Mikhail Vrubel was one of the great Russian artists of the 19th century. His association with Odessa is not often spoken about, but the artist spent creative periods here. This article is part of Yevgeniy Demenok’s Odessa Review column on the history of the Modernist movement in Odessa and Ukraine.

It is astonishing, but until recently, the majority Odessites did not know that the great painter Mikhail Vrubel was closely associated with our city. If you ask an educated resident of Odessa — and all Odessites are well educated — about the relationship between Vrubel and Odessa, you will almost certainly receive puzzled silence in reply.

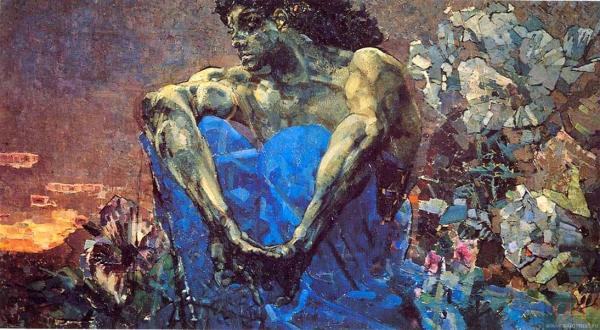

Such ignorance is all the more strange given that Odessa tends to claim connection to any significant historic personality, even those who only visited the city briefly. But in this case, we have a great artist who lived here for five of his school years; studied at the school of drawing; later, as a mature artist, here began work on the famous “Demon”; wanted to open an art school in Odessa with his friend Valentin Serov; visited his parents, who lived in the city for almost ten years…

The ice was broken a few years ago: in March of 2012, through the efforts of this author, a memorial plaque to the great artist was placed at 18 Sofiivska Street and a few Odessan publications dedicated articles to him.

Mikhail Vrubel came to Odessa because of his father’s work in the Tzar’s military service. Alexander Vrubel, whom the artist resembled in appearance and did not at all resemble in character, was a line officer who took part in the Crimean campaign, and later became a martial lawyer.

The work of Vrubel’s father demanded frequent relocation: Mikhail was born in Omsk, then lived in Astrakhan, St. Petersburg, three years in Saratov, then St. Petersburg again… At the end of 1869, the family moved to Odessa, where Mikhail attended the Richelieu Gymnasium, then located on Sadovaya Street in the house of Fundukley. In 1874, he graduated with a gold medal.

Mikhail Vrubel’s talent for art became evident early — in St. Petersburg, the eight-year-old boy was taken by his father to drawing classes at the Society for the Encouragement of Arts. A year later, in Saratov, he studied with a drawing teacher from the local grammar school, who taught him sketching from nature. In Odessa, Mikhail Vrubel attended the drawing school of the Society of Fine Arts. The school was headed by Friedrich Malman and the teachers were: academician Karneev for painting, academician Gornostaev for architecture, Milan Academy artist Ludovic Iorini for sculpture and ornamentation, an artist from the Munich Bauer Academy for drawing.

For a time, intensive studies at the Gymnasium distracted Mikhail from drawing — he became fascinated with natural sciences and history. Of particular interest are Mikhail’s letters to his elder sister Anna, who was studying at a pedagogic course in St. Petersburg. The image of the future artist emerges in five letters sent from Odessa between 1872 and 1874: “a typical overachiever, a bit of a dandy — to the extent natural for youthful dalliance, sociable, well-read, with diverse musical-theatrical-literary interests, flaunting foreign catchwords and comical Gallicisms, enjoying artful epistolary displays not so much from an excess of literary imagination, but from a desire to be amusing in the boring genre of family correspondence.” Vrubel is oppressed by Odessa’s provincial life: “A thousand, thousand times I envy you, dear Anyuta, that you’re in St. Petersburg: can you comprehend, madam, what it means for a person sitting in this thrice-damned Odessa, with tired eyes looking at all its ridiculous peoples, to read letters from St. Petersburg, which seem to be breathing with the freshness of the Neva. Parbleu, madame!” — he writes in a letter dated October of 1872. Here’s another quote: “To get away, in truth, from this Odessa, which with its commercial and indifferent views on everything is starting to corrupt my own” — this in the winter of 1874, shortly before leaving for St. Petersburg. What is expressed in these words: youthful posturing and maximalism, or a realistic assessment of the situation? Probably, a little of everything. The young city, founded as the southern sea shipping gate of the Empire, was indeed making money. Only later, the Partnership of Southern Russian Artists would be formed, Vladimir Izdebsky would hold his famous salons… But at the time, the drawing school did not even have a permanent address and survived on philanthropic contributions.

Still, Mikhail Vrubel’s missives to his sister indicate that in Odessa he attended theaters, the opera, exhibitions; painted portraits of relatives; spent time with local artists. The letters testify that cultural life in Odessa, though not the same as in St. Petersburg, did in fact exist.

