish dissenters to meet and bond. Their interaction both informed and drew upon the examples in this regard being set outside this closed zone by such courageous figures as the Ukrainian literary critic Ivan Dzyuba. The critic was a close friend of the leading Ukrainian political prisoners, and in September 1967 he delivered an impassioned plea in Babyn Yar for Ukrainian-Jewish understanding and reconciliation, during which he denounced anti-Semitism. Just before — and certainly after Ukrainian independence was achieved — former Ukrainian and Jewish political prisoners helped, and continue, to instill the values of tolerance and inclusion that have helped shape the building of a modern democratic Ukrainian political nation. Today’s new independent Ukraine has its head of government a Ukrainian Jew, prime minister Volodymyr Groysman, and former Jewish political prisoners Gluzman and Zisels, and sociologist Leonid Finberg, are among the authoritative Ukrainian Jewish representatives of its vibrant civil society and human right community.

Bohdan Nahaylo is a British-Ukrainian scholar, journalist and veteran Ukraine watcher. He has worked for Amnesty International, Radio Liberty, the United Nations and Democracy Reporting International. He combines his professional work as a political analyst and policy advisor with a passion for literature, music and culture.