The head of the Ukrainian Institute in London writes about the reception of the 100th anniversary of the 1917 revolution in London. In autumn 2017, the Institute will continue its series “The Century of Ukrainian Revolutions: 1917-2017,” a curated selection of talks, book launches and screenings in London.

Images of the 1917 Russian Revolution have flooded the London of 2017. Marching Bolsheviks and Red Army soldiers point at me from posters on every corner of the British capital and bring with them a strange feeling of returning to the Soviet Ukraine of my childhood.

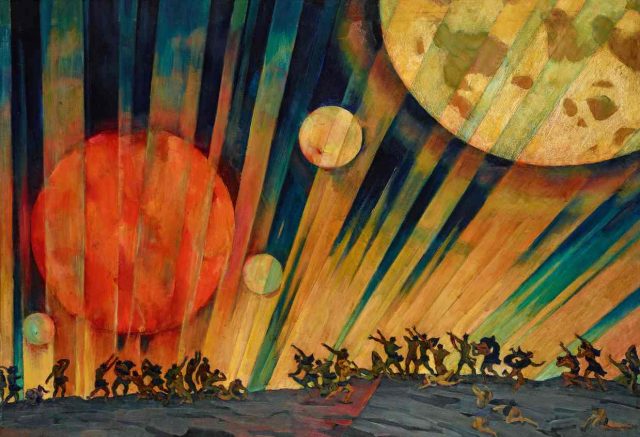

The Royal Academy of Arts blockbuster show, “Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932,” dazzled its audience earlier this year with a magnificent display of arts and cinema. Meanwhile, the British Library’s “Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths” exhibition unearthed interesting archival documents and artifacts from its collection. Towards the end of the year, “A Red Star Over Russia,” will be the headliner attraction at the Tate Modern gallery. Dozens of less high-profile events are also taking place in the British capital.

There has been little mention of Ukraine in this flurry of Russian Revolution retrospectives. For example, Kazimir Malevich was an ethnic Polish avant-garde artist born in Kyiv, who spent his formative years in Ukraine and spoke Ukrainian. His art took up a whole room at the Royal Academy, but visitors learned that he was “Russian,” despite the fact that many of the paintings on display refer to his “Kyiv period.” Olexander Dovzhenko, the renowned Ukrainian film director whose films focused on Ukrainian material, was branded merely as “Ukrainian-born.”

Cultural mapping aside, there is no mention of Ukraine as a major battleground during the tumultuous events of 1917. Ukraine’s statehood bid and its struggle for independence between 1917 and 1921 are not mentioned anywhere, nor is the fact that Ukraine was a major theatre for a so-called civil war involving a dizzying array of opposing sides and nationalities.

This is no surprise and Ukrainians should not be deluded into thinking that they will ever ever be allocated a place in this grand narrative. All exhibitions of this kind take years to prepare and involve major Russian galleries and museums along with funding from Russian oligarchs. Moreover, many British curators have an inherent bias against events and arts originating in non-Russian parts of the former Tzarist Empire, typically placing them under the Russian umbrella or ignoring them altogether.

Ukraine needs to begin constructing its own narrative of the 1917 events and to project it to the international audience. It won’t be easy: few westerners, apart from a narrow academic milieu, know about national struggles taking place in other parts of the Russian Empire shortly after the 1917 February Revolution and later in the aftermath of the Bolshevik-led uprising. The academy in the West still has to go through the process of “internal decolonization,” a term coined by an American Professor Mark von Hagen. “Let us start with an inconvenient fact that already in December 1917 the first Russian Socialist republic attacked the first Ukrainian Socialist republic,” explains Professor von Hagen. Very shortly, the grand project of building a fair society turned into a one-party, one-nation dictatorship. This imperial project was completed in 1922, with the creation of the Soviet Union.

Inside Ukraine, a great deal of historic research focusing on this period has been done. Little of it, however, is known in the the west. The shelves of both popular and academic literature on the 1917 revolution remain Russia-centric. Nonetheless, the Ukrainian history of the period is no less gripping. It was right in the eye of the storm of an enormous conflict cutting across empires and societies and involving many players: Ukrainian nationalists, Bolsheviks, the Whites, Western interventionist forces as well as the anarchists. There’s plenty of material for academic research, popular fiction and films, troves of untold personal stories, of which only occasional snippets, like Isaak Babel’s “The Red Cavalry,” are translated and known in the West.

Ukraine might find that awakening westerners’ interest in this period of history is easier achieved through art history. Its cultural heritage of the period — its avant-gare cinema, visual arts and literature — are highly original and offer an interesting take on European modernism. It is important to raise and to maintain the debate about the Ukrainian dimension in the complex artistic identities of well-known giants of the avant-garde such as Kazimir Malevich, Olexandra Ekster, Olexander Arkhypenko and many others. It is even more important to start introducing undisputedly Ukrainian artists, such as Fedir Krychevsky, Olexander Bohomazov, and the Boichuk brothers to global audiences.

While mounting a majorartexhibitionabroad is an expensive and technically complex undertaking, there’s another area of Ukraine’s cultural heritage which is sure to be as impactful but which requires fewer resources. It is the Ukrainian avant-garde cinema of the 20’s and it should rightly become a lynchpin of the Ukrainian revolution narrative. It has everything: remarkable historical context, first class names, like Olexander Dovzhenko and Dziga Vertov and a wide range of incredible films, some of them completely unknown and never shown in the West.

In this field, Ukraine has done its homework: thanks for the efforts of the National Dovzhenko Centre, the films have been beautifully restored and remastered and turned into an attractive vintage product as well as framed with a well-informed expert comment. The films were also given a second lease on life thanks to a new music soundtrack created by contemporary Ukrainian musicians. One such project has enjoyed great success in London in recent years: it involved the screening of Dovzhenko’s masterpiece “Earth” played to the accompaniment of music of the cult favorite Dakha Brakha band. The Dovzhenko Center has many more projects of this sort under way.

The 1917 Revolution is a complex subject. Historically, Western left-wing intellectuals tend to glamorize it, extolling the “freedoms” it brought to the working class and peasantry. That process stems back to a long intellectual and artistic tradition, originating inside the Soviet empire and is illustrated by “The Monument to Three Russian Revolutions” by the Ukrainian avant-garde artist Vasyl Ermilov. Recently on display in London, it also features two mangled teacups taken from a destroyed house in today’s eastern Ukraine and placed on top of this shining edifice of the Revolution. It is an ironic reality check provided by Nikita Kadan, a contemporary Ukrainian artist who curated the “Postponed Futures,” exhibition of Ukrainian avant-garde art at the “Grad,” London-based private gallery.

Making the past present and projecting it into the future is the key in building this new narrative of the “Ukrainian Revolution” which extends all the way to the Revolution of Dignity of 2013-14 and beyond, into a revolution that is needed to construct a viable Ukrainian political identity and functioning modern state.

Marina Pesenti is Director of the Ukrainian Institute in London.