It was to Odessa that Vrubel would come from Kiev to heal his spiritual wounds, returning with the intention of staying forever, inviting best friend Valentin Serov to join him. After graduating from law school with a gold medal, Vrubel enters the Academy of Fine Arts, the studio of P. P. Chistyakov — the very same Chistyakov who trained three generations of great Russian painters: Vasnetsov and Repin, Serov and Vrubel, Kustodiev and Borisov-Musatov. Later, Vrubel is invited to Kiev, to paint and supervise the restoration of the frescoes of St. Cyril’s Church — a huge amount of work. The client was Professor Adrian Prahov, with whose wife, Emilia Prahova, Vrubel fell in love. This love was fatal for Vrubel – the unrequited feeling caused him such suffering, that to distract himself, he would cut his chest with a knife.

To find relief from this anguish, the artist travels to Odessa. Vrubel stayed in Odessa for several months — from July to December 1885.

That Vrubel was brought to Odessa by a “matter of the heart” is supported by his letters to his sister, and their father’s letters to her. Vrubel wrote to Anna from Venice, where he worked from autumn of 1884 until spring of 1885:

“In short, I can not wait until the completion of my work, to return… And why such a great wish to come back? It is a matter of the soul and I will explain when we meet in the summer. I only hinted it twice to you, and haven’t said anything to anyone else.”

The concerned father, often not understanding the motives of his son’s actions and trying to help him, writes to Anna from Kharkov, where the family was living:

“… Misha is unemployed, I am inviting him to stay with us — he can paint the conceived picture here, life will not cost anything, no worries about money that have distracted him from work, what could be better? No and no. He is staying in Odessa. Definitely — ‘cherchez la femme.’ [look for the woman (fr.).]”

The “conceived picture” is the famous Vrubel “Demon,” on which he began work while in Odessa.

The only surviving letter of Vrubel’s second “Odessa” period retains the address where he lived: 18 Sophiivskaya Street, apartment 10. Valentin Serov, who came to visit his bride Olga Trubnikova, stayed in the same house. He writes to his friend and Vrubel’s acquaintance, painter Ilya Ostrouhov, on September 8, 1885:

“… You see, I have many reasons to go there, not to the Crimea itself, but to Odessa. By that time my sisters will be there, and you can’t imagine how I wish to see them. I will also meet there my friend Vrubel, whom I need to see.

By the way, he advises me to ditch the Academy, move to Odessa, where they seem to have a good circle of artists: Kuznetsov, Kostandi and so on and so forth, and apparently they want to arrange something like the Dzhideri academy in Rome (you’ve probably heard of it) — but, that’s secondary, I will see how it goes, but the question is, how to get there.”

Then begins the work on “Demon.” Serov recalled that Vrubel worked on the background of the picture. Having bought a few photos with mountain views, he arranged them in different ways, making complex patterns and trying to imagine the landscape against which the Demon would sit. The first few versions were subsequently destroyed by the artist, striving for perfection.

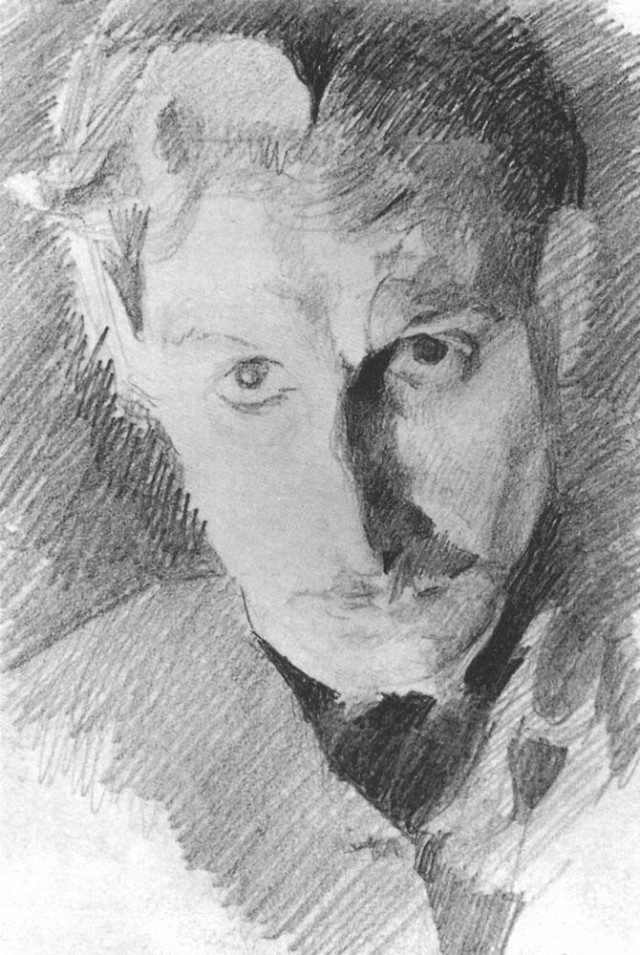

In addition to working on the large painting, Vrubel makes a series of sketches and watercolors in Odessa: watercolor “Port of Odessa,” four pencil self-portraits in various stages of completion, an unfinished portrait of Serov, and numerous sketches from nature. N.A. Prahov (Adrian Prahov’s son) wrote in his memoirs that Vrubel always carried with him a little album, in which did pencil sketches. About the portrait of Serov, Mikhail would say: “We lived with Serov together in Odessa, saw each other every day, had been friends for a long time, I knew his face well and therefore did not start with him, but with the tie and the forelock of hair, falling in three strands onto his forehead, that interested me. I thought I’d finish the next day, but something interrupted us, and a few days later Serov left for Moscow.”

N. A. Prahov recalled Vrubel’s words: “Odessa life suited neither of us. Commercial interests consumed the attention of the local community, but we wanted to live where artistic interests are placed higher.”

Perhaps this was true, but it was not the main reason for the artist’s departure from Odessa. Vrubel was drawn to Kiev by many circumstances — the remaining feelings for Emilia Prahova, better earning opportunities, and, of course, the possibility of taking part in the decoration of St. Volodymyr’s Cathedral.

The Partnership of Southern Russian Artists would be organized in five years — in 1890. In 1894, Valentin Serov would become a member.

The third “Odessa” period of Vrubel’s life was very short — just over a month. The artist came to visit his parents after his stay in Italy.

Vrubel’s father already knew about the trip that Mikhail took with Sergey Mamontov, son of S. I. Mamontov, to Italy. They stayed near Genoa, and on the way back to Russia – by sea – visited Naples, Brindisi, Piraeus (Athens) and Constantinople. Arriving in April just before Easter, the artist lives with his relatives in Odessa until mid-May. Alexander Vrubel writes in a letter to Anna on April 19, 1894:

“Misha is staying with us since Wednesday. We find him very youthful. He arrived here on the ship “Lazarus” together with the young Sergei Mamontov at 7 o’clock in the morning… We spend most of the time at home, in our company… Misha brought with him about 20 different scenes painted during the recent trip. Some of them are very good. Besides, Misha painted here a fantasy-portrait of Nastya (younger sister – author’s note).”

And here is an excerpt from the following letter, dated May 11:

“Misha is still with us… He painted here two sketches, finished Nastya’s fantasy-portrait and began mine. Now he is sculpting the Demon’s head (broken during transportation from Odessa to Sevastopol – author’s note). In general, he seems to feel out of place, even though we try to make him happier and more peaceful… When Misha will return to Moscow is unclear: apparently he intends to stay some time in Kiev.”

Mikhail Vrubel left Odessa in the second half of May. These six weeks were quite productive. Interestingly, the portrait of Nastya Vrubel joined the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery relatively recently, in the beginning of 2004. Before this, the portrait was kept by the family — the Tretyakov Gallery acquired the portrait from Ksenia Karshova, granddaughter of Anastasia Vrubel on the maternal side.

In a letter to his sister dated December of 1895, Vrubel promises to visit Odessa again in the second half of January or the first half of February of 1895, but those plans did not materialize.

In Odessa, the artist was remembered and appreciated. On April 3rd of 1910, the day of Vrubel’s funeral — he is buried at the Novodevichy Convent in St. Petersburg — the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture held a memorial service for the deceased artist, with Leonid Pasternak in attendance among others. In May, a memorial was also held in Odessa, at the Odessa Cathedral. The initiative came from the wife of the Alexandrovsky partnership sugar factory director, Ekaterina Guleva who was known in the city as a benefactor, was friendly with artists and a painter herself. The memorial service was attended by the city’s major artists. Vrubel’s death was noted by Natan Inber and and Pyotr Nylus — in April, articles dedicated to his memory were published in the “Odessa News.”

Odessites are in luck — the Odessa Fine Arts Museum exhibits some excellent works of Mikhail Vrubel. One of them — “Swamp lights” dated 1890 — always scared me as a child. The work came to the museum in 1926 from the collection of Mikhail Braykevich, as well as another painting — “Valkyrie,” depicting the Princess Maria Tenisheva. There are two drawings in the museum collection: “Y. V. Tarnovskiy’s family at the card table” of 1887 and “Portrait of an Unknown Lady,” as well as two painted ceramics: “Volkhova” based on Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera “Sadko,” and “Woman in a headdress” previously held in the collection of A. P. Russow.

Yevgeniy Demenok is a writer, journalist, and cultural historian who has authored five books. He is a winner of the Paustovsky’s Municipal Literary Prize for his 2014 book ‘New, on the Burliuks.’ He is a founding organizer of Odessa Intelligentsia Forum and a member of the Presidential Council of the Worldwide Club of Odessans.